Climate Futures and Spectral Atmospheres in Tracy Peters’ Bog Sensing

16 March 2024By Lindsey french

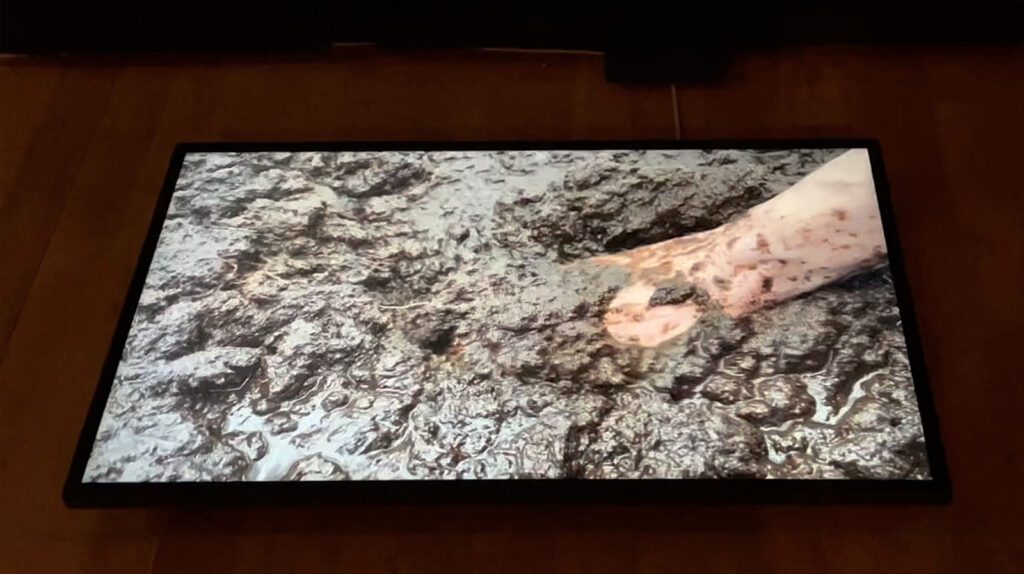

“The sound is incredible. I knew I might never hear anything like that again.” As artist Tracy Peters describes this to me, I try to imagine the squelch of snowshoes pressing into a dense mat of waterlogged Sphagnum moss. The artist is telling me about her recent research trip to Store Mosse National Park, the largest protected bog in Sweden, where she spent three days during the autumn of 2022 walking among acid-loving plants, submerging film and photo paper below the wet surface, and making audio and video recordings. She sends me a video from the resulting exhibition in Stockholm: it depicts her hand reaching into wet soil, submerged, then gliding through the peat while mismatched audio of footsteps sonically tell me more about the surface of this landscape than what I can visibly see.

I am speaking with Peters about her practice after visiting Bog Sensing, her site-specific outdoor work which accompanied an indoor exhibit Subconscious Terrain at the Estevan Art Gallery and Museum in Saskatchewan. This work is part of an overarching project investigating the vulnerable sphagnum moss, organisms which are vital to the discussion of climate futures for their role as carbon sinks, which remove carbon from the atmosphere and thus contribute to lower atmospheric greenhouse gasses.

Bog Sensing (2022) consists of four plinths with acrylic vitrines lined with sculptural and water-altered prints of moss, carefully positioned to be transformed via sunlight by day, and artificial light by night. The plinths are placed at public edges—a dog park on the way out of town, alongside a river, at the roadsides within a provincial park campground—punctuating these social spaces of Woodlawn Park with illuminated images of plants that also exist on the edges of life and death. Each plinth is lined with prints of sphagnum moss that have been soaked in water and then sculpted to create a textured form when dried. The outer faces of the plinth display dead sphagnum mosses, while the inside is printed with living moss, and the north face of each plinth is left clear so that the viewer can peer inside to view the sun-filtered prints throughout the day. As night falls, a solar-powered light illuminates the prints from the inside, visible at a distance throughout the park and drawing the senses to these glowing images at the edges of the river, activated most intensely during the transition from day to night.

As an outdoor piece, locating the work is part of the experience. I am reminded of trips to visit Land Art works of the American West. I look at maps; I scan the landscape; I look for clues. In this process, I am as attuned to the landscape as I am to the artistic intervention. Peters’ work leads me to sites of leisure within this southern Saskatchewan city shaped by industries of extraction. The last two plinths are fully inside the provincial park. One of Peters’ plinths is integrated into a war memorial, the other set amongst campsites near a wetland. In the heat of the summer day, I only notice the plinth because I am looking for it, but at nightfall the piece glows into visibility, the fragile warped images of sphagnum moss gently radiating these images of the dead and the living behind the acrylic casing. The contrast is jarring, and these spectral, half-alive organisms glowing among these scenes of summer recreation calls to mind the words of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, who writes about ghosts and freedom in her work with Hmong mushroom pickers. She, too, is thinking about climate futures, when she writes, “Freedom is the negotiation of ghosts on a haunted landscape; it does not exorcize the haunting but works to survive and negotiate it with flair.”1

