What Remains to be Seen: Gonzalo Reyes Rodríguez at Blinkers Art + Projects

23 September 2022

By Madeline Bogoch

There’s an obvious irony in the title of Gonzalo Reyes Rodríguez’s recent exhibition, New Photographs, which revolves around a pack of thirty-year-old photographs the artist acquired in Mexico City. Dated between 1987 and 1993, the photos depict a young, seemingly queer man who signed the backs with the enigmatic moniker, “Technoir.” The details of this opaque nickname are never revealed, and we are left to speculate on the meaning of this and other particulars through images of him amongst his friends, family, and lovers. What were initially intimate snapshots documenting a young man’s life have been reauthored by Rodríguez as cultural artifacts. The novelty alluded to in the title presumably refers to these shifting contexts, and the subsequent accumulation of meaning as the photos are subjected to the scrutiny of public viewership. Plastered in vinyl text alongside the photographs is an excerpt of an essay by author and curator Miwon Kwon, reflecting on the photo archive of the late artist Félix González-Torres. In this passage, Kwon remarks on the intimate familiarity we recognize in the images of others and how such images invite us, briefly, to inhabit them. New Photographs is designed to stage these very encounters, if only to underscore the failure of images to disclose the full picture.

Some of the photographs are collaged, casually askew, at odds with the orthogonal, viewfinder-esque lines on the canvas they are mounted upon. Others are superimposed over images sourced from the artist’s own archive. One such photograph, captured from a low angle, features our protagonist posing in a red silk robe as he caresses his chest. Rodríguez displays this photograph over an image of Michaelangelo’s marble sculpture, Dying Slave (1513–16). The two figures mirror one another, exuding a queer eroticism and spanning space and time in their representations of youth and beauty. In another photograph, “Technoir” appears alone, wearing a faded Madonna T-shirt and a deadpan expression. This pop-culture apparel acts as a wayfinder among the sparsity of contextual clues. Regardless of the significance of such details in the subject’s life, within the photo’s current environment they become a point of entry for the viewer to—as Kwon describes—occupy them.

