A Proposal for an Artists’ Union

9 July 2024By Jay Isaac

In 2020, I made a large-scale painting titled Mural Study for the Future Site of an Artist Union. The title ironically alluded to the fact that the painting was being shown in a commercial gallery, and with an idealistic future outcome, this venue, and perhaps other galleries, might become the site of an artist union. The painting is now housed in the Ivey Business School at Western University in London, Ontario. Students learning the fundamentals of business can view the painting as they leave the cafeteria and wait for the elevator to return to their classes.

The painting was made at a time when COVID-19 was in its beginnings, and I, like so many others, was forced to think in-depth about the working class who, like artists, engage in labour that is oftentimes overlooked and undervalued. All artists have the right to the basic needs of survival—in fact, everyone has the right to the basic needs of survival—but the current systems for working as an artist in Canada are at odds with this principle. The undervaluation of art is perhaps due to the Canadian public’s perception that artists are elitist or that art is a luxury. These perceptions are partly true in that commercial art is created and disseminated as luxury items for the rich, and increasingly, many of the participants in the production of art come from upper-middle-class backgrounds. However, these public perceptions do not take into account the majority of artists working in Canada: those who are labourers and need to work jobs outside of their primary art practice to sustain themselves financially.

Many people who work full-time in automobile factories, corporate pharmacies, or provincial liquor stores have some of the benefits that they deserve as labourers because there are unions in place that oversee these workers’ rights. They might receive benefits for dental work, prescriptions, and other health services. There are rules about how and when they can be let go, their working hours, safe working conditions, and the right to not be harassed by colleagues or bosses. As a class of workers, artists have none of these established rights or benefits, mainly because there is no unified artists’ union. An artist could have made a show for a reputable gallery in a mold-filled apartment while working 16-hour days to meet a deadline. As of this moment in Canada, there is no comprehensive oversight of working conditions for artists, but there are a few organizations who are attempting to set some standards.

To start, Canadian Artist Representation/Le Front Des Artistes Canadiens (CARFAC) was established in 1968 and exists for all visual artists presenting work within the public realm in Canada to ensure they are paid fees for exhibitions and reproductions of their work.1 CARFAC ensures that artists are paid regardless of whether their work has market interest, unlike in the commercial realm where artists are only paid if a piece of art sells. Even though there is a crossover between artists who exhibit at Artist-Run Centres (ARCs) and commercial galleries, ARCs provide more opportunities to exhibit for artists who are from culturally diverse backgrounds, or who have more theory-based practices that are less commercially motivated. Similar to commercial galleries, ARCs are free and open to the public. Although the fees paid for exhibiting or reproducing images of works are a necessity for artists working in Canada, the current amounts paid are by no means sufficient for a living wage.2 For most artists in Canada, an ARC artist fee is about as frequent as an artwork sale.

There are no universally agreed on codes of conduct or fee schedules for artists working within the commercial realm, as it is assumed that the privilege of being within the commercial system is a reward in and of itself. The commercial gallery system is essentially set up like a pyramid scheme. A group of lower-paid artists make money as a unit to pay the person at top of the pyramid or hierarchy, the dealer. When this structure is examined, what is in place is a system of numbers and odds. If a gallery has a roster of 20 artists who all create consistently, each with numerous works available for sale, then the dealer’s odds of making a sale, and thus profiting, are many times higher than any of their artists.

Due to the extreme opacity of business transactions in the commercial realm, there is little to no statistical information about art dealer incomes in Canada. Conversely, there have been several studies looking at artists’ average annual incomes working in Canada.3 As an artist who has worked for almost 30 years in the commercial system, I also know firsthand from my own experience, and that of my peers, that artwork sales are scant, meaning that few artists working in Canada are fully supported by artwork sales alone. Commercial galleries can exist, thriving economy or not, because there is a base of workers who produce objects for potential sale at all times. The system is set up so that if a few of the artists on a gallery roster are commercially successful, the dealer can continue to operate. Gallery artists who are making no sales, however, must find their own ways to generate income. The system, therefore, favours the dealer over the artist.

