Democracy has Fallen: Howie Tsui at The Power Plant

4 December 2021

By Jacqueline Kok

Democracy is said to be under threat in various countries across the world, such as the United States, Brazil and Venezuela. Political leaders like Trump, Bolsonaro and Maduro have been heavily scrutinized for their divisive policies that have caused political unrest. In Hong Kong, the people face a similar situation: protesters routinely occupy the streets, brawling with riot police. They fight against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the enforcement of laws and security measures that go against liberal democracy. To outsiders unaware of the turmoil, Hong Kong is unruly and violent. To insiders, Hong Kong is in a “state of exception,” sitting at “a threshold of indeterminacy between democracy and absolutism,”1 where, on the latter end, the CCP holds central authority. Laws become slip- pery when acts of violence that are normally condemned, like police brutality, are passed by the current Pro-Beijing government. In these kinds of fragile moments, where past governing systems could rapidly shatter at the hands of a current ruling government, one can’t help but begin to wonder: would anarchy, even with its implications, provide possible solutions to a jeopardized democracy?

The capacity for opposing ideologies and individuals to coexist in a lawless reality presents itself in Howie Tsui’s solo exhibition, From swelling shadows, we draw our bows at The Power Plant in Toronto. Turning to wuxia, a genre of Chinese fiction describing the adventures of martial artists in ancient China, Tsui illustrates this chaotic space where folks nevertheless cohabitate, possessing the tools and means to fight against authoritative bodies and systems of oppression. As a child of the Chinese diaspora, and a second generation Canadian immigrant, my introduction to wuxia was through Ang Lee’s critically-acclaimed film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). I was both skeptical and enthralled. Flying warriors, a rogue princess, and a treasured sword? It seemed at once impossible and dangerously seductive. Like Lee, Tsui presents an equally alluring narrative. Set in a nihilistic Hong Kong, Tsui’s works push the potential to realize a freedom that is hidden in the interstices of government, in its various forms.

Tsui’s subversive pieces are textured through their intent and content. Anchored in the sociopolitical realities of the former Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, his works ask us to reconsider the constellation of social networks that make up a functioning community. And indeed, Tsui presents two animations that not only illustrate in the literal sense, the fictionalized ongoings of the tenement’s interior space and exterior environment, but also demonstrate the City’s significance as a unique settlement free from the clutches of official government laws/rule. Though carved out under precarious circumstances and overseen by even more dubious characters and organizations like crime syndicates, the City as a symbol of resistance remains a kind of persisting glimmer to those oppressed by authoritarian forces.

Kowloon Walled City, an enclave of 16 buildings, was anarchist in nature. Caught in the jurisdictional tug-of-war between the Chinese and British regimes, the city was given a hands-off approach from both sides and therefore left ungoverned throughout the ‘50s to the ‘90s. The city, in fact, thrived and arguably came into full existence from this noninterference. With no laws and no surveillance, it became self-sufficient just like any other, though its seedier side became a dominant preoccupation in the media and to outsiders. Known as “the City of Darkness” in Cantonese, the city only responded to its own internally constructed government and the organized crime syndicates that ran the brothels, drug dens and gaming parlours.2 Far from utopian, it nevertheless housed over 50,000 residents, most of whom lived peacefully together, and was a major producer of food, textile and plastics for export.3 Eventually, despite nearly 50 years of persistence, both Chinese and British governments mutually agreed to tear down the City. By 1994, the city was demolished, and its habitants evicted.

It is with this historical backdrop in mind that we can begin to unpack the show’s relevancy. River of Wisdom (2010), is an interactive 3D animated version of a 5-metre ink on silk scroll, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, by Song dynasty painter Zhang Zeduan (1085- 1145). Zhang’s painting “presents a trading town flourish- ing under a strong imperial government”4—a depiction that negates “decades of state-sponsored oppression and civil unrest.”5 Tsui’s animated scroll Retainers of Anarchy (2017), also the exhibition’s centrepiece, thus actively undermines the idyllic landscape, displaying overt images of dissidence in a similar traditional, flat-style aesthetic. Most of Tsui’s imagery is macabre, such as a hanged scholar or a man being dragged behind a horse, with the rider holding a bow and arrow.

