The shape of your face, the speed of your speech

14 May 2021

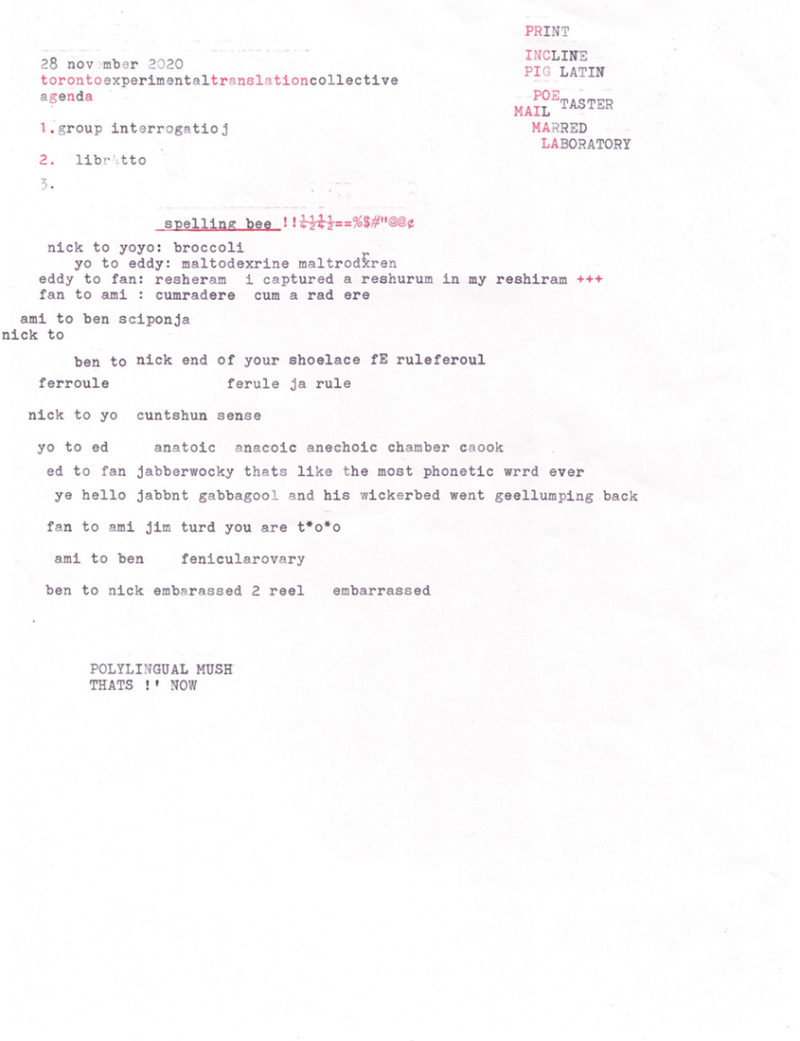

The Toronto Experimental Translation Collective (TETC) is a group of six artists and thinkers: Benjamin de Boer, Nicholas Hauck, Fan Wu, Eddy Wang, Yoyo Comay, and Ami Xherro. The collective first met and lived together at Artscape Gibraltar Point on Toronto Island in summer of 2020. Since then, they’ve been exploring the possibilities of collective translation. Their latest residency was in Qualicum Beach on Vancouver Island. They are recording an album to be released this year.

