“Felt Good, Everyone Knows It”

3 April 2021

By Megan Gnanasihamany

Let’s pretend that we’re at a show. It’s sometime before last March, any night of the week. Early evening, but this is winter, and the sun has been set for hours already. We shrug our coats off into the all-black pile. I’ll retrieve mine later to wear it loose over my shoulders, following the smokers outside to revel in the cold between sweaty sets, after which I’ll fix my wandering eyeliner in my front-facing camera, since the available bathroom is the one with no mirror. You grab a water, maybe a beer, from the bar or your bag, depending on where we are. The night is full and warm and easy, and we maneuver through friends and strangers, angling for the right spot from which to watch other friends on stage. Then it’s your turn to go up, and the roles reverse.

To start with the performance is a false beginning, though. There are months of creating, collaborating, practicing, throwing everything away, starting over, and practicing over and over again to account for—hours of means leading to an end—in the form of the show. Since March of last year, there has been a lack of available endings. All the regular DIY deadlines of music communities—shows, tours, events—have been on indefinite hiatus without meaningful predictions for when gathering in poorly ventilated basements and bars again will no longer be a risk to public health. As the isolating conditions of a mis-managed crisis bleed into 2021, artists and musicians who rely on collective spaces are left to hang out in an ongoing period of stasis—a temporal waiting room on annual renewal, no end in sight.

DEMO FEST, which launched on December 21, 2020, started out as a deadline. It was DEMO FEST coordinator Martin Tensions’ response to the motivationless void of a pandemic summer: a songwriting challenge among bandmates and friends with a set date, by which something, anything, had to be finished. Set within the potentially borderless networks of the Internet, the project expanded. The team behind last year’s I Can’t Believe It’s Not Paris festival joined in the coordination effort, and registration for Demo Fest opened in September with a decidedly DIY website aesthetic and a Google form sign-up link. Participants committed to spend the fall writing and recording a demo, the first release of a new project or band, which would be released on the winter solstice. Over 350 projects registered, 202 of which resulted in a submitted demo, available as of December 21 on the DEMO FEST Bandcamp with proceeds from the Bandcamp sales going to support Solidarity Across Borders, a migrant justice network member which has been organizing for status for all since 2003. Through the efforts of a small team of collaborators in the Montreal punk scene, DEMO FEST turned to old school fundraising methods, retrofitted for the interconnected world of digital livestreams and instantaneous updates across networks. From dusk on the evening of the winter solstice to dawn on December 22, a live steamed telethon played a single track from each project. Music and videos were interspersed with updates from the organizers on the fundraising numbers which climbed through the night, presented through hand lettered signs held up to the camera. Accompanying the stream was a live chat and the DEMO FEST Instagram story, a series of updates from international viewers tuning in to the stream from homes and backyards. In my living room in Montreal, my roommates and I projected the stream on our wall and logged into the chat from our phones and computers, writing reminders of tracks to download later by donation. Washed in the blue of multiple screens, we were teens of the 2000s again, at a party through the magic of AOL and MSN Messenger, together in the late night with Internet access.

Somewhere in the middle of the 5th or 6th hour of the stream, I wrote down Tracheal Shave’s track, “They put a claire’s in the walmart”, a giddy and inarguable 49 seconds of cybergrind (a genre meld of electronic music and grindcore) appreciation for the accessible princess aesthetic that Claire’s, a tween-girl-centred accessories outlet, provides. Over video chat a couple weeks later, Bailey, one half of Tracheal Shave, describes the solstice telethon as “definitely the closest I’ve felt to being at a show”. She and her bandmate, Terra, spent the night around a fire in Asheville, North Carolina, watching the stream with friends on a projection against the side of a house, 1600 km south of where my roommates and I were viewing the same stream. For Bailey and Terra, DEMO FEST offered an opportunity to finally collaborate under a name they had come up with years ago, but never had a chance to use in the four years that they have been playing together in the hardcore band, CloudGayzer. Bailey and Terra live close to each other, and called in to talk about Tracheal Shave from Bailey’s room where they wrote and recorded the four tracks that make up their demo, “Gimme Sugar!”. Laughing, Terra describes writing lyrics through a process of riffing outloud line by line, midway through recording, coming up with lines like “I want to go to Claire’s” and adapting to the technical challenges of home recording right down to the submission deadline. “We kept saying ‘don’t think about it too much’”, “if you think about it too much it doesn’t count”— for a deadline to work, it has to eliminate the allure of caving to perfectionism, which abandons work unfinished and unshared in the recesses of harddrives and software storage. As 200 + friends and strangers submitted their demos for the opportunity to raise funds for migrant justice, DEMO FEST created a deadline of accountability, one worth putting effort into thinking less, and doing more.