Another example of disparity as it pertains to artists is the exaggerated difference between the incomes of visual artists and those of the CEOs of art institutions. Stephan Jost, the current CEO of the Art Gallery of Ontario, made $404,004 in 2023.4 Jost is the highest paid employee at the AGO, but it should also be noted that 68 individuals working at the AGO are on the Ontario Sunshine List and make over $100,000 a year. The median individual income of artists in Canada is $24,300.5 In this way, it seems accurate and fair to compare Stephen Jost to Galen Weston Jr. (the President of Loblaws), and artists to workers at a Loblaws grocery store. There is no rational argument for someone to be making that much money as a CEO when the core producers of that institution, the artists, are struggling to survive.

***

These arguments aside, another important factor that is often not considered in the hierarchical capitalist system is the symbiotic relationships where artists who work within a community are influenced by each other as they develop. As some “rise” to success, others do not. Success, as it is interpreted through the capitalist lens, does not take into consideration the numerous and immeasurable factors that may hinder an artist’s development. I am not the first to point out that there are factors beyond “talent” that lead to success, such as not having the burden of art school debt, alongside benefits such as affluent parents, stable housing, or being neuro-typical and able-bodied. Is it possible to step outside of the typified parameters of success and acknowledge the worth of all serious artists? I am not suggesting all art is good; I am, however, saying that the neoliberal meritocracy that has been upheld might not be as fair as we have been led to believe.

This system is flawed because numerous artists within the system contribute ideas and experiments to the whole, which are then refined by more astute practitioners. This is just how the system works, we all say. But if we are discussing labour value, then we need to acknowledge all forms of labour that contribute to the whole, the whole being a community at a given time in a given place. The less visible artist practitioners could be equated to essential workers. We know from the COVID-19 pandemic that essential workers are the people that make the world run smoothly. If they do not go to work, then society as we know it cannot function.

Diverse positions are important to the fabric of the collective and need to be valued as such. There needs to be a move away from thoughtless, constant growth and a shift towards contentment and sustainability in all aspects of life, including artistic creation. If respect can be attained by all levels of players within a system, then the system has a greater opportunity to be equitable and thrive. It becomes sustainable and has longevity.

***

One of the core principles of a union is job security. A unionized worker knows that their job cannot be taken away on a whim and that it could employ them through the entirety of their lives. Artists also deserve this sense of security and permanence. Many aspects of the artist’s life are insecure: there are no bi-weekly paycheques, there are no benefits, there is no job security. As a self-employed freelancer, the artist is responsible for generating income without an established framework in place.