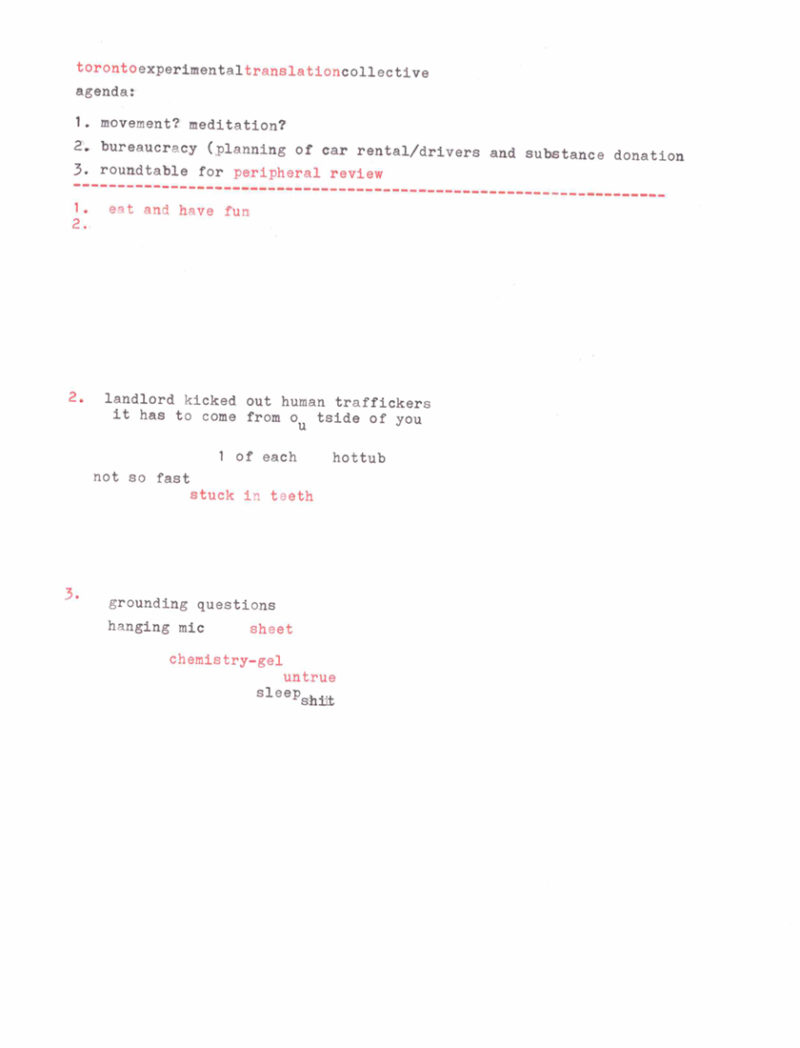

In this live garden interview conducted in Fall of 2020 around a suspended microphone, Xherro and the rest of the collective discuss alterity, meaninglessness, intuition, transcription, and zoology.

On Identity…

Ami Xherro: Let’s begin: who is the Toronto Experimental Translation Collective?

Nicholas Hauck: I think TETC comes together at the crossroads of translation and creative practice. As a creative practice, translation’s process is as important, if not more important, than the product itself. And it’s an intrinsically collective exercise.

Fan Wu: I was responsible for recruiting the members of our society—collective—on the basis of their potential gelling with each other, chemistry-wise, and what happened was that they gelled…

Yoyo Comay: How did you figure the gel?

AX: Was it at all based on translational capacity or mostly just interpersonal success?

NH: A sliding scale?

FW: Yes, it’s a spectrum, a doubly inclusive spectrum.

Eddy Wang: Everything’s translation.

FW: Say more about that. That is a principle we’re starting with.

EW: TETC is a group of artists and thinkers who want to sit with and seriously contemplate this idea of what is translation and not just, you know, the clinical definition of translation. We’re applying translation as a bridge between theory and bringing our differing backgrounds together as a collective in order to seriously address these issues of translation.

YC: And unseriously address them as well.

NH: Play is part of it. It has to be.

EW: We take seriously play and we take seriously unseriousness.

Benjamin de Boer: I guess the group chemistry allows for our individual interests to not just be parallel discussions, but combined, mixed up. We blend our own desires into collective desires, as opposed to aligning under different slogans.

NH: Ya! To think as a collective, to get rid of the self that is so embedded in our languages. I think translation is a very good practice for getting rid of the self.

FW: So there’s something about translation and collectivity—both of these practiced concepts are also aligned with each other.

NH: Too often the translator is seen as a lone linguistic cowboy, and I don’t think that’s true. The translator is always in the liminal space of the Other—other text, other writer, other language, other process. Dualism—translator/writer, copy/original, individual/group—doesn’t account for the collective networks that make up all translation. I don’t think one can be a translator if the self is the foundation.

EW: I would say our point of departure from most normative practices of translation is this idea of collectivity. I like the metaphor of chemistry, like we’re chemical elements that are creating bonds, trying to produce a substance not yet seen in this periodic table of translation.

AX: I think a lot of our translational projects have to do with dissolving the surface of a text. How is it easier to be together when we’re trying to destroy the facade of language? Does it help us get closer, does it enhance our collectivity, to have this destructive attitude towards normative language?

BB: Are we destroying a language in order to speak baby language? Or just live in a vacuole of non-communication?

AX: Is that what we’re doing? Making a baby language?

NH: I think as a collective we have that assurance of others, so the anxieties of not having a language, when you’re by yourself—What am I gonna do? How am I going to say?—are eased. To collectively occupy the space of no language, where communication is unfamiliar, as language is in the process of being destroyed or dismantled or decontextualized, or…

AX: Do you think it matters how many languages we entered with?

NH: I don’t think it matters.