Julio Prato and Ben Osbourne of 19 Names in a Plastic Cup echo Tracheal Shave’s “don’t think” ethos. Together with Simone Sparks and Violet Hennessy, they are four of the eighteen members of 19 Names in a Plastic Cup. The project is exactly what it sounds like: through the laws of chance as determined by slips of paper in a cup, members of the St. Louis, Missouri DIY music community were shuffled into five new bands, each of whom recorded one track for their collective demo, “1955”. Five weeks before the submission deadline, Simone came up with the idea for a band lottery; longtime collaborators were split up and paired off with first-time musicians. Multiple members of the project rotated between instruments, picking up new ones as needed in order to round out the sound of each track—it is this that accounts for the fact that none of the bands ended up as three bassists collaborating in a Google Drive file or a vocalist-drum-machine quartet. For participants like Violet, who had never played in a band before, 19 Names created a structure of support and mentorship, facilitating the first songwriting experience for some, while requiring a shift to set patterns of production for others. Like a matryoshka doll of music making, each individual track on “1955” emerged from a process of experimentation and care as intensive as corralling 18 different collaborators into a single demo—there’s the improvisational take on a conversation, a surprise Vincent Price sample on track five (while two the original list of twenty ended up having to drop out, there are nineteen names on the demo if you count Price). “It [made] us all responsible for people we don’t really know”, says Ben, describing the dynamic of working with bandmates he had never met. The sentiment still holds true for the project as a whole, as the potential of raising funds for migrant justice served as further motivation to finish the collective effort.

In St. Louis, locals-only shows are always fundraisers. As of January 31, 2021, DEMO FEST had raised over $10,000.00, a locals-only show for anyone who registered or tuned in. There’s an early web optimism to the image of the Internet as a digital commons. The fantasy of fully automated techno-utopia pictures us tuning into a global offering of social and cultural stimuli, all available through the life-changing magic of logging on. This dream of online living expands the concept of “local” to encompass anyone with wifi and a smartphone, but the border-free digital zone is also a ghost world, disconnected from the just future that alliances like Solidarity Across Borders are organizing towards. In Gore Capitalism, Sayak Valencia, a Tijuana activist and intellectual, examines the economic, political, and social zones that are formed by borders, establishing the limit to which expansive, digital spaces can meaningfully counter both borders and long-distance socialization. From Gore Capitalism,

“It’s important to emphasize that the marriage of economics, politics, and globalization popularizes the use of new technologies, under the guise of eliminating borders and shortening distances, even if only virtually. But the goal of this marriage is the creation of an uncritical and hyper consumerist social consciousness that rolls out the red carpet for overt systems of control and surveillance. The existence of these systems is thought to be logical, acceptable and demanded by society itself, thus transgressing and re-conditioning any notion of privacy or freedom and shaping a new idea of personal, national, and social identity. The contemporary idea of the social can be understood as a conglomeration of autonomous individuals who share a determined space and time and who participate (actively or passively (and to varying degrees) in a culture of hyperconsumption.” (1)

The Internet allows for a minor miracle of bilocation—I am in my living room, holding my phone 6 inches from my face, I am with you in yours, and we’re both in a studio in Montreal, watching a livestream in progress—but, our connections come courtesy of corporate actors including Facebook, Instagram, Google, and Zoom. Since last spring, even my neighbours have become long distance relationships. Aside from the occasional run-in on the front stairs, we chat through text, message each other on apps, and watch each others’ stories to make it seem like we still live in close proximity.