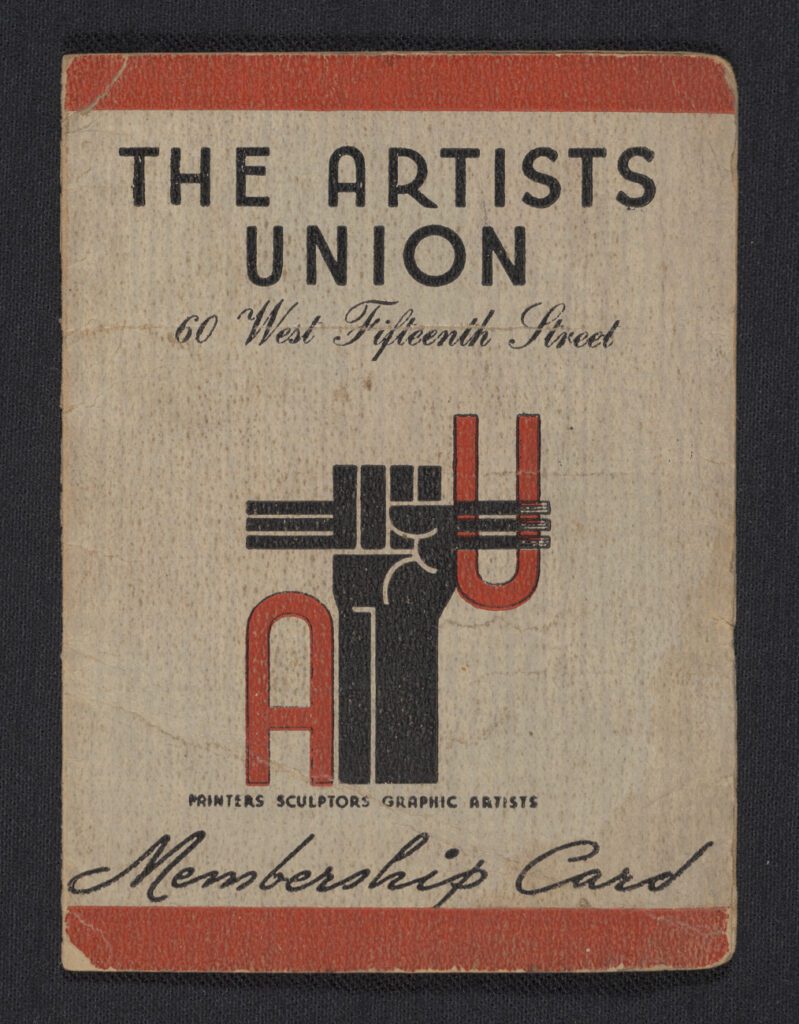

The history of artist unions is limited. The first documented attempt at artists unionizing was in 1933 by a group of artists in New York during the Great Depression. Initially called the Emergency Work Bureau Artists Group, they eventually changed their name to the Unemployed Artists Group and then finally to the Artists Union.6 The union was formed to assist unemployed artists in finding work and was influential in the establishment of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided artists with well-paid jobs creating murals and public art throughout the US. They demanded state funding for artists in need and participated in protests supporting other workers’ unions and left-wing organizations. After five years of activity and attempts to secure ongoing support for artists, the union ultimately fizzled out and merged with the American Artists’ Congress in 1942, creating the Artists League of America.7

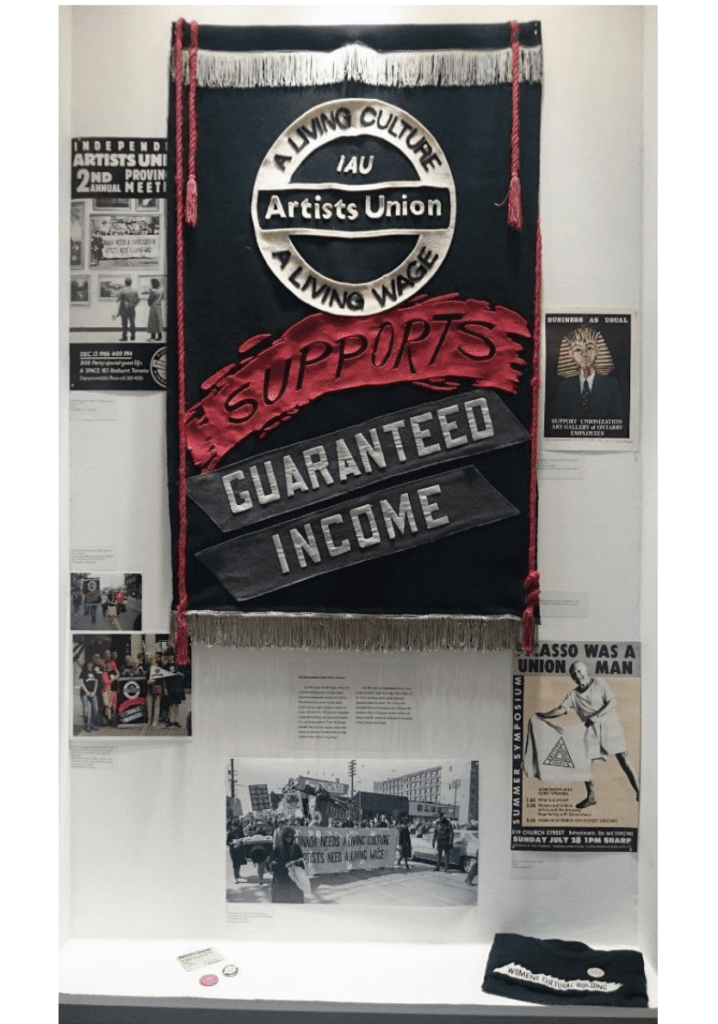

In Canada, artists Karl Beveridge and Carole Condé created the Independent Artists’ Union (IAU), whose essential mandate was encapsulated in their slogan “a living culture, a living wage.”8 The IAU was primarily organized in Ontario in the 1980s and at its peak had 1,000 members. In a 2013 interview with the Canadian Journal of Communication, Condé states:

The IAU lasted three or four years. Toronto was its centre, and then Hamilton, Thunder Bay, Kingston, Windsor, Sudbury, and Ottawa got organized, too. One thing we were fighting for was a living wage. It was then, like it is now, difficult for artists to make a living. Most of us were anti-dealer. And many of us were earning money by teaching. Few could actually work as an artist full time.9

Among many of their propositions for further pay equity for artists, the IAU proposed that rather than a competition-based granting model, money should be pooled and distributed into a wage, which would be the equivalent of minimum wage for working artists in Canada. The main issue that they encountered in establishing the union was that there was no constant employer, in the way that a corporation or a company is a constant employer. It was argued that the Canada Council could be considered a constant employer, as well as museums. Despite its efforts, the IAU eventually disbanded because the organization was run by a group of unpaid volunteers.

