Precious Elements: In Conversation with Parastoo Anoushahpour

31 January 2024By Anqi Shen

I can’t say for certain why Parastoo Anoushahpour’s recent film The Time That Separates Us (2022) absorbed my attentions. In the spring, I found myself on the edge of the University of Toronto’s St. George campus in Innis Town Hall, a cinema and lecture theatre. I was compelled to take out my notebook in the dark to record some thoughts: Story of the Ammonites / Lot’s daughters—The key to taking a selfie is to take just one—’Valle’–Yes—There–English—Not everything is meant to be written—All memories become important—A light hand / a Heavy Land.

As part of a 2023 Images Festival screening series called Passages, Anoushahpour’s film was screened alongside the works of Iranian filmmakers Naghmeh Abbasi, Siavash Yazdanmehr, and Rojin Shafiei. Collectively, these works spoke to each other in Arabic and Farsi, between modes and metaphors. I tried to understand the language between them. Shot in Jordan and Palestine, The Time That Separates Us is grounded in the land and the mythologies around Lot’s Wife and the Pillar of Salt. In the film, an intimacy of thoughtful and honest intentions is foregrounded in the exploration of the film’s subjectivities in a heavily mediated landscape.

A couple of weeks after the screening, during a trip to New York City, I reached out to Anoushahpour to ask if she would be open to talking about her work. The Toronto-based filmmaker and artist spoke with me from Athens, Greece, where she was at the time. Our conversation meandered between ideas I had sent her in an email, and we spoke about elements of craft and process—not in a way that would explain certain artistic decisions or meanings, but to more insightfully navigate why I came away feeling so touched by her work.

Anqi Shen: My immediate response to your film was that its strength lay in the attention given to the unreliability of narrative. I found the graininess at the beginning really satisfying, it just felt so aesthetically beautiful. If there was one word I would use to describe the film, it would probably be “unprecious.” Is that how you see it as well?

Parastoo Anoushahpour: No, that isn’t a word that comes to mind, but I really like it. I think in some ways, some elements of it are being treated to feel unprecious as opposed to how they’re usually treated—certain narratives that have power and are very rooted in the culture and the landscape—they’re untouchable somehow, and I guess unprecious and untouchable can switch.

AS: I think what I mean by “unprecious” is that it didn’t seem that everything was pristinely put together. The film came across as personal, and I’m not saying craft wasn’t involved…

PA: Maybe it’s “unprecious” as opposed to that element of control that comes with craft and goes with a certain kind of narrative. There is a level of giving up control in a way that things come together. It takes you out, it breaks the thing it is trying to say. But I like “unprecious.” For me personally, it was a lot about control, and also even practicing a level of looseness that I don’t usually do in my work with my collective—with Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko—we’ve been working together for almost a decade.

Because of the content and form I was working with for this film, it was important to try to find the balance in keeping the responsibility or authority in stringing these versions of narratives along, even though a lot of the texts and the voices that write some of those texts are people I collaborated with over a long time and they’re very much involved in guiding the direction. Those relationships are important to me, so it was about finding a way to keep that precious, and let that guide the image.

AS: What came to you first, was it the story of Lot that you wanted to probe? Or was it the geographic region around the Jordan River?

PA: The thing that drew me to the place was a desire that I have had forever, which was to get closer, or be able to enter this place. Having grown up in Iran until I was eighteen, Arabic is very present, both in the culture and in the education system. You’re taught Arabic from when you’re twelve because of the importance of the Quran. As a kid, I was always very much interested in wanting to know where this language comes from other than this book, that rules my life and everybody around me. Where is the land that this comes from? Because of my passport, strangely, I could never go to, for example, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt; all of these places were only in my imagination … and I had so much imagination about Iraq and Syria through the religious texts, but always at a distance.

