Because Every Day is Filled with Unmemorable Time: A Conversation with Hyang Cho

14 December 2023By sophia bartholomew

At sunset, in the calm before a torrential downpour, I spoke with artist Hyang Cho inside the makeshift studio she’s set up inside her garage in Guelph, ON. We talked about her most recent exhibition, Certain Things from Uncertain Moments, which ran from January 14 – March 11, 2023 at YYZ Artists’ Outlet, and reflected on using time as material when creating sculptural work, the relationship between time and boredom, and the near-geologic sedimentation of her varied material accumulations. She walked me through the differentiation she makes between “collecting” and “saving,” and why she always “pauses” her projects rather than “ending” them. We discussed the subtle variations in mass produced objects like glass jars and plastic bags, and whether or not materials can ever truly be transformed. In Cho’s process, a book always remains a book, even after it’s been torn up, mixed with glue, and turned into a rock-like lump of papier mâché—and through our conversation, she also convinced me that sometimes tearing a book apart is more pleasurable than reading.

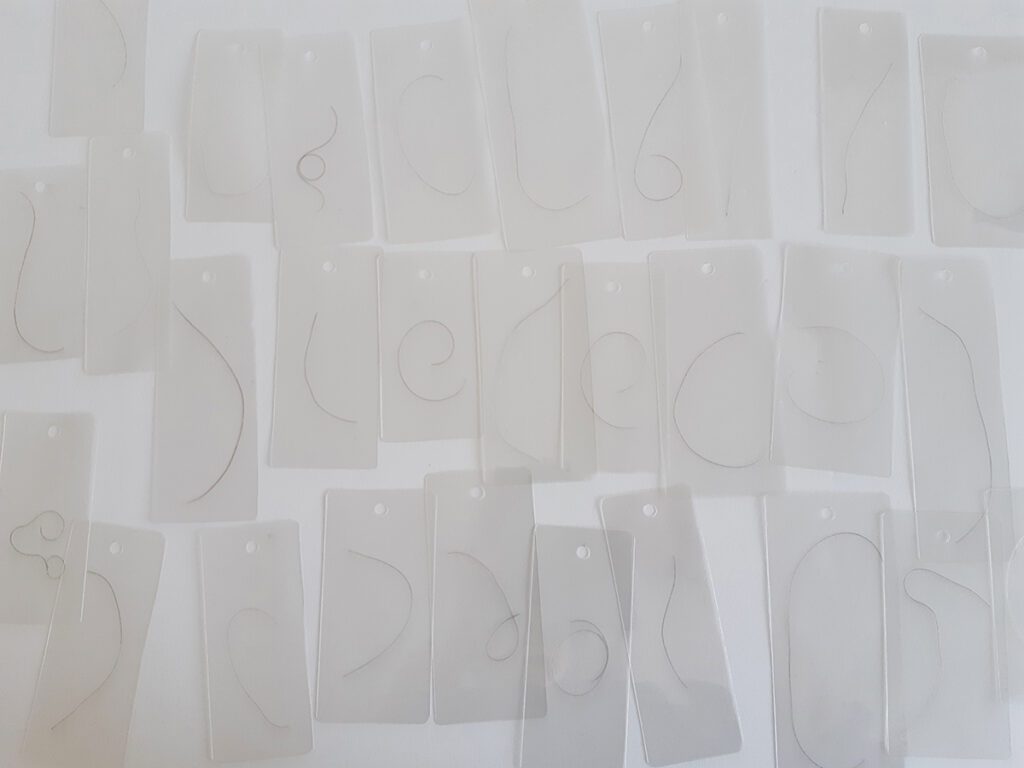

sophia barthomew: I wanted to start by showing you something—I noticed, when I was taking receipts out of my wallet the other day—I’ve been keeping this [a small artist multiple: a clear rectangle of laminated plastic, containing a single hair] in my wallet, ever since I picked it up at your exhibition at YYZ in Toronto earlier this year.

Hyang Cho: Great! Thanks for taking one.

sb: Maybe that’s a good place to start? Maybe you could tell me a bit about this work (Hairs, 2020–ongoing)?

HC: I don’t know, I just noticed the hairs on the floor. Probably because of the pandemic. I stayed home more, doing nothing, and wondered: What’s going on? What should I do? What’s going on outside? I stared at the floor, and there were my hairs. I think there were always hairs on the floor, but I started to notice them because of the circumstances. I started to pick them up. Usually I just throw them away, but instead I kept them. And… it’s not really about collecting. I always say: I don’t collect things. Sometimes I save things instead of throwing them away.

sb: What’s the difference for you? Between collecting and saving?

