Silver 35: Mike Goldby at Sibling

27 March 2019

By Parker Kay

How am I going to get to The Junction to see this show?

As I think about the various routes I might take to arrive at Sibling, I realize I am staring blankly at my phone, whose screen has since locked. I find myself in what I have learned to identify as social paralysis, the experience of the body locked in stasis when confronted with social planning—it happens a lot.

I scan between my transit options: bus-subway-walk, walk-bus-bus, bus-streetcar-walk, or what looks like my quickest option: bus-subway-bus-walk. I decide to abandon it all and walk the whole way. Google Maps tells me it will take 53 minutes.

When I arrive, I note the distance between the front door and the exhibition space; I appreciate the extra time I have to make the perceptual shift between city street and art gallery. This shift can often feel like a jump cut in a movie, where the contrast between shots is like a collision that jolts the viewer into remembering that this is, in fact, a movie, and not reality itself. In contrast, the distance from the front door to the exhibition space seems more like a gentle dissolve. As I enter Mike Goldby’s solo exhibition Silver 35, I realize this oscillation between the city and the gallery is also implicit in the work itself.

For Sibling’s inaugural exhibition, Goldby has mounted a series of nine large photographs that depict street scenes of Toronto’s downtown financial district. At a cursory glance the photographs could be categorized as “street photography,” one of the medium’s most tried genres, and one that often conjures images of canonized figures like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, and Robert Frank. However, Goldby wisely sidesteps this reading of the work through utilizing an impressionist experience of the city. By avoiding any sort of depiction of a traditional subject, Goldby captures traces of an experience of the city as opposed to a depiction of the city itself.

The obscured compositions of the artist’s images make them appear more like memories, with each element in the frame rushing towards the viewer simultaneously. The picture plane is rendered flat as hierarchies between foreground and background dissolve. Men in suits are cropped at the head, slices of skyscrapers appear through crowds of out-of-focus pedestrians, and clothing transforms into abstract blocks of colour. Together these elements contribute to an overall impression of an event, one that hints at a totality of experience felt through the body.