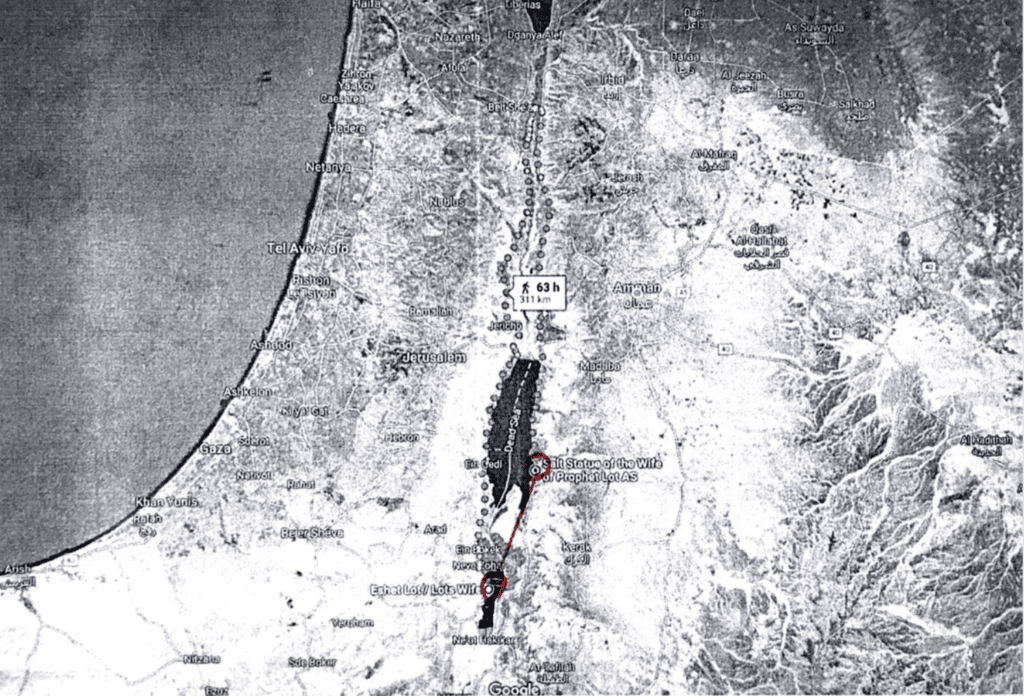

By the time I think I was thirty-one or thirty-two, I got my Canadian passport. That allowed me to return with this other kind of identity and finally be able to enter that place. In 2018 when the film project started, I was extremely lucky to meet a Jordanian/Palestinian friend, Toleen Touq. She was running this a residency program called Spring Sessions that was a group of artists walking from north of Jordan into Egypt for a month and a half. After I heard about it, I really wanted to be part of it, so I did that. I knew that the walk was along the border with Israel, and the occupied West Bank, and north of Syria,. I knew that it was going to be along the Jordan Valley, which is where all the religious sites and biblical sites of the Old Testament are. That all crosses over to the Quran very much.

With Jordan and that specific border, so many of the sites are natural sites, or natural formations, as opposed to built sites. There’s the river where the baptism of Jesus supposedly happened, there’s the cave that Lot stayed in, there’s the Dead Sea that’s supposed to be specific to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, there are the rocks that are Lot’s wife.

Immediately before going there, I knew the rock existed, so I was looking, and then I realized that there’s two of them because of the border. And then that became the thought that there’s two of everything, because of the occupation. You see in the film where my friend Dina goes to Palestine—because again, I can’t go because of my passport—where she films the rock that is much less impressive than the other one, but is the “official” one. This split happens in the baptism site as well, which is towards the end of the film. You see that line in the middle, with the buoyant balls on the water—that’s the border. The River Jordan is layered with narrative, different attempts at ownership through time. So in that way, the instability of narratives becomes important. Everything comes to a very direct confrontation here. There’s the gun, and they warn you that you’re entering a militarized zone. This is the reality of that myth today, the ongoing occupation of Palestinian land. So in that And that was the prompt for the workshops that I was running.