AX: But does it work in this way—that the more languages you speak the more eager you are to find ways out of them?

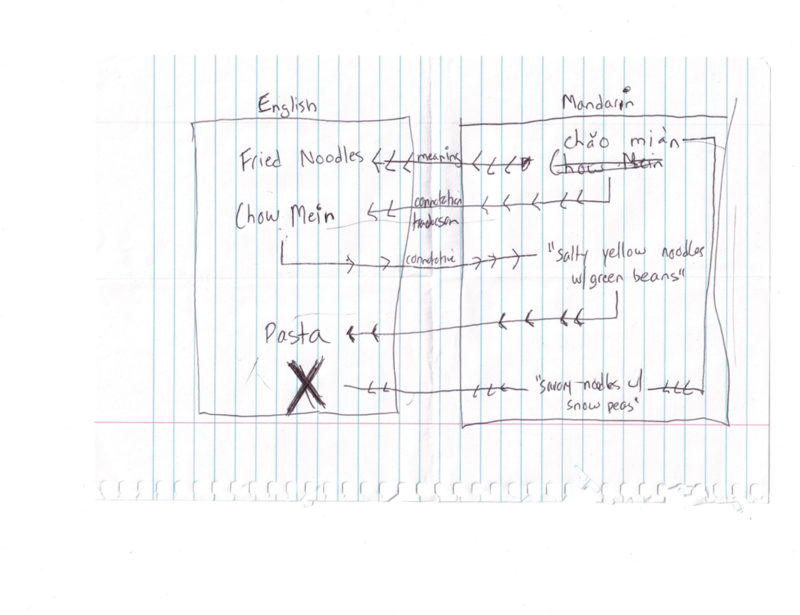

FW: We’re also thinking about meaning in terms of languages within a language. When you go into a professional social space, you’re bound to a meaning you can’t destroy because that’s what the social is founded on, so the destruction of language we’re doing is to peel back those pre-assumed layers of meaning and come out with new functions and new mutations of language.

BB: It’s unsettling our naturalized assumptions of what language is to us, that have been hammered into us—how inherited systems of representation operate on our abilities to conceive the world.

EW: An aspect of the group is breaking that language… bringing up all these contentions and points of tension we all have with language so that we as a group can rewrite or rebuild that language on a stronger foundation.

YC: Or to not need a foundation, to be able to work on shifting ground without having to pin anything down, not trying to establish common ground beforehand, but allowing the ground to grow common as it goes.

NH: The foundation is the collective.

YC: Improvisation is a key component of what we’re doing. If I say something nonsensical someone else can pick it up, and it reaches a new meaning—from wanting to understand what another person says, to be responsive.

NH: Yeah! And shedding reliance on stability and meaning that is often required to function in other circumstances. Within the group there is a comfort level that was achieved very quickly that really enabled the process of getting rid of—

FW: Pre-established meaning.

NH: Are those structures necessary here?

AX: How do we know that we’re doing the same thing? That we’re going about a collective methodology, for example, when we’re translating homophonically from Frisian? And to what extent is that relevant to what we are doing? Part of this exploration comes without any guarantee of what will be reached, and anyway we don’t seem very interested in the ending. Now was that because we always had a feeling, or is it a prelinguistic understanding, or…?

BB: Approaching life through translation, we’ve already found a way to accept divergence. Translation exercises isolate specific instances of rupture or failure in language. Our lack of desire towards an end goal helps us linger on breakages and play with them, incorporate them into the erotics of group expression—it doesn’t feel like we’re looking for something at the end of the day.

FW: If you have a goal in mind you’re setting out for a meaning you have to attain—that predetermines the process. What’s amazing about this group is that we can come up with the processes and just stay in the field of process that is the product.

YC: The risk is that it’s meaningless—I don’t mean that in a bad way—but we’re always at the edge of bullshit. I don’t know if you guys feel this way, but if I have to describe what we’re doing to other people I always feel like it’s kind of bullshit… but fertile.

NH: It’s true, I’ve tried to describe it to other people and I used generalities, like we “were on the island for a week and then we did something with language,” but to describe the process, you’re right, I don’t think you can without participating in it because it does seem a little bit like Wait what do you mean? What were you doing? That screams exclusivity though, which I don’t think we’re about.

AX: This highlights the participatory aspect of collectivity, which also extends to the audience. To be doing, to be talking, to be subject to listening is potentially always a collective idea given the actual physics of sonic reverberation which collapses the object/subject binary… Everyone is a listening subject, everything is subjectivized… There is an essential collectivity formed by listening which extends to everything indiscriminately.

