Steven Beckly: Handy Work

2 October 2025By Adrien Sun Hall

In Handy Work, Steven Beckly’s third solo exhibition with Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto, the artist turns dramatically staged elements of light and form inward. Known for his sensually evocative, sculptural approach to photo-based installations, the artist returns to the self-contained image in a series of wall-mounted and framed photographs of hands holding, twisting, grasping, and gripping each other in a series of intimate gestures. In the photographs, the hands appear as dramatic figures, lit by direct sunlight in a dramatic chiaroscuro effect against their shadowy backdrops. Amidst a layered background of camouflage-printed fatigues, military-grade wool, and army-green netting, Beckly’s hands deftly weave a rich semiotic history of his Vietnamese Chinese family’s past.

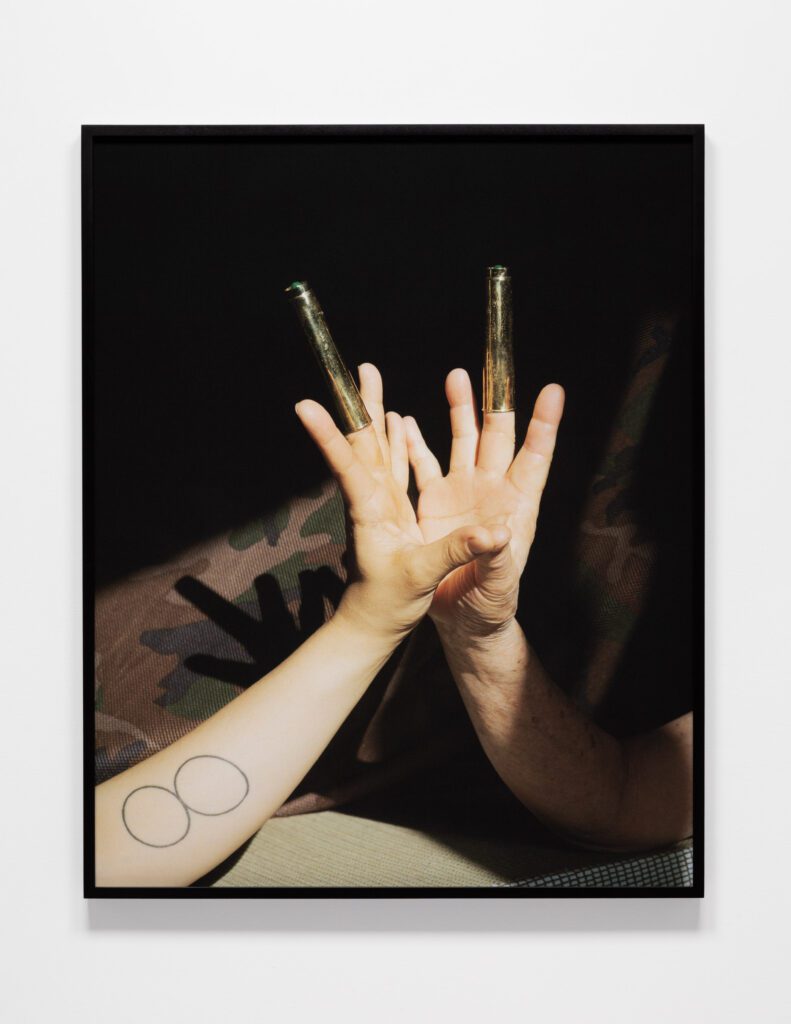

Handy Work explores the artist’s relationship with his aging father, a Vietnam War veteran. Born in Vietnam to Chinese parents who fled Southern China to evade the Japanese occupation, Beckly’s father found himself amid another conflict as a young man. Recruited as a weapons technician for the Southern Vietnamese Army, he was posted to various sites where he would fix and prepare weapons and machinery, his skilled hands protecting him during a brutal war.1 The photographs feature Beckly’s and his father’s hands, often mirroring each other, contrasted by the appearance of youth and the subtle lines of age. In Hidden Power (2025), their hands emerge from the darkness to meet poised in sunlight, thumbs and pinky fingers touching while the others reach outward, their palms open towards the sky. Together, they form the padma (lotus) mudra, a hand symbol representing spiritual awakening and the opening of the heart’s centre.