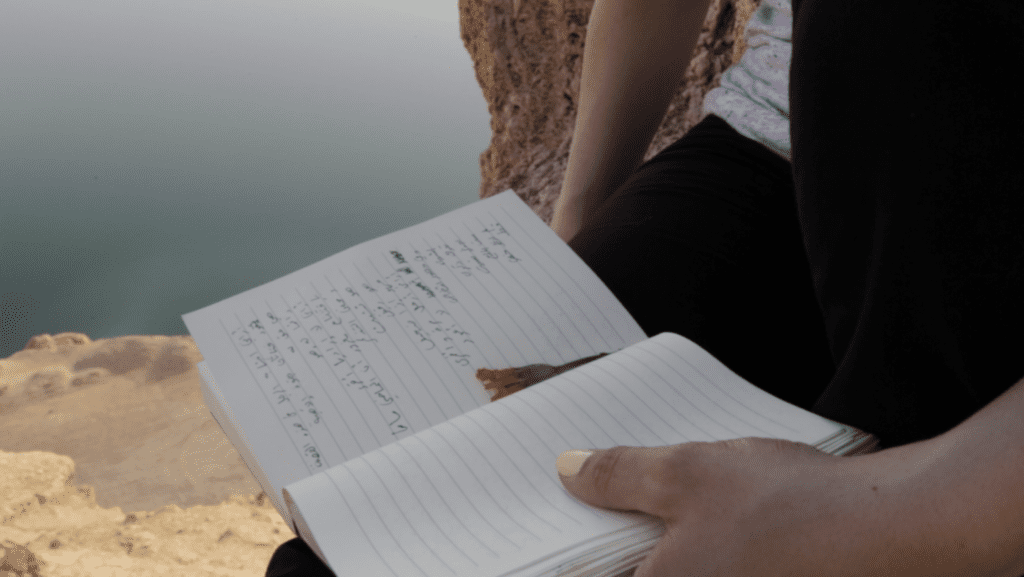

In 2019, I went back to Jordan after the walk for a residency at the MMAG Foundation. I put out an open call to anybody who identifies as queer or a woman to come and imagine what the figure of Lot’s wife would have experienced, or thought, or said. I did site visits, took people there and back, we would watch films, we would look at my editing and what I was moving through with the clips that I had shot. And the idea was like, okay, let’s start thinking about this story together, and then you can continue it into whatever you want the project to be. So it continued for the participants separate from this film. At the time I wasn’t sure if I was going to make a film—at the time it was more an open process of, let’s see what happens.

AS: So it seems like that part—the workshops and the site visits—we aren’t privy to as the viewers?

PA: No, not in the film. A week or two after it premiered, I launched a website working with SAVAC (South Asian Visual Arts Collective). It’s a web project where I have gathered other writings and images by people that took part in the workshops—an expanded process of what ended up or didn’t end up in the film.1

AS: What struck me when I was viewing the film in the theatre was the grainy quality of the film versus the digital images. I’m curious, which mediums did you use? And how did you gesture at and suggest ideas aesthetically that you wanted to explore?

PA: I appreciate that question. One reason for shooting some of the images in both film and digital was to see the kind of temporality they create. There is a duality that is felt in the sites, it is sublime and mundane at the same time. Whether that is a temple or an actual piece of rock, or the seas, there’s a feeling of the Sublime that hits you because it’s so heavy with narrative and story.

At the same time, the reality of it is that it’s this hyper-touristic scene—everybody’s there, making images and taking images—and you’re not there separate from this kind of consumerist economy around you. I also didn’t want to glorify this feeling of timelessness that comes with myths and mythology which suspend you in time, because then it’s apolitical in a way; like you’re being freed from the complexities of the moment.