Lees Brenson lives four blocks away from me, and until last summer she was my downstairs neighbour in our Plateau walk-up. My cat used to go on fieldtrips to Lees’ to scare off unseen mice who were nesting in the walls. During the fall, there were at least five DEMO FEST projects in progress between our two apartments. Lees and her bandmate, Anastasia Westcott, are HRT, and we spoke on video a couple days after the winter solstice launch. I’ve watched Lees and Anastasia perform multiple times over the last few years in Montreal, and there is a much stranger disconnect in video-calling someone who you’ve seen scream into a mic through a fog machine from three feet away than there is to calling up bands in America. Anastasia spent the fall in a good-screen-bad-screen tradeoff, following twelve hour days in online school with a video call to Lees to collaborate on their demo, “Warm, Wet Stroke of Luck”. For all that screen overload though, she describes the chat during the livestream as “lifegiving”. “The livestream was definitely one of the nicest things that’s happened in a long time for me” she says, and Lees agrees. For all the hell that the Internet offers and traffics in, without safe options for being together in person, chatting under a screen name while a homemade greenscreen music video plays feels incredibly close to the utopian fantasy of collective, online life. Significantly, the DEMO FEST live stream was hosted by Suoni Per Il Popolo, a nonprofit experimental music festival presented by the Société des Arts Libres et Actuels (SALA), which has been hosting free live-streamed shows and events since it became clear that in-person festivals weren’t going to be a feature of the Montreal summer. Suoni, unlike Youtube or Facebook live streams, doesn’t have ads or sponsored links lining the stream window. Participating in the livestream, we were the “autonomous individuals who share a determined space and time” that Valencia describes. The only consumption we were incentivized towards was the purchase of DIY music, funnelling funds towards the abolition of borders.

Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz describes the “punk rock commons” as a collectivity organized around “the desire, indeed the demand, for ‘something else’ that is not the holding pattern of a devastated present, with its limits and impasses. This demand is for a dystopia that functions like the utopian”. (2) Muñoz identifies a specific “something else” in the sweaty exchange of touch and performance in the Los Angeles punk scene of the 1980s, but it also exists generally in the emphasis on creation over profit, in the DIY and esteemed amateurism of punk ethos, and in the negation of hegemonic structures of value like the accumulation of wealth and property. On utopia, Muñoz writes that “[it] is an ideal, something that should mobilize us, push us forward. Utopia is not prescriptive; it renders potential blueprints of a world not quite here, a horizon of possibility, not a fixed schema”. (3) Organizing and activist work is always, in a sense, speculative. It relies on an as-yet-unrealized world, but one that can be brought closer to reality through the work of living that future’s ideals and values everyday, in our here and now. The world that Solidarity Across Borders is fighting for is one of “open borders and the free movement of people seeking justice and dignity, meaning freedom to move, freedom to return, and the freedom to stay”. (4) They organize towards a visible horizon that’s made solid and approachable through demonstrations, petitions, direct action, and mutual aid fundraising to cover the immediate needs of non-status migrants such as food, rent, and phone bills. In forming DEMO FEST as a participant in the fight for this future, the digital space that the fest utilizes becomes an Internet ‘something else’: a someplace else dedicated to a break with the hyper consumerist and heavily-policed present that national and international borders contain.

If DEMO FEST can be seen as an embodiment of Muñoz’s punk rock commons, the project that marks the closest approach to a utopian something else is Tender Fruit Industry. Produced by Kit Andres, the demo is a collaborative effort between Kit and their neighbours, migrant farm workers in Ontario who Kit lives alongside and organizes with, through Migrants Rights Network, a national alliance of refugees and migrants together with their supporters and allies. I call them on the phone to talk, their rural internet being not up to the task of facilitating the face-to-face simulacra of a video call. Tender Fruit Industry is Kit’s first musical project in about ten years. We share a similar background in music, having both spent years in the Royal Conservatory music education program— a stunningly uninspirational experience (I passed the last exam that I took, Royal Conservatory piano grade five, with a 51% and quit playing piano for years after). When they moved into their current neighbourhood, Kit took up one the instruments they had played in highschool, playing drums for local church services and meeting the migrant farm workers who made up the congregation. The trust they built in playing music – showing up regularly as a member of the community – became the basis of their relationships with their neighbours, leading to conversations about the music everyone listened to back home. In the fall, one of the workers they organize with, Saint, shared a clip of himself rapping about permanent status while driving a tractor. “This could be our theme song” he said, and Kit, witnessing a work that required an audience, registered for DEMO FEST. The Tender Fruit Industry demo plays like the backing track to a liberatory movement. Speeches and chants from individual workers and organized actions are layered over digital compositions that Kit says were written to reflect the emotional tone of a year of both great organizing victories, realizing hopes for a more free future, and continued injustices levelled onto those like migrant workers who are subject to state-sanctioned mechanisms of control and isolation, exacerbated by the pandemic response. Two minutes into the second track, “We Want it Now”, there’s an almost hyper-pop turn, a tonal shift reflected by their process of songwriting— “[I thought,] what soundtrack would I want playing in a getaway car?”