EW: I think if I can manifesto-ize, I’d say that our project is anti-functionalist; what we’re trying to do is to prove to the outside, which hyper-emphasizes this idea of language as a practical means of achieving practical stuff, the possibility of dwelling within this liminal space of processes we’ve created. To reference Judith Butler, our goal is to make impossible formations possible.

NH: If we would have just gone to the island for a week, I don’t think we would have achieved the same kind of intimacy without the ideas and plans and texts, if we had just gone to hang out for a week… I think because we are dealing with language, meaning, and translation breaking down, that’s where a lot of the intimacy is coming from.

FW: It questions the minimal amount of rigor that we need because it’s not that we come from nothing…

BB: We have a framework for approach, a seminar and workshop format. Designated slots with aspiration towards improvisation or situational response… embrace of emergent qualities informed by the dynamics of expressing-together. Looking back at the mess, we could score our activity if we wanted, see where we went.

On Experimental…

YC: How do you not let experimentalism become normative as well? How do you not let being “outside of the box” become another box? It’s very hard to stay random and keep breaking the rules without rule-breaking becoming a norm in itself. Translation provides an opportunity to keep constantly moving things between spaces in order to refresh their strangeness.

BB: What do you call experimental? Who has historically been permitted entrance to the canon of the avant-garde, and who has been excluded for reasons that have nothing to do with the actual qualities of their work? When does it become only about the qualities?

FW: You’re talking about the avant-garde solidifying into an aesthetic movement.

YC: What’s the experimental, what does that mean?

AX: The experimental is always eyeing the limit, it’s an exploration of this limit, which can be a limit in itself. So I don’t know what the experimental part of our translation really is, which part is experimental—the fact that there is this relaxed rigour, or is it that we’re all living together? Which part of this is experimental? What does experimental really pertain to—the collective? The translation?

NH: I think yes to all of these things you mentioned.

FW: Bringing a bunch of strangers together—or semi-strangers together—is itself its own experiment.

NH: Knowing that we don’t know what’s going to come out of it?

YC: An experiment without a hypothesis.

NH: And without expected outcomes…back to process.

EW: I always read experimental as experiential, as the Toronto Experiential Collective.

On Islands…

AX: What do you think it is about islands that we like?

FW: They’re like the outside inside, outside of the city but not fully outside of civilization entirely.

NH: A bit of remove, a mythical island.

EW: It comes back to Homer, Ulysses… Robinson Crusoe… we’re all sort of our own Crusoes. It’s the I-sland becoming a We-land…

AX: I love to feel trapped with you.

FW: That’s another kind of limitation, a useful limitation to explore the boundaries of…

BB: The anticipation never really stops, there’s always the beginning of itself…

YC: On that note, I was thinking during all the time when we were all together that I had no desire at all to do my own work, do my own writing. I’m usually someone who is obsessed with getting shit done, but it felt like the work was being done in the moment. I had no eye for the future of my own personal projects of that kind.

EW: Your island turned to a We-land.

[All chant “We land We land We land”]

BB: I don’t want to retreat into my lair and focus on personal matters. The types of activities we do—that which we set out to do before we gather—morph when we get to it… and I feel like we are sensitive to each other’s states. Through the entactogenic de- and re- regulation of our states we were able to brush against attunement, sense how we were all feeling, what our capacities are, what could call an end to attention…

FW: Like hangovers…

BB: …and be willing to start fresh once we learned more about where we’re all at.

FW: I’m really interested in non-egocentric projects because I’m sick of the art world’s insistence on the I, the creator, the gallery show is my solo show, this book is published just by me… they’re always collective projects, but then you abstract from them an ego… It would be interesting to invite other people into the next residency and see what kind of reach we have when we’re not just a cloister, an insular six-person group…

[All chant: “And the six gives way to the eight…”]

AX: Do you believe we can create a shared language that is entirely intuitive—one that anybody can understand?

BB: The collective—that kind of arrangement, plus intuition, those two together make me think about affordance… activity growing more sensitive. The ways ecosystems respond to a stimulus and can incorporate that kind of newcomer, learn new behaviour…

NH: I don’t know if there’s any such thing as pure intuition that’s not informed by culture.

FW: At the same time there is no pure culture without intuition… I like the idea that we’re both Darwin and the Finches…the self-studying Finches.

EW: I think that division makes it so hard to think about the subject of the experiment.

NH: Part of the idea of the collective is to break down that division, that boundary.