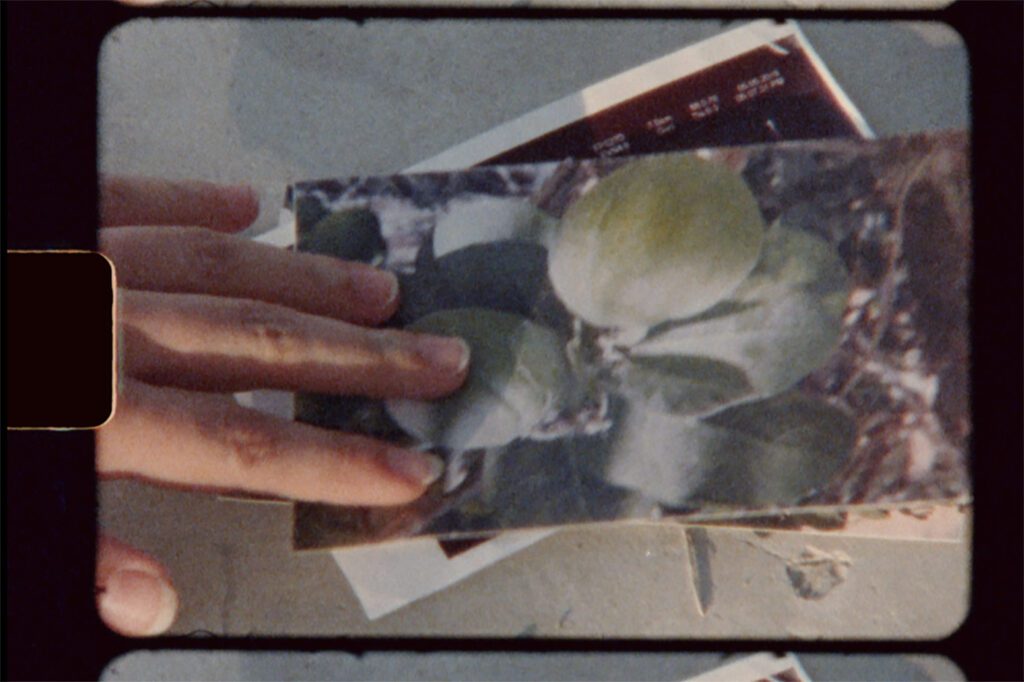

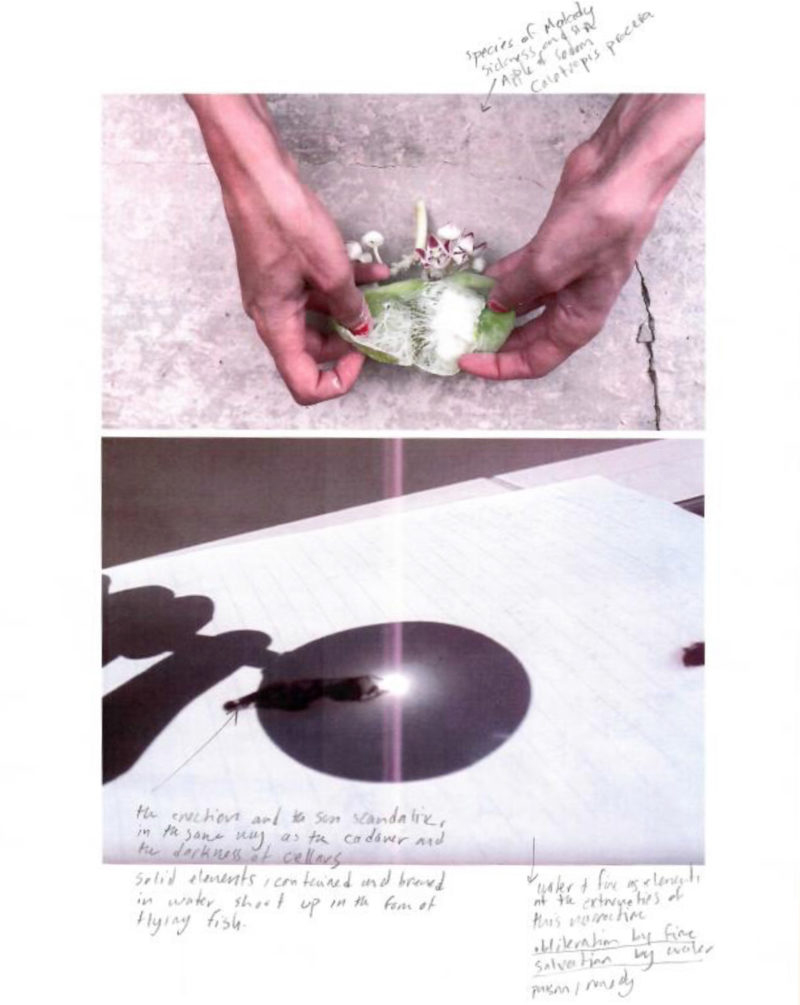

The flickering part, the black and white, is also another way for me to be able to see images that I had shot on my phone completely differently. Through the process of projecting the film on a wall and then re-filming with a really fancy 4K camera, but then bringing the shutter speed down so that the flicker starts appearing, you start seeing the thing differently. And it brings its own rhythm, like now maybe I can bring the voice that I wanted, which is so much about the mythology of that specific plant. The fruit is called the apple of Sodom—it’s poisonous, it holds the ashes of burned cities.

