The Oral Logic by Xuan Ye

8 July 2020

By Emily Fitzpatrick

In the early 2000’s, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), an agency under the United States Department of Defense working on social forms of Artificial Intelligence (AI), began to develop machine-learning agents that could cognitively engage with each other, their environment, and essentially ‘learn’ from their experiences in a simulation. During one simulation, two learning agents named Adam and Eve were programmed to know some things (how to eat), but not much else (what to eat). They were given an apple tree and were happy to eat the apples, but also made attempts to eat the entire tree. Another learning agent, Stan, was introduced and wanted to be affable, but eventually became the loner of the group. Given the natural development of the simulation—and a few bugs in the system—Adam and Eve began to associate Stan with food and one day took a bite out of him. Stan disappeared and thus became one of the first victims of virtual cannibalism. (1)

This curious, yet ominous anecdote provides the basis for Xuan Ye’s solo exhibition The Oral Logic at Pari Nadimi Gallery. Supposing learning agent Stan’s fate was a mistake in the simulation, does the fault of the glitch lie in the negligence of the human programmers? AI intuition? Or, perhaps, a bit of both? Ye’s exhibition draws on the narrative poetics of these machine-learning binaries, both predefined and probabilistically intuitive, while considering systematic errors as opportunities to both question and reconfigure our understanding of AI and its aesthetics.

The aforementioned story of Adam and Eve, which provides the foundation for the exhibition, is told through the interactive, multi-media work ERROAR!#4 (2019). A large, metal structure resembling a tree displayed several screen-based machines and reflective surfaces. A text which alluded to the story is printed on scrolled paper, tangled across the structure’s branches. Viewers were encouraged to interact with the screens, which mirrored their faces, and when approached revealed skewed, unnatural reflections of themselves looking past the screens, rather than an expected 180 degree perspective. This meta-reflection faced away from the interaction with the sculpture, as if to resist further engagement with the machine or possibly resemble an error in the experience—calling to the errors that killed Stan.

The exhibition’s central theme is our contentious marriage to technology, or, how our mental activities continually merge with the operational systems of our personal tech devices. There is certainly a corporeal quality in the way we navigate our electronic landscape: we consume infinite amounts of imagery and information, feed off of virtual affirmation (views, likes, follows), and absorb the weight of user-based interaction and fatigue. Ye’s use of the analogy of virtual cannibalism helps the viewer to reflect on both the complacency of our engagement with technology as well as the hidden politics and dangers of modern technology’s machine-learning abilities. At a time when we willingly volunteer our data to be shared on various apps and platforms, only to have it extracted and sold back to us through targeted advertising, The Oral Logic asks to what extent can humans and technology evolve together to envision a more mutually beneficial form of existence?

An imitation, 3-D printed saber-toothed feline skull sits below the screens, alone and quiet on a small platform, like a memorial for a spectuative, archaeological dig. While its relevance is unclear, I can only guess that its presence reflects another era in which humans potentially co-existed with a species beyond their comprehension and intelligence. Even further, the placement of the skull at the base of the tree could also reference religious imagery of Adam’s skull at the base of Jesus’s cross, which again calls to a perpetual theme of the exhibition in which we are reminded of the predetermined and intuitive binaries of narrative–particularly when considering these AI samplings.