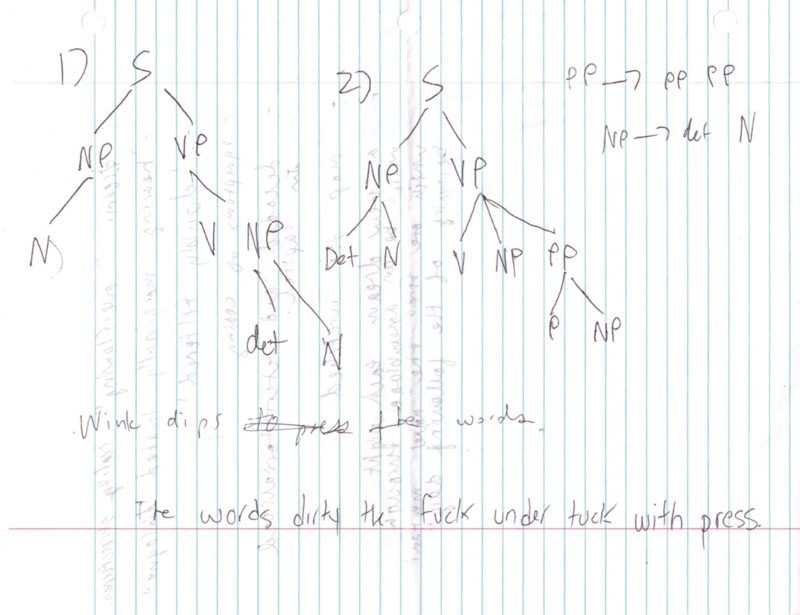

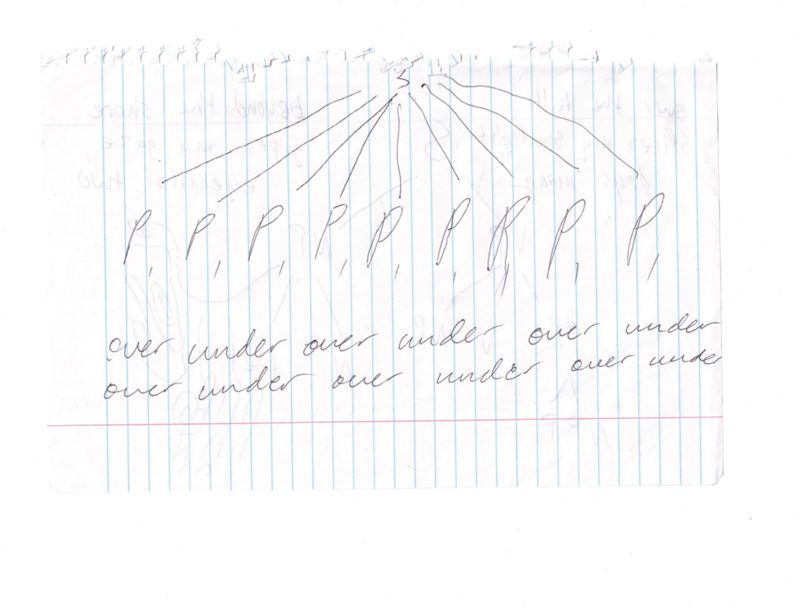

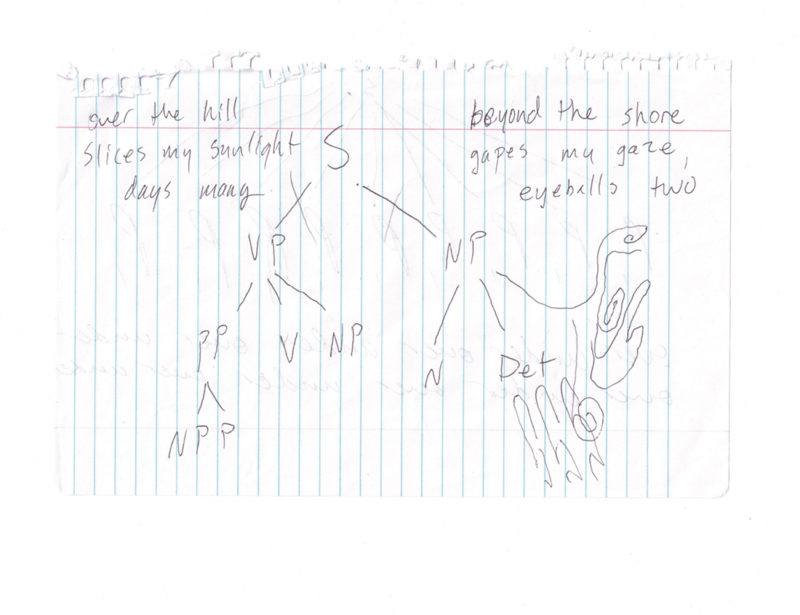

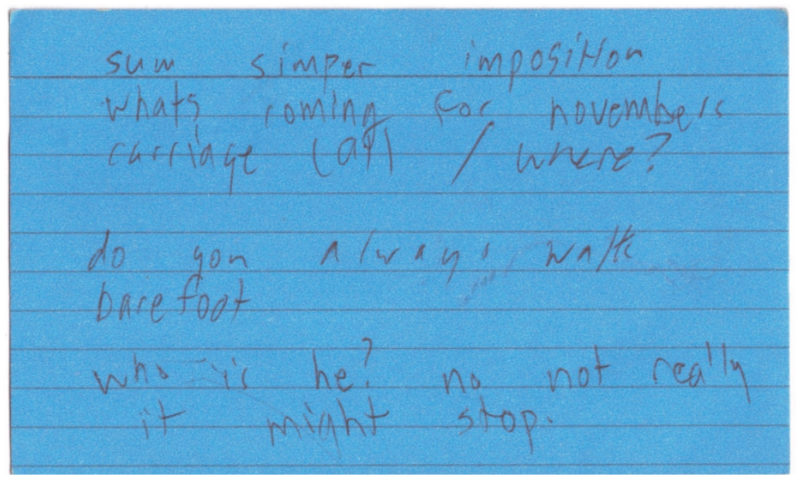

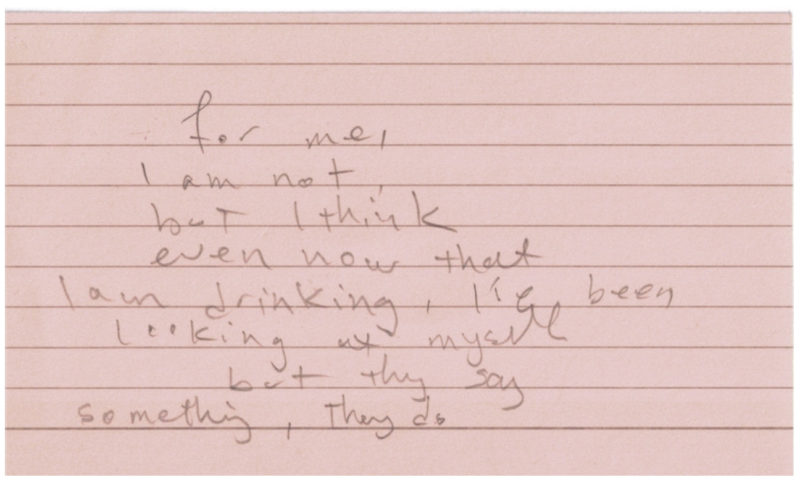

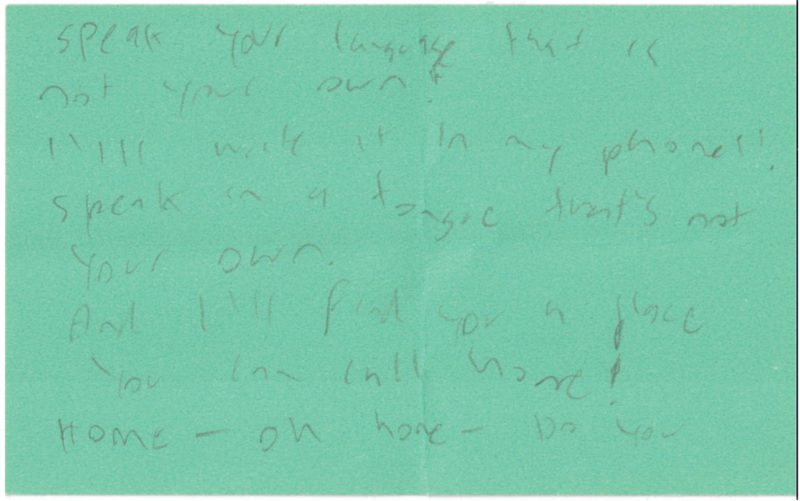

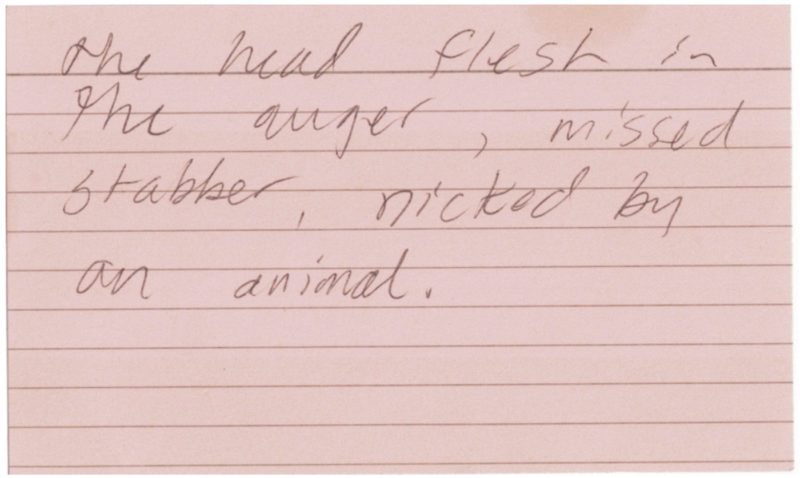

AX: What about the materiality of language? When we were on the pier and doing the transcription workshop*, we spoke of it as a sculptural practice. How does that play into what we’re doing? Writing, transcribing as a speech material? a speech trace?

[*Where we would stop and record everything we heard for seven minutes at a time, then perform the recordings in pairs, as dialogues in front of others.]