HC: Collecting… it’s more precious. If I’m collecting I should have an intention to acquire things that I do not have. Saving, on the other hand, is about holding on to things that I already happen to have. I save many things: stray hairs, the bugs that I kill (Bugs, 2020–ongoing), and the bones from the animals that I eat (Bones, 2020–ongoing)… I’m not collecting them, I’m just not throwing them away.

sb: Oh yeah, interesting. I’ve never made that differentiation before, but part of what resonated for me with the work in your exhibition were these accumulations of small, everyday things. Many of them were materials that would normally end up in the garbage. You had this pile of apple seeds, shown alongside small plants grown from the seeds, and photographs of seedlings that had since died. A couple of years ago, I also started saving lemon seeds, and then apple seeds. And hairs—during the pandemic, I also really noticed the hair. As I swept the floors I started making digital scans of the hairs. My hair was longer, it would sort of get tangled and make these drawings…

HC: Yes, I think because of the pandemic more people are collecting hair. I also saw on YouTube, there are also so many people growing things after saving the seeds from the food they’re eating.

sb: Did this practice of saving things start before the pandemic?

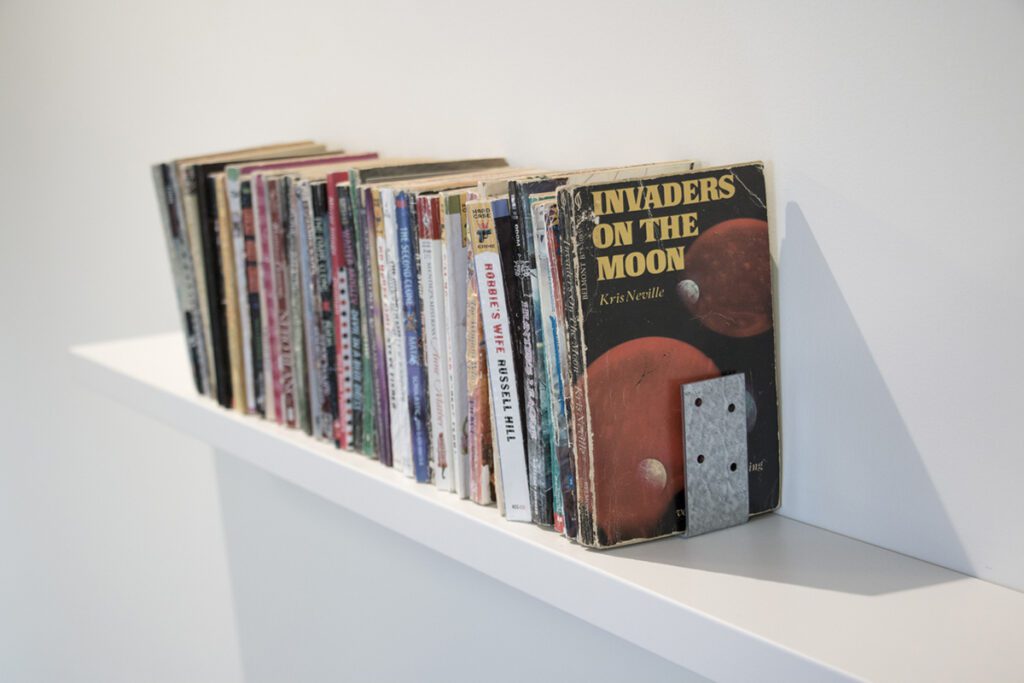

HC: Yes, before the hair, I was already collecting and saving. I saved glass jars from the mass-produced food products that I consumed (Jars, 2015) and buttons from unwanted garments. Actually, it was my mother who saved the buttons, and I used them for making a work (Buttons, 2015). I also picked up discarded paperback books from the Guelph Public Library years ago. I didn’t have any intention of reading them, but I was interested in the titles and the covers. I bought them and I glued all of the pages together, so… it’s still a book (Books 1, 2010).

sb: It’s just not functional to read anymore.