In the charitable model of aid favoured by foundations and nonprofit organizations, aid is issued unidirectionally. Campaigns emphasize (small) sacrifices in the name of charitable giving, denying recipients their positions as valuable and beloved members of communities who give and receive to each other in equal measure. For Kit, the live stream and chat offered an opportunity to reconnect with friends in Montreal, separated by distance and the impossibility of safe travel, but it was also an example of the ways in which DEMO FEST operated as an alternative model of aid, based in community care. “To see people typing ‘STATUS FOR ALL’ in the chat, … then I can go back to Brother C and the Steel Road [Freedom Fighters] and say ‘you have so much support, there are weirdo punks in Vancouver and Montreal who are behind you 100%, and they’re using their art”.

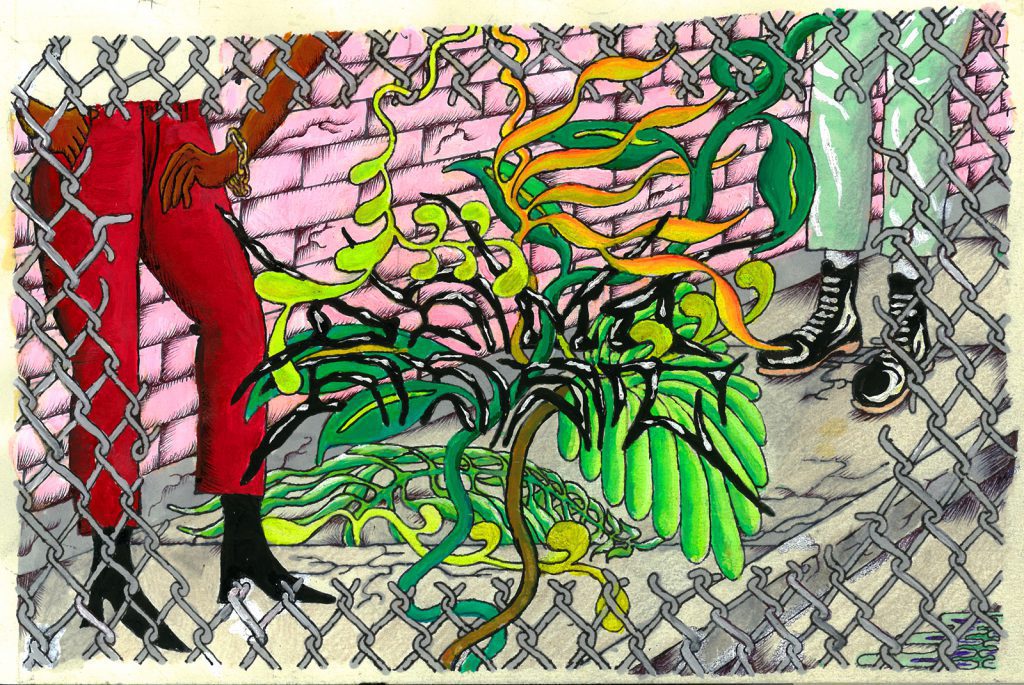

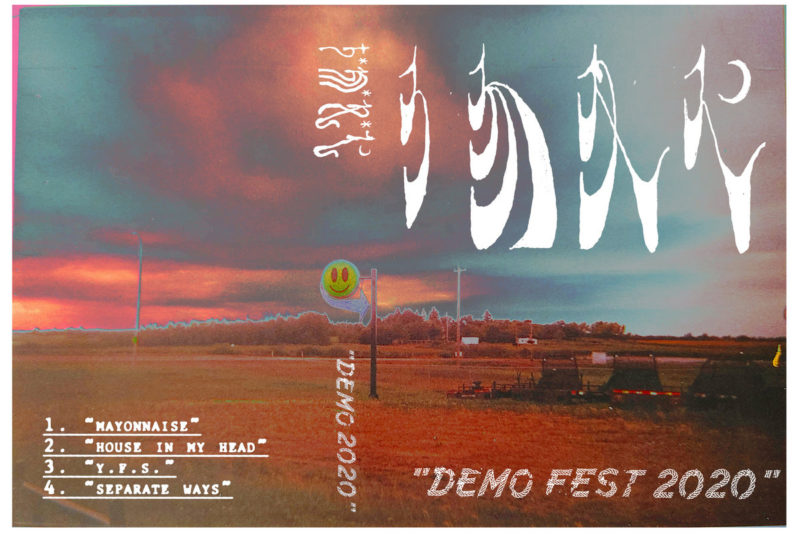

Throughout the various collaborations of DEMO FEST, there are interconnected loops of giving and receiving. From the workers of Tender Fruit Industry supporting other migrants, to the comfortable opening for new musicians set up by 19 Names in a Plastic Cup, there is an emotional resonance of generosity iterated between the participants whose efforts were in support of Solidarity Across Borders. Lees of HRT describes the connective feeling of learning a new skill alongside so many others who were using new instruments and exploring methods of working over the internet for the first time as part of DEMO FEST. Using Zoom as their shared studio, the HRT demo was made through a process of call and response teaching, as Anastasia taught Lees how to write and record with an analog synth for the first time. Any project could opt-in to free mastering by Will Killingsworth of Dead Air Studios in Western Massachusetts, and when the DEMO FEST newsletter delivered the news that projects without cover art would be given a simple, placeholder image, Jane Harms jumped in to offer custom art. Jane was already a part of the fest, working with her friend and collaborator of over seven years, Steve Believe, on Heal. The resulting demo is sharp and beautiful, reflecting the bandmates’ long term commitment to their friendship and shared creative projects. The cover is a photo Steve took at the intersection of highways 13 and 21, outside of Camrose, Alberta, eerily edited by Jane to appear outside of time, as though a warm and welcoming halogen glow were transposed across the prairie landscape. In total, Jane ended up receiving ten requests for cover art outside of her own project. Some projects, like 19 Names in a Plastic Cup, came with minimal instruction and no music to draw from; others sent their demo and a description or requested direction. Scrolling through the DEMO FEST Bandcamp, it’s easy to pick out Jane’s covers. With signature linework and a level of detail that belays the tight time frame they were created in, the covers exemplify Kit’s description of DEMO FEST: “it’s people putting work in willingly and joyfully”, labouring together to share in the creation of a blueprint for the different, better world.