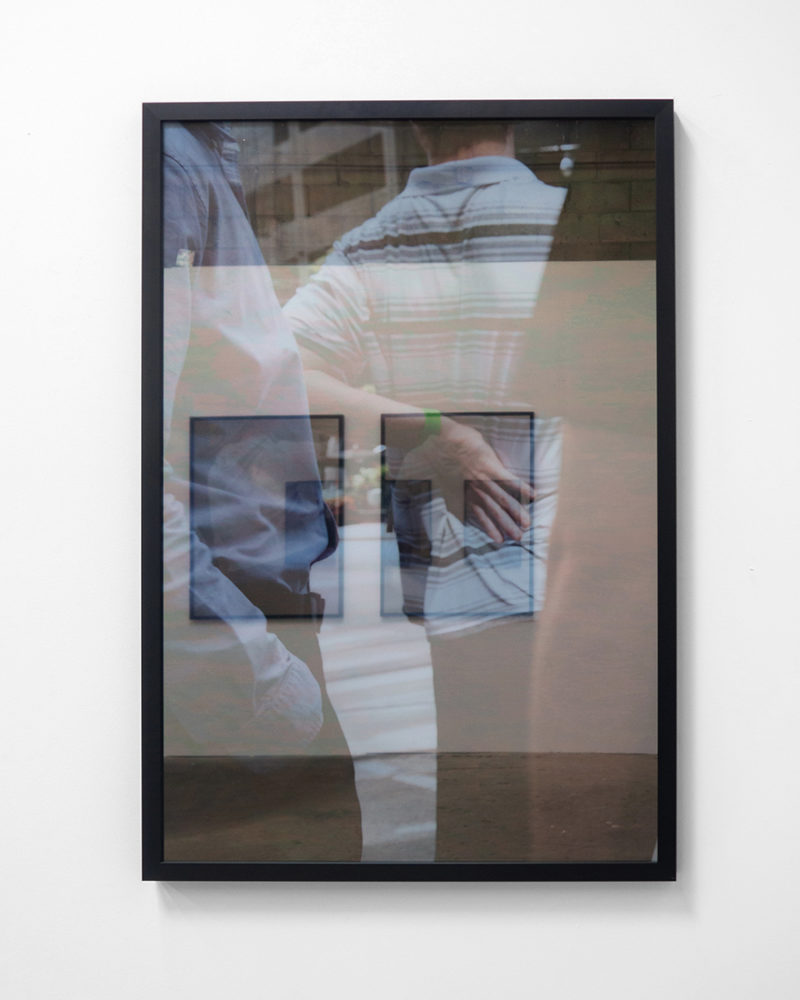

Additionally, the display mechanism itself plays a significant role in recreating multiple transitional cityscapes within the gallery. By addressing the structure of the work, the photographs act as a window that depict an image of the city while also being a mirror that reflects the lived experience of the city that the gallery resides in. The artist achieves this by combining digital inkjet prints with a solar tinting film mounted directly onto the protective glass of the frame. Typically used on street level office or car windows for additional privacy, the film provides a curious reflective threshold between the viewer and the image. Looking through the film towards the photograph, I also encounter my own reflection, an inverted view of the gallery space, and glimpses of the rest of the exhibition. The images now appear as if animated, the contours of bodies shimmering as this double exposure draws my eyes into a dance back and forth between the depicted images and the reflective threshold. Like a zoetrope, this flicker between the image of the city and the experience of the city quickly transforms from a glimmer to a smooth synthesized image. This reveals an experience of the work that exists in the liminal space between the image and the actual, a space that dissolves between fixed and the pliable.

In film, a dissolve is a popular editing technique used to transition from one shot to another. However, exactly halfway through the dissolve, both shots appear on screen together, a fleeting double exposure that creates a bridge between two worlds; a fleeting moment too quick for the eye to fully take in. Goldby’s prints, seen through the solar tinting film, achieve a similar synthesis. The architecture of the gallery and those within it—become inextricably linked to the experience of the city depicted in the photographs. Traditionally the white cube stands in stark contrast to the chaotic life of the city, encouraging quiet contemplation over car horns and people on their cell phones, and is even compared to the temple or the mausoleum for its capacity to reduce and eliminate distraction in the service of focused worship. Goldby’s subject matter rejects this in favour of a visual experience akin to the white noise of the bustling city. Amidst the chaos, it almost feels like you are in your own personal bubble where no one would notice if you took someone’s picture, yelled and screamed, or dropped something on the ground.

A flatbed print on bent aluminum sits unassumingly on the gallery floor, disguised as a 8.5” x 11” sheet of paper accidentally dropped by one of the photographs’ abstract subjects. Playing with the tension between art object and a mislaid document, the aluminum print contains a text that describes Goldby’s ritual of visiting the downtown locations depicted in his photographs. The first line of text reads, “I usually come downtown to the Financial District to clear my head.” This introduction is brief but telling; here Goldby reinforces the interplay between the built city and the space of the mind.

From this point forward the text reads like a psychogeographic map that Goldby navigates on foot. Musings about particular buildings are generated from a practice of daydreaming and emotional disorientation rather than the linear progression that our city’s grid plan is built upon. There is a moment in Bennett Miller’s first feature film, The Cruise (1998), where the documentary’s protagonist, Timothy “Speed” Levitch, discusses the unoriginality of the New York City grid plan. “Speed” Levitch, a modern-day flâneur and NYC tour guide, goes on to discuss that being forced to walk at right angles breeds homogeneity and leads us to make the same mistakes our parents did. The antidote to this urban tragedy is what “Speed” Levitch calls cruising, a take on Guy Debord’s dérive, that encourages unplanned and meandering routes through the varied ambiance of the city in order to activate thoughts and feelings otherwise inaccessible. Goldby’s photographs and text act as a trace of his personal experience of Toronto’s unique psychogeography. More importantly, however, they create a rupture in the gallery which places the viewer at the centre of this liminal space and encourages them to look around in search of their own memories and experiences.

The work in this exhibition is in some ways very consistent with Golby’s previous work. The photographs employ a similar compressed layering of picture planes found in previous exhibitions such as Core Exposed (2015) at MonCHÉRI in Brussels, or more obviously in his series titled, Pedestrian Studies (2018) shown in the ongoing outdoor exhibition Puddling. However, new to Goldby’s practice is an unmistakable element of autobiography which adds a welcomed warmth to the austere aesthetic his work tends to employ. The evidence of Goldby’s embodied experience is the catalyst for the aforementioned liminal cityscapes to appear. I think back to my 53-minute commute. I started in Parkdale, then went west to Roncesvalles, north through the industrial Rail Path, and finally emerged in The Junction. However, this sort of variety in urban ambiance is atypical in Toronto—you have to search for it. Silver 35’s success comes from the bread crumb trail that the viewer follows towards the realization that there are worlds yet to be discovered somewhere between the cinema of the mind and the rigid materiality of the city.

Silver 35 ran from November 17, 2018 – January 5, 2019 at Sibling in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: First Angle, 2018 by Mike Goldby. Photo by Holden Kelly courtesy of Sibling.