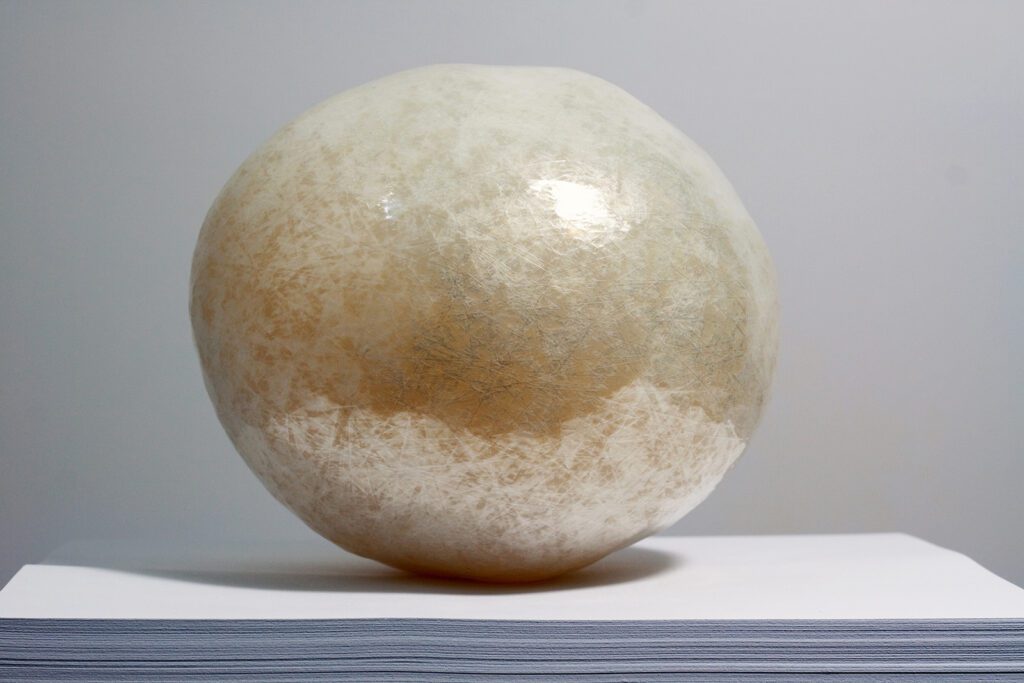

HC: Yeah, exactly. I also saved all of the flyers that were thrown at my door for a year. I made a huge ball (Agglomerate, 2018)—papier maché—out of all of them.

sb: The form of the ball is a recurring shape in your work. Wouldn’t you say so? You have a transcendently beautiful ball of tape…

HC: Yeah, I have a ball of tape (5.6879264, 2015). I also have a ball made from typewriter ribbons (It’s (missing), 2013), and a ball made from the broken glass jars (Sphered, 2016).

sb: That spherical form… When you’re saving materials, is that just the easiest form to make?

HC: I don’t have any philosophical reasons for using the ball form. Like you said, it’s just a shape that turned out. With the tape—I didn’t intend to make a ball, I just wrapped the tape again and again and it became ball-shaped. With the flyer thing too; the way it was just accumulating… I didn’t want a specific shape out of it, so it became a ball.

sb: Yeah, that is different. In your exhibition at YYZ, you made pulp from your personal collection of paperback books and made them into these rock-like forms (Lumps, 2023) using papier maché, right? That seems to me to be a more specific form that you’ve chosen.

HC: No… It’s also a thing without form, or without a specific form. I didn’t want to make another ball, but at the same time I didn’t want to make a specifically shaped object, so I squished it. It’s still intentional, but at the same time it’s an unintentional shape. I didn’t want them to resemble rocks, but I realized that rocks are these sort of shapeless shapes that happen to be like that.

sb: The rocks were really striking. They looked like real piles of rocks when we came into the gallery, but as you got closer, you could see some surviving words from the novels on the surface. Is that interesting to you? That they don’t seem to be made from what they’re made from? It creates an unexpected discovery for the people who encounter them.

HC: I don’t know. For me, those books (Lumps, 2023) are still books. I didn’t know that they were going to really look like rocks. I did know, however, that they were all going to look a little bit different from one another, since all of those books have different textures. This is especially true with paperbacks, because the paper deteriorates over time. When I do the papier maché, when I tear the papers, some books are really tough. I hate Penguin books because they use pretty good paper. It’s hard to turn them into papier maché.

sb: The crappy paper is much better.

HC: [Laughs] Yes.

sb: As I’ve saved my own “waste” materials, I’ve found that you become attuned to those subtle differences in quality as soon as you start negotiating with the material.