EW: We’re trying to capture something.

AX: By inscribing it? Is that what makes it material?

FW: Even the sonic recording of it, is a trace of the materiality of speech without transcribing it.

YC: We’re coming up against the material that’s left, when you’re transcribing you’re coming up against the limits of your body, your hand.

NH: Is speech a gestural material?

FW: Meanings are meaty.

EW: We’ve never eaten vegetarian.

BB: We’re carnivorous, come together to meet bodily. When that arrival is impossible, moving into recording and transcribing is a form of activity worthy of embrace. Cast off this half-measure approximating live performance and tinker with recordings that reflect the content.

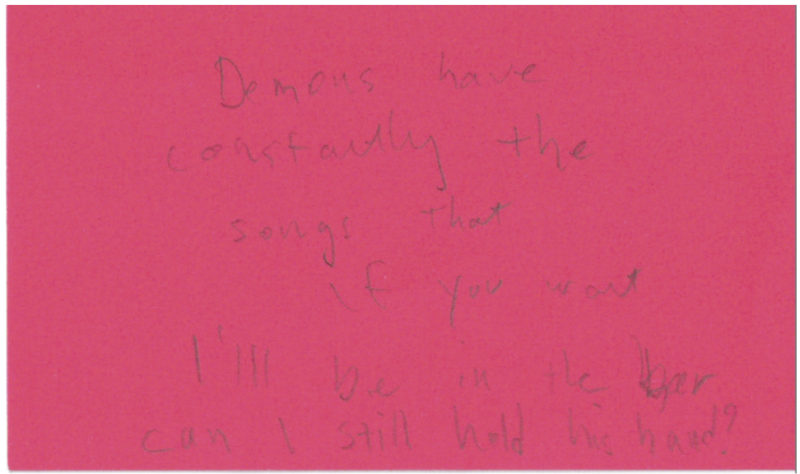