Retainers of Anarchy is a 25-metre long, 5-channel projection animated with surround sound. At the heart of this digital piece lies Tsui’s reimagined Kowloon Walled City, where inside we are shown the diverse activities of the many residents, businessmen and organizations that occupy the tenement. In one particular close-up, the faces of the Three Greats of Wulin are being sucked by a mysterious force while they play Mahjong; in other units, a man is trapped and alone, his lower body crushed and bloodied under a massive boulder; a man lounges on a couch smoking opium; a butcher chops meat with a cleaver in each hand; members of a family work peacefully on separate tasks; the details go on. It’s clear that Tsui doesn’t shy away from the City’s disreputation, and even goes so far as to highlight it, purposefully emphasizing the contrast between his scroll and Zhang’s. Tsui’s version of Hong Kong is spectacular, unkind, grisly and frightening. In his free-for-all world, both inside and outside of the city, there is bloodshed, torture, drug use and a zombie uprising. But beyond this unreserved portrayal, it is in the incorporation of wuxia motifs that these nostalgic references of the City are revived and rejuvenated; their meanings take new shapes and forms that are pertinent today—especially in the face of rising far-right, populist and tyrannical regimes.

Wuxia, like the City, was defiant in spirit. Deemed a marginal genre during the Ming and Qing dynasties, wuxia stories were banned for their promotion of superstitious thinking and for instilling rebellion. Becoming emblems of personal freedom and recalcitrance towards Confucianism and the Chinese family system, these prohibited tales went into hiding, instead finding prominence in outer Chinese territories like Hong Kong and Taiwan. But unlike the City, the mainland Chinese government failed to eradicate wuxia. The 1960s revival of wuxia outside of the mainland brought with it an array of films, which became a central form of entertainment to these local audiences and its continued success into Hollywood, catalyzed by Ang Lee’s critically-acclaimed film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, eventually generating international recognition.

In this way, Lee’s film was a gateway into wuxia for the non-Chinese and international Chinese audience, like myself. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon captures gravity-defying moments: fighters gracefully sail from tree to tree like water spiders. I know that people cannot fly, let alone fight while in flight. But though I rolled my eyes and scoffed throughout Lee’s film, I couldn’t help but lean into the possibility of such fantasy. When I asked my father at the tender age of seven whether or not I could learn to leap higher than the average human being, he told me that Shaolin monks trained their whole lives to be the fierce protectors of their monastery. Later, when Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers was released in 2004, I jumped at the idea that there could actually be a secret matriarchal society that trained female warriors how to curve a thrown dagger. My mind grappled, like the wuxia heroes in these stories, with the difference between “right” (reality) and “wrong” (fiction). In front of Tsui’s considerable piece, I am brought back to the same conflicted state. But it is precisely in weaving wuxia motifs into the imagery of the tenement and its surroundings that Tsui offers the possibility for complete disarray to symbolize still and be, along with the wuxia fighters, a kind of active, present form of resistance against governing bodies and political oppression. Rogue heroes are alive and well, fighting for righteousness.

Visitors can also observe these warriors in closer detail. Lenticular prints mounted on light boxes of stills from the animation accompany the video work along the adjacent walls of the space. Visitors can “play” and “replay” the dark and hostile face-sucking action on the men playing Mahjong. The men’s movements including the speed with which the tiles click, hands move, and faces are consumed, are controlled entirely in accordance with the viewers in real time as they walk past the print. In staging this dynamic relationship between the viewer and the artwork, Tsui allows for the viewers’ role to swiftly evolve into an ambivalent one where passive movements are challenged, intentions come into play, and questions of complacency, power structures and struggles surface. Perhaps here, visitors can be rogue heroes too.