Among the 202 demos available by donation on the DEMO FEST Bandcamp, I am in good company. In the middle of the night, somewhere between the December 1st deadline and the morning of the following day, I submitted my demo too. At twenty minutes in a single track, it’s more of a reading than a music project, but I agree with Julio of 19 Names—the ability to participate in the fundraising towards Solidarity Across Borders’ mutual aid fund far outweighs any uncertainty about the merit of one, individual project. Still, I had been hesitant about participating at all. I had written music only once before as a nine year old in the second of what would become a decade of mediocre efforts in Royal Conservatory piano. The piece was a one minute solo called “Little Bird”, the notes coloured in with pencil on a single page of sheet music. My career in composition finished approximately a week after the piece was written, as I discovered during my weekly lesson that just because I had written the piece didn’t mean I was released from practicing.

While a lack of compensation, time, and resources has always made art-making hard for those of us without generational wealth as an income stream, the prospect of another long year without shows, galleries, performances, or shared creative spaces adds as extra dose of “what is the point” to the consideration that comes before starting any creative endeavor. For me, part of the point of making art has always been that someone else will see or hear it, that there is some possibility that another person will encounter some true part of what I’ve tried to express and find that it relates to them too. Without the physical world to move through, Internet platforms like DEMO FEST offer the best shot at meeting a new horizon, and of expanding beyond it—making the work of creating, collaborating, practicing, throwing everything away, starting over, and practicing again—a coming ‘something else’. The present contains borders, policing, and prisons. The future doesn’t have to. As a “punk rock commons”, DEMO FEST fomented a small utopia. Through online channels and one deeply chaotic group chat, we were able to briefly reside in a world in which we can dedicate labour, “willingly and joyfully”, in order to provide art and material support to a broad community, built on the bonds of solidarity. The not yet realized world edges closer.

So, let’s pretend we’re back at the show. It’s sometime in the future, any day of the week. The lineup is a mix of friends and friends-of-friends, strangers who will be sleeping on our couches and floors later tonight. The visiting bands drove in from other time zones, crossing no borders or checkpoints along the way, moving freely across what used to be a country or a state. I lean over to whisper in your ear, but you can’t hear me over the bass—the show has already started.

- Sayak Valencia. Gore Capitalism, 43.

- Muñoz. “Gimme Gimme This… Gimme Gimme That”: Annihilation and Innovation in the Punk Rock Commons, 98.

- José Esteban Muñoz. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 97.

- https://www.solidarityacrossborders.org/en/a-propos/our-principles

19 Names in a Plastic Cup

To submit your name to future interactions of The Cup, you can email Simone at: demolottostl@gmail.com

DEMO FEST launched on December 21, 2020 in Montreal, QC.

Feature Image: DEMO FEST Card, by Jane Harms. Photo courtesy of the artist.