A Correspondence on ‘Memory Palace’ at Franz Kaka

23 March 2021

By Parker Kay and Madeleine Taurins

Thursday, September 10, 2020:

Robin Cameron’s solo exhibition titled Memory Palace opens at Franz Kaka’s new location at 1485 Dupont Street.

Sunday, September 13, 2020:

Parker,

We were both headed to see Robin Cameron’s exhibit Memory Palace. I was walking, you were riding your bike. We had apparently chosen the same route, only different methods of transportation. I had turned around halfway because a few seconds earlier I realized that it was Sunday, not Saturday, and the gallery would be closed. As I turned, we crossed paths–you headed where I was just a few seconds ago. Now that I was turned in the direction of my house, changing directions again seemed like too much change for one day. You continued on, risking the possibility that you would show up and there would be no one to let you in, but there was. You saw the exhibition that day, a Sunday. I did not. You sent me a picture of the show and I regretted not turning a second time, back in the direction of the destination I never made it to.

Wednesday, September 16, 2020:

Madeleine,

It’s funny how selective memory can be. I remember biking up Symington Avenue on my way to see if I could get a peek at Franz Kaka’s new space. When I saw you from a distance I didn’t know it was you per se but I instinctively felt you were someone I knew. As I got closer and realized it was in fact you—Madeleine—I remember feeling as if you thought I was an approaching stranger. I pushed through my insecurities, and the oncoming wind, to get your attention.

My recollection was that we had met before you had made the decision to turn around and head home. I even remember us discussing that it was unlikely the gallery would be open—it was Sunday after all—but after reading your message maybe I fabricated the moment entirely. The result we agree on: you decided to head home and I blindly continued north. I didn’t know exactly where I was going but I knew that the address was 1-4-8-5 Dupont St. To my surprise I found my way inside the winding halls of the Clock Factory building before eventually finding the correct unit on the second floor indicated by a sign on the door. A wash of blue dominated my vision as I entered Robin Cameron’s Memory Palace. When I think back to the blue, I don’t think about the blue wall facing the door, but blueness itself. You and I exchanged texts shortly after I arrived and I sent you a photo of my blue point of view from the door.

Saturday, September 19, 2020:

Parker,

I keep forgetting about the blueness of the room, which is odd because I usually cling pretty hard to the memory of blue things. I think it’s because when I constructed an image of the space in my mind, there was no blue wall. An ‘image’ isn’t exactly the right word, though. What I had in my mind were objects drifting in a kind of blank space. And they were mixed up with other objects I had seen before, like a page of Google images, but less organized and less square.

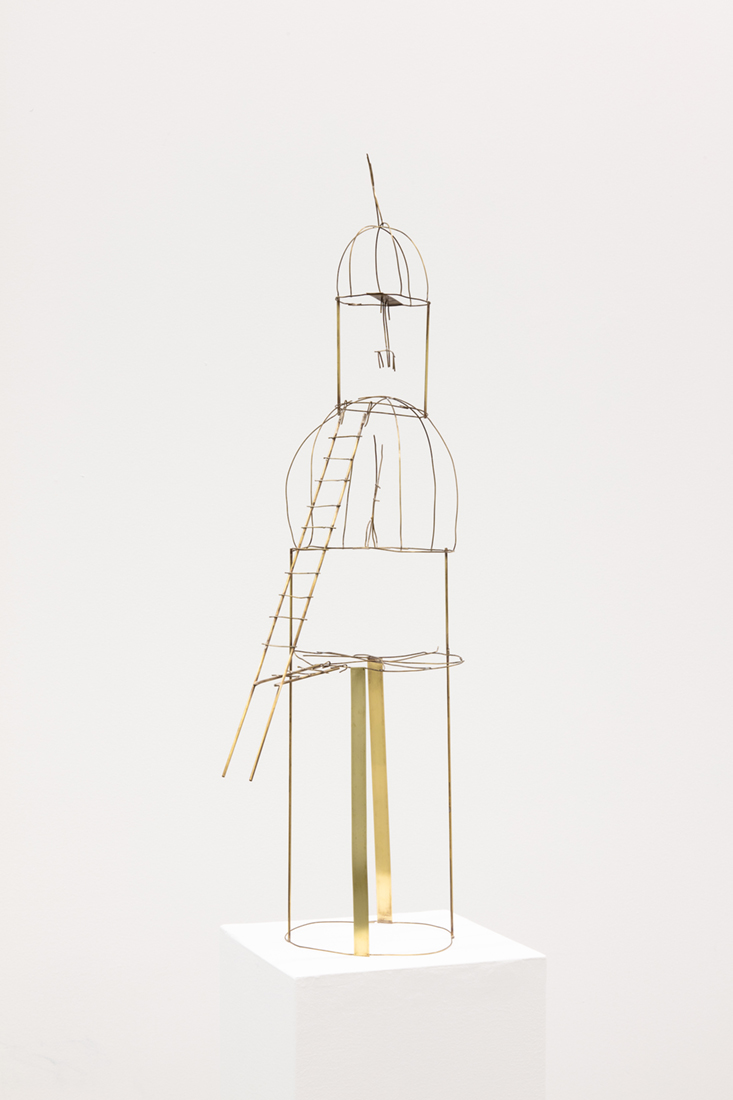

I had already seen a photo of one of Cameron’s brass sculptures. So thin and teetering, it looked like the steeple of a palace drawn by a child in the air. A tiny ladder crossed through the middle of it, leading nowhere but through. At the top, the whole sculpture bent towards itself in a kind of curtsy. It reminded me of brass sculptures by Fausto Melotti which are similarly delicate and made of curious shapes that feel familiar, like a forgotten but comforting language.