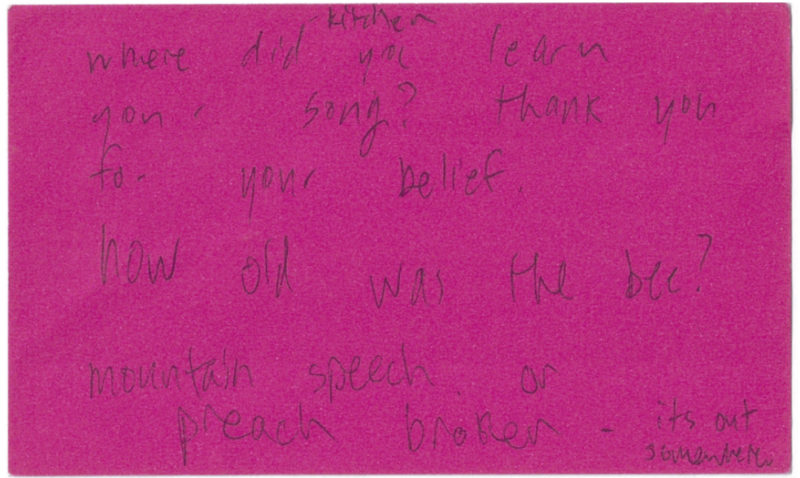

EW: I think it goes back to what the point of writing is, and it seems our activities always foreground this recording or this transcription in the very process itself. But in doing that, it opens a space so that our process can be radically open in ways we could never achieve if they were just kept purely transient. Whatever we’re doing will always be transcribed in us in the space of memory, but by actively writing it down we’re transcribing it to this external world as something which can be shared. We’re not necessarily seeing transcription as the product to be produced but as something our collective energies or ecosystems form. It’s a trace.

