Shape of Dance

12 August 2020

By Juilee Raje

My friends shudder when I bring up the story of when I bit into a glass as a young child. As the story goes, I could barely see past the table at a restaurant, surrounded by indolent chatter from my family. In the middle of the meal, as my father recalls, he heard a terribly conspicuous “tok” sound—my family looked over in horror to see my teething mouth closed over a wine glass, little hands clasped happily around the stem. I may have simply been practicing being a sculptor with an unconventional method, because when they pried my mouth open, out came a perfectly intact piece of glass.

Fortunately for crystallophiles like me, Jerre Davidson’s Shape of Dance, which exhibited at the Elora Centre for the Arts, offers a stimulating take on glass art: one that’s in dialogue with contemporary sculpture’s relationship with movement-mapping technology. My partner and I made the trip to Elora on a Tuesday evening, cutting it close to closing time. We entered into the darkness of Minarovich Gallery, stumbling for the first few moments. Dimly illuminated bodily forms propped onto plinths and walls waited patiently as if they were dancers on a stage, painstakingly holding their pose behind a drawn curtain—until the curtain was drawn, and they sprung into dance in the light.

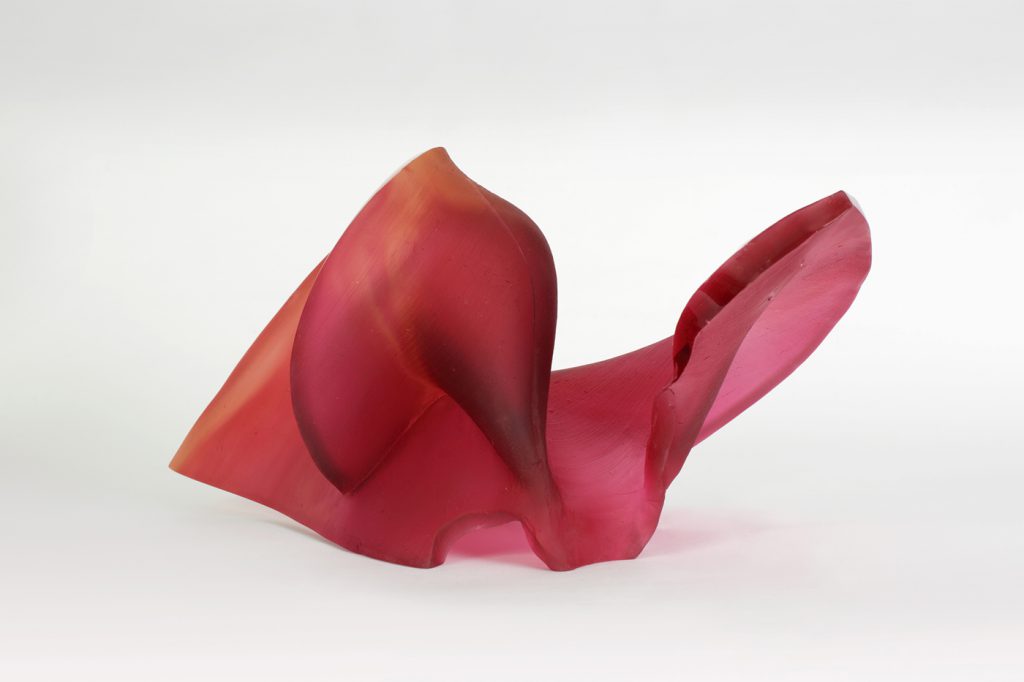

The first thing that struck me was the weight of the flexuous glass works. Though their bodies fluidly contorted themselves into unplaceable postures, they held their integrity as if standing firmly on their legs. Like fingerprints or DNA, each piece was slightly distinctive from its neighbour, as if belonging to the same family but born from different moulds. Though some were strategically grouped by colour to represent the traditional costumes of particular dances, others were more relaxed and exclusive in their postures and colours. My expectations were slightly upended; far from lithe and delicate as is associated with glass (I would know, since I’ve literally sunk my teeth into the material), the abstractly sinewy figures stood strong and resilient, like athletes with a strenuous commitment to corporeal transcension. With a few exceptions, the sturdiness of the forms emanated a sense of self-containment, moving within a fully achieved stage of development.