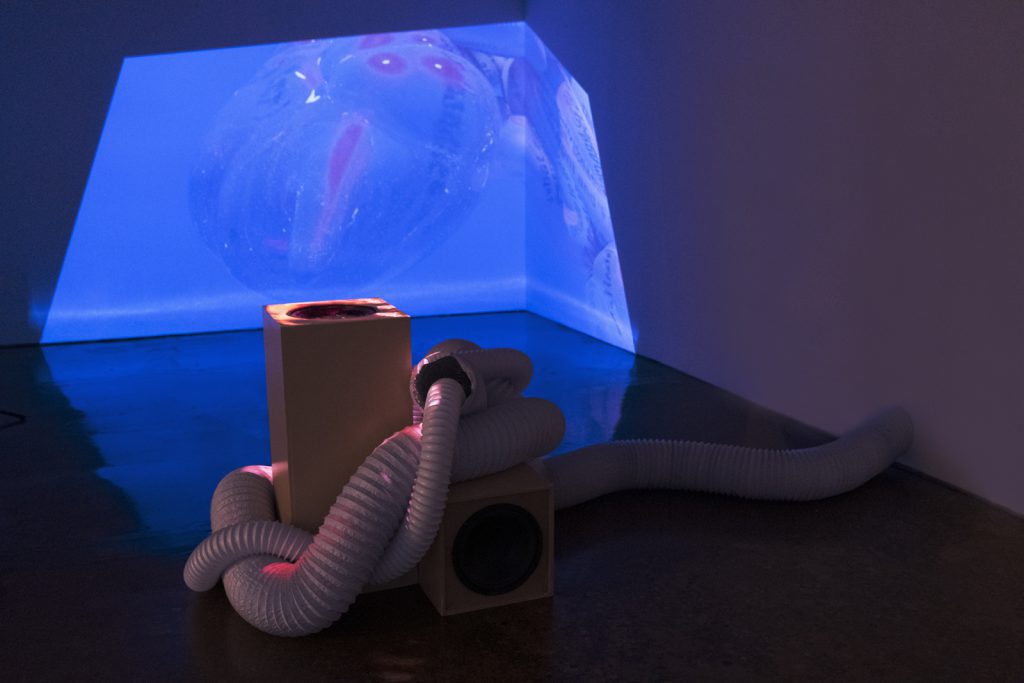

In the centre of the space, the two-channel sound and animation installation, Garrulous Guts (2019), wraps around an entanglement of air ducts. The work’s audio was created through a collection of sound footage from online searches for “people vomiting” and speech clips generated by WaveNet, a feedforward neural network (2) for generating advanced Text-to-Speech results. While the speech was trained in English, that was not what was heard emanating from the installation. Ye created new speech that were, quasi-English, which were then interpreted into sounds that didn’t make sense to English-speaking viewers or would even register as a recognized human-based language, potentially creating a new human-machine hybrid language. Despite its mechanical and cryptic tone, the soundtrack held some familiarity in structure and pace for my auditory sense to digest as dialect. However, I’m not sure whether this perception was made possible because of Ye’s pre-defined, human application into the AI, or the visceral essence of machine-learning.

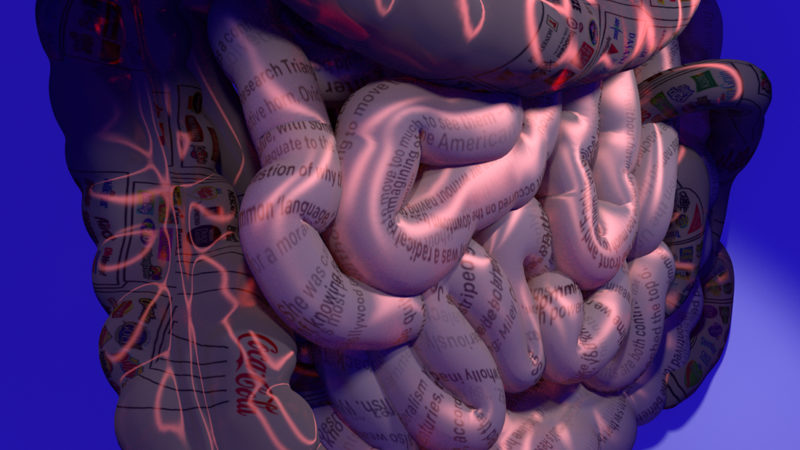

The animation portion of Guts consisted of two projections. One washed over the air ducts and subwoofers, providing the installation with a pink, almost bodily glow. The second projection was against an adjacent wall, stuffed to the side in the corner. It displayed a floating digestive system, with pulsating intestines tattooed with moving text. Topics such as the Civil War, unicorns, and Miley Cyrus were covered as the text moved throughout the projection, like in news headlines. As the title suggests, the world’s most trivial information seems to be the only content we can afford to digest in our current state of over-saturation.

Mounted on the wall was a triptych of circular inkjet prints, resembling microscopic photographs, titled, Deep Aware Triad (2019). Ye explored how the body and technology process images by attributing a chosen theme and associated keywords to each circle: Spinal, Oral, Hormonal. During production in Photoshop, Ye used the Content Aware Fill tool to stitch the photos together (a quasi-AI function of the Adobe Suite designed to remove unwanted objects from a photograph and replace them with new image details from the surrounding area). While the function is quite accurate, Ye purposefully misused it to create preliminary errors to obscure the borders between the collected images, eating away at their assumed forms.

Similar to Garrulous Guts, Ye inserted errors into the human-made components of the Deep Aware Triad triptychs to survey how machine learning reacts. In relinquishing some agency and control for a finished product, a new language for cognitive processing was revealed. The AI was left to its own devices and was forced to follow its “gut instinct” to invent. Indeed, the application of digestive-based imagery throughout the exhibition was warranted, as the gut biologically and symbolically drives human instinct and clairvoyance. The Oral Logic left the viewer to wonder whether the workings of some artificial intelligence are in fact advanced enough to be comparable to that of human “gut” reactions. Was Stan’s disappearance an error in the system, or a coupling of machine and human understandings for requiring the basic needs for sustainability and survival?

1. https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-creepiest-thing-any-AI-has-done-so-far

2. https://deepmind.com/blog/article/wavenet-generative-model-raw-audio

The Oral Logic ran from November 14, 2019 – January 25, 2020 at Pari Nadimi Gallery in Toronto.

Feature Image: Installation view of Garrulous Guts, 2019 by Xuan Ye. Photo courtesy of the artist and Pari Nadimi Gallery.