I first encountered Melotti’s sculptures while working at a gallery exhibiting his work. They were displayed on these plinths that consumed most of the floor, and you had to walk through a carved out path between them that curved through the gallery. It was designed to mimic Alberto Burri’s “Grande Cretto,” a massive concrete landscape built on the ruins of a Sicilian town called Gibellina that was devastated by an earthquake in 1968. From an aerial view, the town now looks like one of Burri’s famous paintings, lying like a giant between green hills.

So these were the images—Melotti’s sculptures, an Italian town made of concrete paths, and what I had already seen of Cameron’s work—floating in my mind when you sent me a photo of the actual exhibit, and these were the images I brought with me, still floating around, when I saw the show myself.

Monday, September 21, 2020:

Madeleine,

It’s interesting how things can be reverse engineered. The grid of Google images becomes a way of describing the process of recalling mental images when one could imagine this being the exact rationale for the design choice to begin with. A veritable virtual version of Ezra Pound’s Phanopoeia—a projection of images onto consciousness.

Less organized and less square feels a lot more like memory for me, too. In construction terms, whether or not two walls are square determines the success or failure of the structure. In the majority of situations we are locked to right angles (90 degrees) and I suppose if an angle is not right then it is wrong. Another way a builder might describe this is that a “true” corner would be squared to exactly 90 degrees. A-ha! All of a sudden there is a correlation between trueness and squareness in space. When we think about memory in spatial terms—perhaps one of the main conceits of Cameron’s exhibition—it feels like we can challenge these rigid definitions and alter our own realities. Cameron uses rough hatching in her prints to evoke how out of square or untrue the process of recollection can be. The addition of colour, irregular and quick, reminds me of how it feels to reassemble a dream after waking up. How do we even factor in trueness or truth into memory? As we learned from our separate descriptions of our meeting on the street, memory often sabotages the idea of objective truth.

Your descriptions of Cameron’s brass sculptures are apt. Thin, teetering, and definitely not built on right angles. To me they appeared as ruins from a different realm, or alternate universe, where the laws of physics are only limited by our imagination. Immediately upon seeing them for the first time, Cameron’s sculptures reminded me of Tatlin’s Tower. Svetlana Boym describes how ruins not only indicate a past that once was but also a future that could have been. Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919-1925), aka ‘Tatlin’s Tower’, was designed to defy the “bourgeois” Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, and even gravity itself. Tatlin’s tower embodied radical anti-monumentality and a revolutionary spirit against the status quo. The fact that Tatlin’s Tower was never built keeps it in the realm of potential where its ideological and structural rebellion can live on forever. I wasn’t familiar with Melloti’s work until you mentioned it, but his sculptures definitely would fit in a room with Cameron’s steeples and Tatlin’s Tower. I’m looking at an image of Melotti’s Rondò delle idee galanti (1981) and I feel the same excitement as I do with Cameron and Tatlin: the work is revealing an entire world to me, while also being on the verge of utter collapse. This tension is a lot for my eyes to feast on.

I should make some dinner.

Thursday, September 24, 2020:

Parker,

You say that because Tatlin’s Tower was never built it retains its intended —and perhaps impossible—purpose, suggesting that through physical realization things will inevitably be lost. This allure of the unrealized is also, I think, connected to memory.

Recollection is a lot like building something. Parts fall away in the process. In taking shape, whether it be the shape of letters forming a word, or the shape of your tongue forming a sound, the recalled thing becomes both more concrete and more unstable: concrete, because suddenly it can be witnessed; unstable, because with witnesses come the interpretations of other eyes, hands, and tongues.

Looking at one of the prints (Memory Palace (Lobby), 2019) in Cameron’s exhibition, I recognize the ceiling of the old Whitney Museum (later, the Met Breuer) and I feel, strangely, proud…Like I’ve said a word at the exact same time as someone else. Jinx! How pleasing it is to feel connected to things—how easy it is to please us! Within this series appear real places, artworks by Cameron, artworks by other artists, and unfamiliar objects like clues on a map. The more I get to know her work, the more things I can point out, and every time I do, it feels like I’ve run into an old friend in an unfamiliar country.

Patches of colour hover over the lines in Cameron’s prints and feel like floaters in my eyes, like I could blink them away. In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard writes, “The color-patches of vision part, shift, and reform as I move through space in time. The present is the object of vision, and what I see before me at any given second is a full field of color patches scattered just so. The configuration will never be repeated.” (1) Cameron combines two print-making techniques: intaglio and watercolour monotype. Her configurations repeat but never in the same way. They’re all there in the process, the things lost and gained in recollection, when the press rolls over the plate. The roundness of memory, you might say.