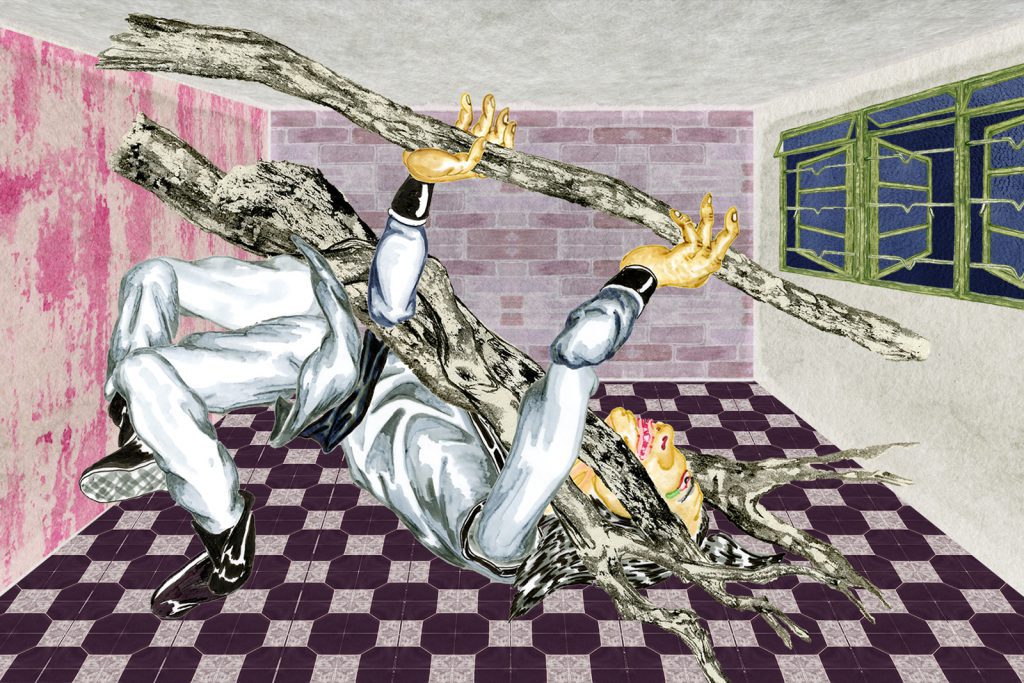

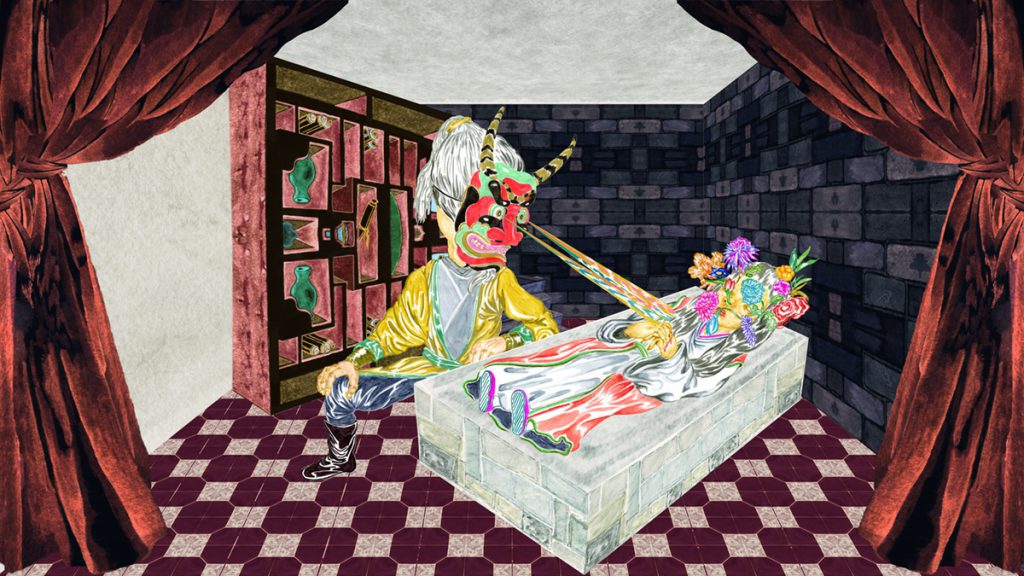

Building upon the opportunity to provide a closer look, Tsui further develops the bustling life within the individual units of the Kowloon Walled City tenement in his single-channel looped animation, Parallax Chambers (2018-ongoing), presented in a separate room of the exhibition space. Featuring the same characters as those in Retainers of Anarchy, Parallax Chambers highlights various scenes that interlace and overlap. In a small square room, a cross-legged wuxia fighter floats mid-air while another balances in a handstand nearby. Next to the upside-down acrobat, an ‘80s cell phone boils with some rice in a clay pot on a portable stove, placed on top of a mini fridge. An abnormally large fish trapped in a claustrophobic fish tank sits against the wall under the window. Cued by the sound of laser beams, the room changes, though not entirely—the fish tank and clay pot atop the fridge remain. Now we see a young maiden tied to a post, threatened by an old man with long hair and a white beard holding a snake. Struggling against her restraints, she spits on him, and the setting transforms again. Sometimes we are presented with a different unit in the tenement building, other times, we are caught in a semi-déjà vu.

Every unit in the tenement shown in both of Tsui’s pieces is cubicle-like, each cramped, all of them tightly packed and stacked, ultimately forming the whole. And certainly, this was also the case in the actual former City, with 40 square feet allocated per person.6 Yet, as Tsui has accurately depicted in his works, the incommodious liv- ing quarters did not confine the people—there was still an enormous amount of activity throughout the City, both within the units and outside. To emphasize this wealth, Tsui even goes as far as to embed AI into the videos whereby they do not loop the same way each time. The nearly infinite number of combinations for the scenes, characters and sound, means that any viewer who comes in at different times would never see the same videos. Placed in context with today’s sociopolitical climate, one could say that Tsui’s ever-changing works of the thriving City allude not only to the current reality of Hong Kong, but to the larger undercurrent of the fight for revolutionary change.