Wall installations resembled group dances assembled in horizontal succession or choreographed groupings, while individual glass works were propped onto plinths. Around the corner, three glass figures performed a Pas de Trois (2019) atop a slick black grand piano. The ballerina music box-like display of the piece was executed with such care that it became the showstopper, inviting the viewer to take a seat at the piano just to observe intricate crevices running through the small sculptures. The wall installations, especially Flamenco (2019), achieved a sense of interconnected tension: within an arrangement of expressive group storytelling, the smooth texture and engrained movement recalled a gust of wind blown from the heavy fabric of a swooping burgundy skirt. There was a certain undefinable fillip and poetic energy behind the group’s “performances”. In comparison, the rhythmic relation between works on plinths brought together was missing; figures danced around their autonomous selves rather than in synchronicity with their surroundings.

One of the medium’s most admired features is its translucent surface, which has an ability to create a vast interplay in colour tonal qualities as light filters through. Likewise, Davidson’s work offers the viewer such a generous palette; pulling baby pinks from tulle skirts and the deep rubies of flamenco gowns, along with the more experimental tones of Prelude (2019) and curaçao blues of Nocturne (2019).

There is remarkable seamlessness and nonuniform depth to the works which is a result of the unique process employed: Davidson has endeavoured to slip out the stitches separating the realms of art, math, graphics, and programming, and mold them into a different, more blended operation. As a looping video informs the viewer, the process behind the project involved Elora-based dancer Meredith Blackmore performing various dances in front of an OptiTrack multi-camera system at Fast Motion Studio in Toronto, while wearing motion-sensor clad clothing. Experts at FMS developed code which then converted the movement pathway recordings into a format compatible with a 3D printer. Proceeding steps involved rubber moulds covered with a heat withstanding plastic silica mixture, into which chunks of glass were then poured and fired in a kiln at a high temperature. Once everything has cooled, out comes the sculpture.

These aforementioned steps are posted on the walls alongside artworks, written in an accompanying publication, as well as reiterated in the film outlining Davidson’s process. The heavy-handed repetition of information overshadows the display of the works at times, as the reading of the space then leans more toward a laboratory with the light turned towards the artist, rather than to the fully executed works. With the weight of the information leaning on this singular process, we’re inclined to perhaps view the work too closely, too literally. Audiences are encouraged to let themselves feel the ecstasy of dance and the shapes that are created through a performer’s limbs and pathways of movement, mimicked in the Sinuous (2019) artworks, but rather than being able to fully immerse in this inaudible expression, there are answers offered behind every mystery, ready to catch every fall.

The question I can freely fall into is, what comes next? Is Shape of Dance a nucleus for something bigger, or perhaps something even more detailed? What are our emotional reactions to mapping the movements of and through our bodies, chiseled into solid artifacts for the translation of one art form to another? And what modes of expression should we select to immortalize, knowing that this is a possibility? The instincts behind giving life to these ideas in the first place are ambiguous, yet somehow inexplicably human.

Jerre Davidson’s serene and resonant glass dancers—twisting, pirouetting, spinning, elongating, resting—have beautifully demonstrated how to probe and collaborate with seemingly unlinked disciplines and preserve the results as trophies. The exhibition maintains a neatly controlled and self-contained presentation of Davidson’s art making process from conception to final product, yet instead of being a tightly-coiled process, these ideas could leave the purpose and artistic-scientific contributions of such explorations between S.T.E.A.M. experts and contemporary glass artists more experimental and open-ended. It remains to be seen how the torch will be passed onto the next local artist, and how this initial spark spreads to a fire.

Shape of Dance ran from January 9 – March 8, 2020 at the Elora Centre for the Arts in Elora, ON.

Feature Image: Rose Spiral, 2019 by Jerre Davidson. Photo by Sylvia Galbraith.