Current initiatives do exist to give artists more support in Canada. One such is the Al and Malka Green Artists’ Health Centre in Toronto, a medical centre dedicated solely to providing health care services to artists. Their website states: “The centre’s team specializes in addressing the specific healthcare needs of artists providing a holistic approach to health within an evidence-based framework.”10 Services are subsidized for artists according to their financial status.

In British Columbia, the Arts and Cultural Workers Union (ACWU) was formally granted a union charter in 2020. They are affiliated with IATSE and have stated that they have long-term goals to create benefits for arts workers and administrators in BC and eventually across Canada. “The ACWU was formed to work in solidarity with the broader labour movement to address the common issues of income precarity, exploitation, and job insecurity in the arts and cultural sector.”11

Another initiative is the implementation of the Artist Resale Right (ARR). The ARR proposes that any artwork sold in the secondary market must give a percentage back to the artist who created the work.12 ARR payments are more of a symbolic gesture to the artist acknowledging the new placement of their work, rather than making any significant impact on anyone’s financial well-being. However, for an artist to have a sustainable career, there needs to be a myriad of income sources.

Universal basic income (UBI), or the idea that the government gives its citizens a livable wage simply for being citizens, has been implemented experimentally in several countries and states to varying degrees of success. Finland, for example, has conducted the most comprehensive study determining the effects of implementing a UBI. To date, it is the only country that has completed a nationwide randomized control trial using diverse research methods to accurately study the effects on its citizens who received the monthly income without conditions.13 The results of the two-year study were manifold, but the most distinctive result was the boost to the overall well-being of the participants: “People receiving the basic income reported better health and lower levels of stress, depression, sadness, and loneliness—all major determinants of happiness.”14

In Canada, we have a competition-based granting system that is invaluable but also flawed. With the Canada Council for the Arts, as well as in provincial granting systems, there is no opportunity to note financial status as a potentially marginalizing factor for artists applying for project funding. In addition to the regional and essential cultural diversity statistics they currently take into consideration, income disparity should be a primary concern for granting bodies.15

As previously mentioned, the core reason the IAU was not successful in the long term was that there needed to be a constant employer for a union to have relevance. I propose that the network of collectors, dealers, and arts administrators who rely on artists for their activities is the equivalent of a constant employer. The collector acquires the artist’s work, the dealer typically receives 50% when a work sells, and the arts administrator has a job because artists exist and create. Considering this, to successfully organize a visual artist union in Canada, there needs to be a tax or a fee collected by an organized group of artists taken from each party who benefits from artists’ work who are not artists. A percentage from each sale and each paycheque would be collected to assist in paying a living wage to artists. If someone enjoys having art on their walls and values the job they have because of artists, then it only makes sense that they contribute financially to the artist’s well-being. There are hundreds of cultural workers in Canada with steady paycheques who rely on artists’ work to make their living. Without artists, these jobs would not exist.

Additionally, I propose that every commercial gallery in Canada unionize. Within this proposed unionized commercial gallery setting, each artist would be given a basic income from the gallerist that they work with as they are essentially the constant employer. The amount of the basic income would be decided by a group of unionized artists in each gallery. There would be mediators and there would be bargaining. If bargaining fails, then the artists could go on strike until their demands are met or are renegotiated. Unfortunately, the general public in Canada does not care if artists go on strike. A dealer, however, does care if their artists go on strike, because their livelihood depends on it. A dealer has chosen to work with an artist and each of those artists were desirable at some point. They should therefore have rights and the continued, guaranteed means in which to survive and do their job with dignity.

The essential premise of this proposal is that there needs to be a multi-faceted approach to creating financially sustainable conditions for artists. To answer the question of “how” this can happen, here are the steps I propose:

- A fee paid to the national artist union by anyone who benefits financially from artists’ work. A percentage of sales and wages will be garnered and distributed to maintain the union and pay out wages to artists.