Down the road from Peters’ plinths, a coal plant combusts fossil fuels and supplies the grid with power that charges my camera battery. Like the sphagnum moss, the power plant is a crucial player in the carbon cycle: carbon is temporarily captured at this site of fossil fuel combustion, later pumped underground in nearby oil fields for the dual and somewhat contradictory purposes of both storing carbon and increasing oil production. Peters describes bogs as landscapes that exist between life and death. Sphagnum moss dies and the living moss grows atop of it. Bogs are major carbon sinks with deep layers of fermenting dead sphagnum buried beneath the living for centuries or millennia. The mosses filter water, prevent floods, droughts and forest fires, and sink carbon on a planet where carbon is released into the atmosphere at unprecedented rates. If drained, a bog can switch to an atmospheric disaster, becoming a forest fire and releasing centuries of stored carbon back into the atmosphere. I imagine these landscapes as haunted with the ghosts of carbon past, which, if released, would make a hot August day in southern Saskatchewan even hotter. If the ghosts of carbon cannot be exorcized, how do we negotiate the spectral presence of atmospheric futures?

At the Estevan Art Gallery I visited Subconscious Terrain (2022), the partner of Bog Sensing. Inside the cooled gallery, dozens of textiles depicting enlarged, layered and detailed prints of sphagnum mosses hang at head height from the ceiling with thin, tenderly sewn pieces of fishing wire. Often, we are asked to imagine that fishing line and other installation apparati are invisible, but here, they become woven into the work as stitch and as glare against the matte surface of the textiles. It reflects the light back at me but also makes me aware of the infrastructure of the gallery itself, the insided-ness of this gallery space with its track lighting and air-conditioning gently moving these swaying objects, attached to the ceiling and sewn delicately with its own attachments. The enlarged portraits solemnly memorialize these sphagnum moss, and I am left to wonder about my own position as I drift among them. On that summer day, I was thirsty, and the hanging matte images of sogginess and moisture felt so far away. As I walked through the forms and they blew away from me, I had the feeling that I actually was the ghost—a settler moving through a landscape and its future without the pleasure of sensation. In that moment, I was reminded of the importance of negotiation with the landscape itself. Although bogs may be vulnerable, they are also capable of withholding, full of strength, while being protective of themselves.

A few weeks after experiencing Peters’ exhibit, I visited the Spruce-Peatland Responses Under Climatic and Environmental Change (SPRUCE) experiment at the Marcell Experimental Forest, which has long been a place to study peatlands. Located inside a forest, visitors can walk around without interfering with the research or opening the doors. The center is an active one—and the aesthetics are that of research: specialized materials, carefully labeled with notes and shorthand fairly inscrutable to the casual visitor. Above each door, a label indicates the temperatures by which each station was elevated, alongside a small sign with the words, “Welcome to a warmer future.” Peering through the doors, I could read into the relative health of the black spruce and other plants (are they green? Moist? Brittle? What does the future look like?). Though I didn’t feel the heat on my skin, the words above the door and the implied atmospheres of the future were extremely affective and sensorial.

What does it mean to sense a bog? The sponge-like nature of the wet ground is not suitable for careless walking, and so these landscapes are quite remote to many of us. Peters embraces remoteness in her artistic practice, developing intimate relationships with bogs through embodied and sensorial knowing and transposing this knowledge through a close attention to materiality and its display. The solemn installation of memorialized ethereal portraits in Subconscious Terrain provoked a disembodied contemplation, resolved into direct contact with the atmosphere by the complexly situated plinths of Bog Sensing. Considering SPRUCE and Peters’ Bog Sensing plinths side by side, I can’t help but think about the fragility of protection. In one case, the labs imagine possible futures by producing them on a very small scale. In the other, we are confronted by the difficulties of holding onto something so ephemeral against the eroding powers of nature. Peters’ textured prints curl against the humidity of the acrylic plinths, continuing to warp in the exposure of the heat of the summer sun. I look at the images of the moss, but I feel them within a shared atmosphere, shaped by distant peatlands and local coal plant alike. Even with carbon capture systems, coal plants contribute to a future climate unsupportive of many forms of life. To sense a bog alongside a coal plant is to simultaneously feel both the imminence of climate change, and the tenuous capacity for a vibrant and multi-species climate future.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 76.

Subconscious Terrain by Tracy Peters ran from June 9 – August 12, 2022 at Estevan Art Gallery and Museum in Estevan, SK.

Feature Image: To the Core, 2022 by Tracy Peters. From the solo exhibition Entangled Ecologies at AllArtNow in Stockholm, Sweden. Photo courtesy of the artist.