YC: In transcribing speech, what we’re doing is as much about what’s there as what’s not… the beauty of the real thing… recognizing that absence that we end up creating with… what’s lost is more poignant than what’s there…

FW: We’re not just trying to recreate what we heard or did.

YC: It’s impossible, the “event itself” is created retrospectively…

BB: A reason why I like the record: it can’t be read directly but through a needle.

EW: It’s a way of sublimating our desire to keep everything transient and egocentric from us by expelling it, barfing it out. Expulsion as opposed to keeping it in.

NH: We’re spectering, investing our desire for intimacy in the slippery spaces of meaning opened by collective translation.

AX: It’s like walking the circumference of the island, slowly.

NH: I like the metaphor of expulsion or excrement. In a way these traces, these archives, these documents are like a natural byproduct of our collective energies, because they’re never really planned in advance.

FW: The album is the first thing that we’re trying to do that is a product.

AX: How much will you sing on this album? What do you think singing has to do with translation?

BB: You can’t write singing; it doesn’t track the same, man.

YC: I think that singing adds an element to language that doesn’t need to be translated. You have the words that you are singing, but the way you sing them changes their meaning. Even if I don’t understand your language, I can understand something about the emotion based on the melody, the tonalities of the voice, etc. Someone singing a sad song might sound like they’re crying, someone singing about sex might sound like they’re moaning. Singing brings these non-linguistic forms of expression to speech and creates something that feels possibly more universal. Singing also feels more connected to the body than regular speech.

FW: In a way that simply mimicking crying or moaning can’t…

YC: And that goes towards our baby language as well.

AX: Open your mouth.

NH: What’s the relationship between mimesis and translation?

FW: A regular translation has an end goal where the process is subsumed under the end goal, which is to render a piece of one language into another…

AX: In mimesis there is an overlaying of representation on what is meant to be said, whereas in our translation the distance between representation and meaning is widened. We’re trying to achieve the greatest possible distance between the representation and—whatever is on the other side of that.

FW: It’s not predetermined, what’s on the other side of that.

AX: Which is what you said: mimesis’ end goal is teleological. It’s like a science experiment where the hypothesis already assumes the result.

EW: The objective of a scientific experiment is already decided. The first step of an experiment is making an ‘objective’ to prove as ‘objective.’ All translation is the translation of content as the end goal. But we are thinking, what does the translation of form mean? We’re always jumping between different forms, so that’s why we’re thinking of the record. And obviously we’re always trying to collide both form and content.

On Animals…

NH: Let’s go around and have everyone say their favourite animal.

AX: Walrus. Walruses are made up of 90% fat and they tickle each other all day.

NH: So you want to be a walrus?

FW: It’s a fetish animal…For me, the falcon.

AX: Ambitious!

FW: I love the way it interacts with humans. You can tame it as a falconer and it is never fully tamed. That’s sexy.

BB: I love worms and jellyfish.

EW: Jellyfish live forever, they get to a state and they de-age. Easy top two: turtles and donkeys. I was obsessed with all kinds of turtles, my video game screen names always had turtles in them.

AX: You have a turtle haircut. The shape of your face is very turtle-y.

FW: The shape of your face, the speed of your speech…eternal, ancient…

BB: I like bears… and their name is a funny translation, it’s euphemistic. I think the original name would invoke the bear, cause it to appear and wreak havoc on the settlement. So people would say “brown hair” in some proto-Indo-European tongue, or even go further and name it “honey-getter”, like with the Hungarian medve or Russian медведь. Had to get further and further away from talking about it directly—talk about it through its processes. They are great beasts.

NH: I oscillate between the fox and the ant.

EW: That sounds like a Joanna Newsom song.

AX: They’re both very noble.

NH: Really? The communal selflessness of the ant and the sly solitude of the fox.

EW: Do you think you’re hard working?

NH: Ant-like.

EW: Do you think you’re sly?

NH: If foxes are intelligent…

EW: I feel like you have a foxy smile.

YC: Pomegranate or persimmons.

Feature Image: Grave rubbing. All images and audio courtesy of the Toronto Experimental Translation Collective.