Though Kowloon Walled City no longer stands, would a similar society—or at least a similar kind of freedom—be able to accomplish what governments have failed to deliver? When the CCP forcefully exerts its upper hand, and pro-Beijing politicians invoke emergency power, those fighting for democracy in Hong Kong find themselves and their political values on the heels of peril. I also suspect that in this moment, when democracy is similarly at stake in many countries, I am not alone in quietly weighing the pros and cons of a government-free society or zone (such as Seattle’s Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone).7 Rather than proposing an answer to this speculative what-if scenario, Tsui suggests something stronger: protesters acting as wuxia warriors in today’s violently polarized world. Tsui’s fantastical and fabled world offers up the tangible promise of what could be.

- Giorgio Agamben, “The State of Exception as a Paradigm of Government,” in State of Exception, trans. Kevin Attell (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 3.

- John Carney, “Kowloon Walled City: Life in the City of Darkness,” South China Morning Post, March 16, 2013, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong- kong/article/1191748/kowloon-walled-city-life- city-darkness.

- James Crawford, “The Strange Saga of Kow- loon’s Walled City,” Atlas Obscura, January 6, 2020, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/kowloon- walled-city

- Alexandra A. Seno, “Too Hot A Ticket: ‘River of Wisdom’,” Washington Post, November 12, 2010, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-SJB-2272.

- Justine Kholeal, “Howie Tsui: From swelling shadows, we draw our bows,” The Power Plant, https://www.thepowerplant.org/Exhibitions/2020/ Fall-2020/From-swelling-shadows,-we-draw-our- bows.aspx.

- John Carney, “Kowloon Walled City: Life in the City of Darkness,” South China Morning Post, March 16, 2013, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong- kong/article/1191748/kowloon-walled-city-life- city-darkness.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitol_Hill_ Occupied_Protest

From swelling shadows, we draw our bows by Howie Tsui ran from September 26, 2020 – January 3, 2021 at The Power Plant in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: Parallax Chambers (composite image), 2018-ongoing by Howie Tsui. All photos courtesy of The Power Plant.