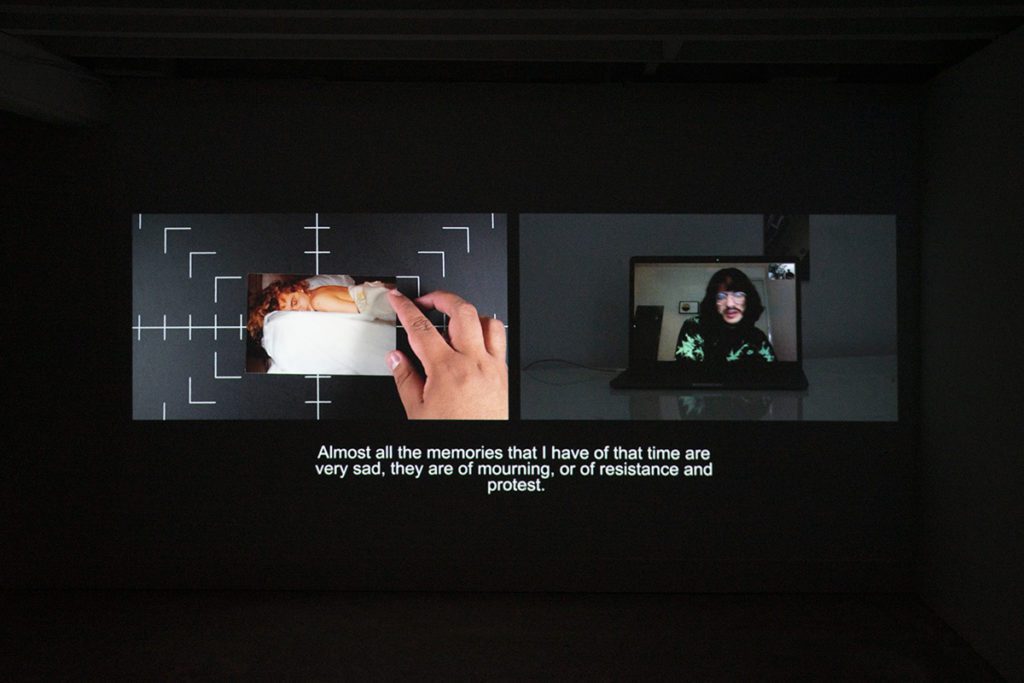

Rodríguez’s own speculation on the photographs remains conspicuously absent from the show. A video diptych displayed in the exhibition shows the found photographs in one screen, while colleagues of the artist analyze them in the other. Rodríguez remains mostly silent during these analyses, occasionally chiming in, but mainly relies on his colleagues, and the viewers, to be proxies for his speculation. One of Rodríguez’s commentators approaches the photographs with a more qualitative method, translating the inscriptions on the back and only cautiously parsing signs of privilege and queerness. In contrast, the other commentator fashions bold speculations on the personal life of the subject, particularly on his sexuality and relationships with both the men and women featured in the photographs, declaring at the outset of the video that “faggotry surrounds him.” The inclusion of the video in New Photographs adds a sense of dynamic exposition to the work as the viewer forms their conjecture in real-time alongside Rodríguez and his associates. The narratives offered by the artist’s friends never quite cohere. Although photography as a medium has often been defined by its ostensible objectivity, the ambiguous nature of New Photographs reminds the viewer that images often contain multiple and conflicting histories.

The potential of photographs to signal beyond that which is shown in the frame is highlighted by the artist and his collaborators’ readings, which further connect the scenes depicted to the particular cultural context in which they were taken. Remarking on a carefree attitude evoked in the snapshots, one of Rodríguez’s friends wonders aloud about what, if any, was the subject’s connection to the AIDS crisis. It’s a historical flashpoint that is evoked not through any explicit reference, but as an omnipresent shadow lurking over the queer experience of the late 20th century. As is noted by Rodríguez’s colleague: “all of my memories of that time are of mourning, resistance, and protest.” The absence of these ubiquitous markers becomes a noteworthy element in New Photographs. It’s an allusion that ties back to the text by Kwon, written sometime after González Torres’ death of AIDS-related illness. The spectre of the AIDS crisis, in both instances, illustrates how social memory is constructed in hindsight through images which may or may not prove to be reliable witnesses.

In the absence of substantial evidence, these assumptions are loaded with the baggage of the viewer’s gaze and experience. The nature of our proclivity to project, and the implication of doing so, is the thematic heart of New Photographs. A 2019 article by author Zadie Smith, titled “Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction,” makes a compelling claim for the prerogative of writers to cross identity lines while crafting characters.1 For Smith, this is a practice worth defending, even as she acknowledges the risk of misrepresentation. I tend to agree with Smith, but it’s easy to imagine how such a position could be hijacked in bad faith to cover for the unilateral entitlement over the lives and experiences of marginalized subjects. While both images and fiction invite the viewer to imagine beyond one’s own subjectivity, the desire to do so does not mitigate the limitations of embodied experience. Nor is this exercise a neutral one, as even when undertaken with the best of intentions, projections such as these are easily contaminated by preconditioned bias. It’s a dilemma that is wisely left unresolved in New Photographs. Instead, Rodríguez leaves us to dwell in the ambiguous pleasures and ethics of occupying the images of others.

- Zadie Smith, “Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction,” The New York Review, October 24, 2019, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2019/10/24/zadie-smith-in-defense-of-fiction/.

New Photographs ran from October 22 – December 31, 2021 at Blinkers Art + Projects in Winnipeg, MB.

Feature Image: Still from Portrait: Tech Noir 2021 by Gonzalo Reyes Rodríguez. Photo courtesy of Blinkers Art + Projects.