- Individual unions within each gallery entity. All commercial and non-profit galleries will be unionized.

- Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all artists working in Canada.

- Implementation of the Artist Resale Right (ARR).

If artists have organized support, then they can be assured that even in times of financial hardship, low interest in their work, or emergencies, they are not disposable and will have the means to survive and thrive creatively. I believe that everyone would benefit, including dealers. Artists would have more time to focus on their practice and create better quality work, creating a scenario where making sales could be easier for the dealer. High-functioning artists also means creative projects consistently being available to the public.

Being an artist oftentimes means working alone. If artists were to unionize, then the opportunity would exist to create change as a voting group. The proposed artist union could protest in solidarity with adjacent justice causes, add presence to boycotts and rallies, and affect more change as a group than as a fractured, amorphous entity.

I have seen countless artists in financial despair, ongoing for years and sometimes decades. I have witnessed mental breakdowns, public humiliations, callouts, cancellations, suicides, hospitalizations, overdoses, evictions, homelessness, alcoholism, and drug addictions, all related to the difficulties of being a cultural labourer in Canada. I know of artists not getting paid by their dealers many, many times.

I propose that we no longer rely on large art institutions, granting bodies, or galleries to ascertain that we are successful or allowed to speak on the issues we care about. Collectively, we need to organize significantly better than we are currently. I have seen how the system creates competition between artists, who are all vying for limited exposure and resources. We need to support each other and establish a system of governance for us while no longer accepting the narrative that what we do is non-essential. As a collective of intelligent and passionate people, the community of visual artists has the potential to be a force of positive change, self-determination, and empowerment.

- “About CARFAC,” CARFAC, https://www.carfac.ca/about/#:~:text=CARFAC%20was%20established%20by%20artists,in%20profits%20from%20their%20work.

- As per the CARFAC 2024 fee schedule, the minimum recommended rate for a solo exhibition is $2,380. See the CARFAC minimum recommended fee schedule here: https://carfac-raav.ca/2024-en/.

- “A Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada in 2016,” Canada Council for the Arts, https://canadacouncil.ca/research/research-library/2019/03/a-statistical-profile-of-artists-in-canada-in-2016.

- Ontario Sunshine List 2024, https://www.sunshineliststats.com/?page=1&provinceid=9&year=2024&n=artgalleryofontario.

- Hill Strategies, “A Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada in 2016,” https://hillstrategies.com/resource/statistical-profile-of-artists-in-canada-in-2016/.

- Gerald M. Munroe, “The Artists Union of New York,” Art Journal, Volume 32, Issue 1, 1972, https://www.jstor.org/stable/775601.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artists_Union

- “The Art of Collective Bargaining: An interview with Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge,” Canadian Journal of Communication, Volume 40, Issue 2, May 2015, https://cjc.utpjournals.press/doi/full/10.22230/cjc.2015v40n2a2994.

- Ibid.

- https://www.artistshealthcentre.ca/displayPage.php?page=What%20We%20Do

- See the Arts and Cultural Workers Union website, https://artsandculturalworkersunion.wildapricot.org/About-ACWU.

- I have been a proponent of this for many years and the former business I ran, Peter Estey Fine Art, was the first and only auction house in Canada to pay 5% of the sale price on secondary market works to any living artist in Canada. See: https://www.carfac.ca/campaigns/artists-resale-right/ and https://news.artnet.com/market/auction-house-resale-royalties-1718388.

- McKinsey and Company, “An Experiment to Inform Universal Basic Income,” September 15, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/an-experiment-to-inform-universal-basic-income.

- Ibid.

- The median individual income of Canada’s artists is $24,300, or 44% less than all Canadian workers ($43,500). The main component of total income, for most workers, is employment income (including wages, salaries, and self-employment earnings). A typical artist has employment income of $17,300, a figure that is 56% lower than the median of all workers ($39,000). See “A Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada in 2016,” Canada Council for the Arts, https://canadacouncil.ca/research/research-library/2019/03/a-statistical-profile-of-artists-in-canada-in-2016.

Feature Image: Mural Study for the Future Site of an Artist Union, 2020 by Jay Isaac. Photo courtesy of the artist.