I went around filming fires for a long time (which I never used) in this very beautiful 4K image. One night I was at the place I was staying and there was a fire right across from me, and there was this music playing in the distance. I just had to film it. The grain in the image is from when you get so close—and that’s what the zoom does, you want to get closer—but you end up being further away. It makes the distance between you and the thing somehow more present.

AS: I’ve never heard it put in those ways, about wanting to see something up close, and then having that distance be sort of augmented. There’s a certain level of serendipity about it, as you mentioned, but I think it’s really interesting that to me, as a viewer, I’m seeing the film as if it’s ambivalent to its own reception. It’s not trying to control its own reception; it doesn’t care what the viewer thinks about it.

In your last answer you said, a “beautiful freedom,” and I’ve never thought of film as a medium of freedom. I’ve always found it difficult to have a subject elevate in a film because there have been histories of film being used in ethnography and as a mechanism for documenting people. As a result, I think it carries a lot of that tradition and the medium can be hard to wrangle. It’s a medium that carries responsibility.

PA: I really like this observation. It is true—film has an inherent capturing, controlling quality to it, but the way I was approaching this project wasn’t even to make a film. The kind of works that I’m being drawn to specifically with film are often these militant cinemas and freedom movements that use film, and also certain communities who use film to mobilize a vision of their own. It’s not necessarily that it’s a medium of freedom—it’s not the first one that comes to mind—but it has this potential of projecting some kind of imagination that doesn’t exist for others, and there’s a way to make the films that are absent. You can make the things you want to see.

I always feel there’s an extra step I can take to make the final product more clear, or more digestible to the viewer, and how much of the process I show or don’t show. I don’t know if I care so much about showing everything that happened, because I know what happened and what it meant to me and everyone involved, but to be honest I’m not sure about the right balance at the end—how much holding back is then being intentionally kind of bratty, about holding this thing close for the people who experienced it? There’s fear involved in it, a fear of being misinterpreted.

Language comes in also—do you translate everything to English in this one-to-one way? Or maybe there’s some way to keep only some of that. Then people will have different access to the content, and the people who have shared some of that experience will know a few more things about the details, different accents, little songs here and there—instead of telling everyone what that song was. That’s also a question of access, and who should have total access, and for me it’s more about, for whom am I making this?

AS: I think, in just speaking about this one film, all the things that are held back—all the things you’ve just revealed to me that I did not know before—still come through in the weight of the film. They may not be literally or physically present, but all of those decisions still come through. They may not be intelligible to every viewer but they can be sensed.

I was looking at your other works and you have such an impressive filmography. It seems you’ve really made an effort to continue to create. I feel like this is often the hard part of being on your own terms, that you have to continue to motivate yourself. Do you have any thoughts on how you sustain your artistic practice?

PA: That, I think, is the eternal question. I’ve been really lucky to have Faraz and Ryan. We have really sustained each other, to the point where it was a full-on way of living. We didn’t even know anything would be shown or coming out of our projects. But the centrifuge was so strong we didn’t even care. That also changes. Residencies at the beginning were also about putting yourself in relation to others who are struggling, and figuring out how to sustain your life, and keep your brain sane, and your body okay, and finding money to fund the project.

I think more and more it’s about how to sustain that creative energy or that desire to create. That becomes looking for inspiration in other artists, and lives lived, and how people you respect did it. I’ve been lucky to be in Canada in so many ways, of having enough funding to have that balance of small-scale, very experimental ways of doing and living—that is something that Canada has allowed me to experience. But then there’s the isolation that comes with it, and you have to reach out to other places and see how they do it. It’s a constant searching, and looking, and being in conversation. I also know it’s not an ideal formula for everyone. It’s worked for me because of my background in theatre—I’ve believed in that messy, multi-directional way of thinking and the support that comes with it. One of the most meaningful parts of making work for me is that when something good happens, that joy is shared.

- See the project here: https://missedconnections.art/artists/parastoo-anoushahpour/

The Time That Separates Us (2022) by Parastoo Anoushahpour screened as part of the Passages series, curated by Jaclyn Quaresma, at Images Festival in Toronto, ON on April 26, 2023.

Feature Image: Film still from The Time That Separates Us, 2022 by Parastoo Anoushahpour with Bayan Kiwan. Photo courtesy of the artist.