HC: When I see mass produced things—with books too—the sizes are all different. I thought there should be a standard size for books, but there isn’t. All paperbacks are a different size. Same with those mass produced glass bottles (Jars, 2015).

sb: And when you were making the rock-like shapes from these books, was it just the pages? Or do you use the covers as well?

HC: No, I didn’t use the covers because covers are tough, and some are coated with vinyl. I’ve saved all of the covers for… I don’t know what project.

sb: The “rocks” might be an accidental form, but there is this relationship with geology insofar as there’s this accumulation, a sedimentation. It seems like a lot of how you’re working is collecting things—sorry, saving things over a long period of time. And this mass building-up over time feels like an important aspect of the work.

HC: I guess so. I don’t know why I like a lot of things. I mean, the quantity is really important. Sometimes it shows time.

sb: I don’t know if you would think about it this way, but these things seem to be involved in bearing witness. You’re witnessing the materials, honouring them in a way, just by not just discarding them. But then they’re also witness to you, and witness to time—to the passage of time more specifically—and when you gather them all together, they represent this passage of time. In your artist statement, you talked about boredom. I wonder—is there a relationship between time and boredom? I mean, is most of our time kind of…

HC: Boring?

sb: Yeah.

HC: I mean, I like the exciting moments too, but I noticed that when I think back, I only remember the exciting events. Like the day I came to Canada. Something like that. And I started to wonder, what was happening in-between those exciting moments? I guess every day is filled with this kind of unmemorable time. Like the unmemorable books from the library, and the hairs on the floor, and the bugs that I killed.

sb: One way that I’ve thought about it is like negative and positive space in a drawing. The memorable things are like the positive space, but the negative space is also part of the picture—it’s palpable if you pay attention to it. The things around the things are usually not given much attention, but it’s these unmemorable “things,” like eating apples, or recycling flyers—that’s actually how the majority of our time is spent.

HC: This time forms my everyday, and it forms me, I guess. I don’t remember it, but it changes me.

sb: It literally forms you! The apples and the animals become part of your body, and your body is shedding hairs as your cells are changing over.

HC: For the hair, I wanted to give away some part of my body. [Laughs] It’s kind of gross. If I find someone else’s hair on my bag or something, it’s gross. But I liked the idea of giving a part of the body to others.

sb: Part of the exhibition at YYZ was that if people took one of your laminated hairs, they were also invited to leave a hair or hairs behind, in a bowl, I think?

HC: Yeah, and I saved them. I want to do something with them in the future.

sb: And there’s something different that happens because you laminated your hairs. They become sort of sterilized.

HC: Well, it’s really two different things put together (the laminator sheets and the hair). I have a laminating machine, and I was thinking: What could I laminate? Hairs were really unnoticeable when I laminated them, and I thought maybe hairs are the best thing I could laminate. I didn’t have the intention to sterilize them.

sb: It’s also practical. Hairs are so ephemeral, hard to grasp. Fixing the hair between laminating sheets gives it a shape; makes them solid.

HC: So I can use it as a bookmark… I like the idea of the work being functional in some way.

sb: There’s something nice about an artwork that’s a part of people’s day-to-day lives. I wonder, is there a connection between that and the idea of unmemorable time that we were just talking about? Since visiting the exhibition, this laminated hair “bookmark” lives inside of my wallet. It’s now embedded in my life. It’s there with me when I’m at the store, buying groceries, or when I’m at the doctor’s office, when I’m getting ID-ed, when I’m depositing a cheque at the bank. It’s now participating in a lot of unmemorable moments in my life, in between the more exciting and memorable things.

HC: For me, a bookmark is used to mark the moment that I stop reading. It’s not that I use it to find passages that I want to come back to. A bookmark is the moment when I have something else to do, so I have to stop reading. Also, I hardly ever finish a book. I have twelve different books going at once, and I rarely finish any of them.

sb: I have this problem too. [Laughs] Sometimes the book is sitting there for years and I’ve only gotten as far as the bookmark. Can you tell me a bit more about how that exhibition at YYZ came together?

HC: I applied for the exhibition at YYZ many years ago and then sort of forgot about it. I heard about the exhibition just before the pandemic, like in February 2020. They scheduled the exhibition for 2023, and in those years in-between a lot of things happened. The year before the pandemic, I hadn’t been making things as an artist for a while. So when the time came, I didn’t know what to do for the exhibition really, but I knew that I didn’t want to show old things. Then the pandemic started and I forgot about the exhibition again. I didn’t plan for the future. The future looked so obscure.

sb: Yeah, everything was very uncertain for a long time.