What did you make for dinner?

Monday, September 28, 2020:

Madeleine,

Those moments when memory is confirmed by another person are so gratifying. I’m not crazy, after all! The Mandela Effect, on the other hand, is the phenomenon of collective misremembering where hundreds, thousands, or even millions of people can incorrectly remember together. It is as if during the process of recollection from the prefrontal cortex (the long term memory storage site in the brain) the memory trace slips off the rails. Because of this, people end up making the same mistakes in recollection over and over again, kind of like that dangerously sharp turn on a mountain road—people end up in the same ditch.

Interestingly, though, the namesake of the exhibition—memory palace—is a mnemonic device that is a highly effective method of accurately remembering high volumes of information or data. The idea being that if you organize information as if it were objects in a room or house, you can mentally walk through that space and recall the information spatially. Imagine trying to remember every country in the world: Canada is next to the shoe rack by the front door, France is on the mantle of the fireplace in the living room, Mexico in the kitchen knife drawer, and so on and so on. Thinking back to that moment of walking through the door at Franz Kaka, it almost seemed like I was walking into a memory palace made physical. Each work in the exhibition appeared to me transcendent, or not of this world, as if some things cannot be translated from psycho space to physical space.

The perils of translating memory from one realm to another reminds me of Simon Critchley’s book Memory Theater (2014). Critchley’s auto-fictive main character is forced to reckon with his own mortality when a close friend passes away and leaves him a memory map. The map uses every detail of the fictional Critchley’s life to date to extrapolate the rest of his life— including the exact day and time of his eventual death. As Critichley’s predicted death day approaches, he decides to make real his most idealized memory theater including every object he thought told his life’s story. But when the exact day and time finally arrived, a death did not. After this anticlimax, it is clear that the virtue of the memory theater is that it is self-generating and self-altering when it exists within the imagination. Critchley’s memory theatre, an assemblage of objects, rendered it as a theatre of death locked in place to the rules and laws of the physical world. However, Cameron’s Memory Palace achieves a psycho-spatial gestalt through the power of the work of art that both exists physically and pliable (or round) so as to remain what Critchley calls—a rotating eternity.

When I look again at Cameron’s prints, I see her intuitively navigating the threshold between built space and the space of memory. The prints appear like vignettes of memories, happenings, and maybe even fantasies. They are intuitive and quickly executed almost like a flickering film strip that has no beginning or end. Cameron’s prints appear as an impression of this world, not a document. The washes of colour feel like a lucid dream or foggy memory where the amorphous shape becomes a vague sense of a thing, after all the details fade away. Cameron appears to have taken caution where Critchley’s character did not. Critchley made the mistake of following the clues of his map to a literal conclusion, whereas Cameron seems content to keep the exhibited prints in a state of flux where subject matter leads to analogy and analogy leads to memory. Here the process of the image trace is on display, not the memory itself.

Friday, October 2, 2020:

Parker,

It’s strange to me that there should be a highly effective method of remembering things spatially, because spaces are already so crowded with memories. Won’t they all get mixed up together? I worry that France will nudge up too close to all my preconceptions of mantles and fireplaces and I won’t be able to tell them apart. How do I find a room free from any past in which to place things?

Yesterday while running an errand, I found myself accidentally retracing the route from my house to the gallery, and I remembered that when I eventually went some days after you, I got lost, thrown off by a keypad at the door for which I had no code. I circled around the building again and again, becoming more self conscious and more convinced that someone was watching me from the top floor window, shaking their head. The door, it turned out, was open.

You didn’t answer my question about dinner.

Thursday, October 8, 2020:

Madeleine,

Two words: pesto, pasta.

Getting lost on the way to a place is almost better than the eventual arrival. When lost, every step becomes charged with potentiality. Sometimes I set out on my bike, very much as you saw me that day on Symington, with the intention of going nowhere. By methodically going nowhere, every turn is steeped in the drama of disorientation.

I’m just revisiting the press release and G. William Webb writes that Cameron’s exhibition is “buried with notations, remarks and treasures ready to be excavated.” We’ve talked a lot about maps, ruins, pathways, theatres, and palaces, but through our correspondence I’m struck by the importance of our own subjectivity through memory and imagination. In other words, yes, we are excavating buried treasure while also simultaneously creating the jewels in the treasure chest. I used to be scared that all the things I believed in most were actually things I created, but I’ve recently come to accept that meaning comes from the interplay between discovery and creation. What I’m trying to say is the room you are looking for, free from any past, is right there. You just created it by saying it. How fun!

Saturday, October 10, 2020:

“Memory Palace” closes.

- Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 82.

Memory Palace by Robin Cameron ran from September 10 – October 10, 2020 at Franz Kaka in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: Installation view of Memory Palace by Robin Cameron. Photo courtesy of Franz Kaka.