Throughout the exhibition, the photographs feature various mudras––ritual gestures practiced in Buddhism and other spiritual disciplines that direct the flow of energy within the body and convey various teachings. To those familiar with Buddhist temples, the photographs in Handy Work are deeply evocative of the thousand-armed manifestation of the Chinese bodhisattva Guan Yin (觀音), her many arms a representation of her immense power to simultaneously perform countless acts of compassion. Each of Guan Yin’s hands forms a mudra or wields an instrument symbolizing skillful means of the Dharma. In Beckly’s titular piece, Handy Work (2022), his father’s weathered hands form the dharmachakra (turning of the wheel) mudra, his palm facing the viewer as though a bodhisattva himself, offering a blessing.

His raised hand wears two brass rings shaped like bullet casings, wrapped with textures of the Vietnam landscape—the surface of water and the rib of a tropical leaf. Each photograph in Handy Work features various cast brass adornments 3D-printed by Beckly with jewelry designer Valerie Lamiel, modeled after various forms of ammunition. In A Different Speed (2025), a fragmented spider web of fine gold chain spans the frame, veiling a backdrop reminiscent of a dark forest floor. A hand with open palm reaches in from the left, punctuating the web at its centre with a single fingertip, capped with a gold bullet. In 62156227 (2025), a three-segmented ring inlaid with a jade fingernail is stamped with Beckly’s father’s military number. The rings glimmer like the gold statues of bodhisattvas. In many of the photographs, the brass rings elongate the fingers, recalling the ornate fingernail guards of aristocratic women in Qing dynasty China, whose long nails were markers of beauty, power, and their distance from manual labour. Deftly mixing these visual histories, Beckly explores dichotomies between masculine and feminine, aristocrat and labourer, frippery and practicality, extravagance and restraint.

There is a distinct sense of theatricality and queer affect to the careful staging of Beckly’s photographs. Three smaller works presented together, Covert Tactics (2025), Twist of Fate (2025), and Shading the Truth (2025), read like a play in three acts: a semiotic drama of hands unfolding in spotlight and shadow. The absence of facial expressions emphasizes the gestural, a tactic used in many traditional East Asian forms of theatre. I am reminded of the hand gestures employed in Cantonese Opera, and of its long, rich history of actors playing cross-gender roles. In the practice of nàahm dáan (男旦), male actors playing female roles relied on delicate and poised hand gestures—many drawn from mudras—to carry great depths of meaning. Guan Yin, too, was historically understood as having no gender, taking the form of any human or non-human being, male or female, though she later became an embodiment of feminine ideals in Chinese folk religions. Beckly’s use of these hand gestures inflects the images with a queerness that challenges the commonly restrictive gender norms of a father-son dynamic. Similarly, the photographs juxtapose Chinese traditions of gender-ambiguity, role-play, and performative fluidity with militarized masculinity, challenging the binary cultural authority imposed by successive modern Chinese governments.

During Beckly’s childhood in Canada, his parents spoke little of their wartime lives and, due to their migratory history, he grew up with few photographs of his family’s past. Beckly has spoken of art requiring one to “make room for lightness and darkness within one’s self,”2 and in many ways, these new photographs revisit a dark or blank period, creating images of a family history left behind. But they also use spiritual practice and gesture as a form of healing, remaking this history in their own telling, revisiting the traumatic theatre of war with the theatre of photography. In Handy Work, Beckly has created a new embodied semiotic, referencing a familial history of migration, trauma, warfare, gender, resilience, and faith. The meanings of the hand gestures are brought into being as they are practiced, invoking a kind of gestural talisman, an act of protection, and a declaration of knowledge and strength.

During the making of this body of work, which began in 2022, Beckly’s father was diagnosed with colon cancer. The caregiving required by his illness introduced a new level of intimacy within the family, which Beckly cites as an inspiration for the work.3 Beckly’s photographs complicate common cultural views of aging and critical illness as tragic, sombre occurrences, filled only with mourning for youth and healthier times. Instead, the artist repositions these moments as opportunities for intimacy, the sharing of untold stories, and the formation of new languages of love. The photographs in Handy Work highlight Beckly’s deft use of light and shadow, opacity and transparency, veils and nets, layered one on top of the other to magnify the ineffability of their complex subjects. Yet somehow amongst the many shadows in this multifaceted layering, something simpler and clearer begins to be revealed: a transcendent portrait of father and son.

- From Steven Beckly: Handy Work, 2025 video from Daniel Faria Gallery accessed at danielfariagallery.com/exhibitions/handy-work

- From a conversation with the artist, April 26, 2025.

- Ibid.

Handy Work by Steven Beckly ran from May 1–June 14, 2025 at Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: Steven Beckly, Twist of Fate, 2025, archival pigment print, 25″ x 20″. Photo by LF Documentation courtesy of Daniel Faria Gallery.