HC: So I stayed home, like everybody else. I was picking up the hairs from the floor. I was eating apples.

sb: Those materials in the exhibition were all things saved from your time at home during the pandemic? Like a kind of index?

HC: Yes, they are all from the three years before the exhibition. Cooking chickens, eating them, I just so happened to save all those things, I don’t know why. I’m still saving the hairs and saving the bugs that I killed, lots of mosquitos nowadays. I’ve stopped eating meat with bones in it because I kind of got tired of cleaning the bones. I got tired of those smells too.

sb: Okay, so instead of quitting the project, you’ve changed your diet?

HC: [Laughs] Yes. It’s not like I start from here [marking a point in space with one hand] and then here [marking a point in space with the other hand] it’s finished. It’s not like that. I never finish my work. I can’t say that I’m finished with those rock-like books. I can’t say that I’m going to continue with them either.

sb: It’s open ended. It’s like a bookmark: like you might finish the book, or you might not.

HC: Yes, probably I’m not going to make anymore, but I don’t want to say that it’s a finished project. I just say that it’s paused. I try to leave some possibilities open.

sb: Why is that important?

HC: I don’t know when to finish! For a specific project, like the flyer ball (Agglomerate, 2018), I felt done with it when I wasn’t able to handle it anymore. It became too heavy for me to handle, so I had to stop.

sb: It has a physical limit. The work tells you the limit. And then it’s over and you know it’s over.

HC: Sometimes I’m tired of it too. Sometimes I have other work that I want to make. In that case I just…

sb: Pause?

HC: [Laughs] Yes, pause. I’m still saving those seeds, but I have stopped planting them. I stopped trying to sprout them too because I have a lot of plants right now.

sb: I bet. Apple seeds are interesting because apples aren’t usually propagated through planting seeds. Usually it’s done through grafting. The seed might produce a tree that produces some kind of apple, but there’s not a clear relationship between the apple it came from and the apple tree it becomes. It will probably produce a crab apple.

HC: Probably inedible.

sb: Does saving all of these things ever become a storage problem for you?

HC: No, hairs don’t need a lot of space. And I already had a lot of paperbacks, so it was good for me to process them. I really like the feeling of ripping those papers instead of reading them. I know that things are accumulating, but I like to think that I’m okay with it. Sometimes I throw them away too. It’s not a good thing to say, but sometimes I’m relieved when my plants are dead. I don’t feel good about it, but I’m not good at growing things. The plants that were in the exhibition were the survivors. I started to take pictures of the plants because I was scared that they would all die and I wouldn’t have anything for the exhibition. Probably half of them died in the process.

sb: In the act of saving things, there’s this kind of energy deposit—the materials are imbued with your time and your attention. You’re saving things, and as a result, you’re transforming them into something different than what they were. Do you ever think about your process as an act of transformation? One thing becoming something else?

HC: It’s not that one thing is becoming something else. For me tape is tape. Tape is meant to stick to things. I just follow its nature. The tape works just happened, they transformed into something else, but also not completely. With the book-rocks too, they’re still books. I tried to leave them as they are.

sb: It seems like it’s about listening to the logic of the material. Like with the tape, this is the thing that tape does, it sticks. You’re following the logic of that material.

HC: Yes, sometimes. Hmm. You see the flyer balls and the paper rocks? The flyers didn’t have an individual character, so they became one mass, but the books couldn’t do that. Each book has a different character. Somehow for me it’s obvious what to do with them.

sb: I’m seeing a connection between glue as a material and the stickiness of the mundane, boring acts that you’re paying attention to. I don’t know if that makes sense, but I’m making a connection between glue and what you’re describing as unmemorable time, which also has this glue effect. It gives continuity—these rituals, these small acts—even though they’re kind of invisible, they’re actually what holds a life together.

HC: Yeah. That’s very interesting. I’ve never thought about glue, or the stickiness of things in that way.

sb: Does your attention—in other words your time and your energy—does that become part of the substance of the work? Like that becomes somehow deposited in the work?

HC: Maybe. I put a lot of time into my work. Time is the only thing I have a lot of. I think the work represents materialized time. I am only able to grasp the present time through these things that I make. The artworks then become evidence of passing time, accumulated time—time becomes something I can touch.

Certain Things from Uncertain Moments by Hyang Cho ran from January 14 – March 11, 2023 at YYZ Artists’ Outlet in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: 5.6879264, 2015 by Hyang Cho. Photo courtesy of the artist.