Fermentation for the Spirit: Auto-reflections on the rise of sourdough art and glutinous practices. Part 2

9 July 2021

By Lauren Fournier and Greta Hamilton

This essay is the second in a three-part series on culinary fermentation practices and their recent associations in the art world. “Fermentation for the Spirit” considers the rise in popularity of sourdough bread baking during the start of the pandemic, while theorizing on the larger social, political, and cultural potentials of fermentation.

GH: The winter I started making sourdough, I also kept a fermentation diary as documentation for a conceptual art class I took with Amish Morrell at OCAD University. The diary was intended to function as a how-to for sourdough bread, inspired by instructional works from conceptual artists like Yoko Ono, Lee Lozano, and John Cage. It chronicles the origins of my sourdough starter, its multiple deaths, the many flat loaves of bread I ate with various soups, my relative hunger and fullness, the smells and tastes of my domestic surroundings. It was an attempt to present the document of a material process as a final artistic product—a tactic used by conceptual artists when materials were scarce and materiality was deemed overwrought and commodified. While writing the diaries, I meditated on the possibility of decentering materiality in a contemporary sense, perhaps held in the potential of writing.

Excerpt from the Sourdough Diary, 9 November 2018:

We’re all bound to our bodies and the durational performance of life in them. Our bodily labour, the remnants of life, our relation to and intimacy with materials, when documented, elevate life and the mundane to art; labour, time, decay, to art. I wonder, cynically, if the legacy of conceptualism has allowed us to return to pure materiality without a conceptual sensibility, namely in the trend of every-medium-as-sculpture with no countercultural subtext. But I know, too, that there is a present sense of making with urgency, making for survival, making with waste and destruction. Our material practices should be imbued with intimacy and relationality, with the possibility of collective survival. It’s selfish to eat the bread alone. It’s wasteful to throw out the butt end. To honour the life of natural yeast and its ability to grow, overnight, in water, to feed it more than just yourself.

?

LF: I say that I am a baker because I bake; it is something I have developed into a skill by practicing over and over. It is also a kind of identity. The root of my surname, Fournier, is the French four, for oven. “Fournier,” then, translates roughly as “one who uses an oven,” or “one who bakes.” I know little about my paternal ancestral background, and getting in touch with fermentation traditions in the various countries of my familial origins has been a way to become more acquainted with my cultural identity as a white settler raised in Treaty 4 territories, Saskatchewan, on the colonized lands of so-called Canada. I find some footing in the etymology of my name, these working-class roots as bakers still holding true to my working-class family. There is a similar grounding feeling when I bake sourdough bread, as if by mixing watery dough and microbes in my hands, back home with my parents in Regina, I am rooted in the present. In the mornings I go for walks along the creek that connects through to Wascana Creek, from the Cree Oskana, the same creek I’ve walked since childhood. Watching the ducks move in and out of the water as the light of late spring sun illuminates their royal blue necks, I ask myself: Where do the ducks go when the creek freezes over? The yawning sky makes me dizzy, where geese are flying back in for the summer.

At home my starter starts bubbling, meaning it is ready to be mixed with more flour, water, and salt to become bread. I hold the starter jar up to my nose and inhale deeply, taking in its salty, oceanic scent—it smells like the origin of the world. My sourdough starter was the body I was most intimate with during the pandemic, when I was single and largely isolated. I felt a kind of contentment with these microbes, my “primary relationship” being with the billions of bacteria living on, around, and within me. All I needed was bread, butter, eggs, and greens on toast, then writing and reading—energy in, energy out—and I felt nourished. A year out from the end of a long-term relationship and not yet ready to be enmeshed with another human in that daily, lived sense, I was more interested in enmeshment with microbial bodies, extra-human entities like the accumulating stack of kombucha SCOBYs that I fed every 14 days with a room-temperature mix of black tea and sugar.

?

GH: Continuing my sourdough diary, it grew to be less a how-to guide for sourdough bread, and more a document of my daily consumption. I wrote about books I read, art I saw, sexual encounters, love, and friendship. It became a diary like the many I have kept my whole life—a record of the rituals spanning my material existence. I recognize the sourdough diary as two things: first, a chronicle of self-care through my tea drinking, soup making, bread baking, and body washing; and second, a catalog of disordered eating that monitored and aestheticized my consumption. By tracking my materiality, the sourdough and its documentation made everything into a ritual and a meditation on my spirit.

Excerpt from the Sourdough Diary, 30 November 2018:

two loaves have passed since the last writing and I want to say that it was spiritual unrest that kept me from it. something requiring bloodletting for the soul, drainage for the spirit. it was a sour week without decompression and many ill feelings brought up from the past. like, I was in love once without remorse, and, God I am vain sometimes. It’s all winding down with baths and walks and weed, runs and braids and clay. The most essential, castor oil, coconut oil, rosemary oil. If the martyr complex has passed through the psyche, it’s certainly finding its way back again through the purging of body, skin, and hair. Letting the air swell up inside…. Yes, I always forget the salt.

?

LF: Fermentation has been hailed for its superfood and probiotic properties, and marketed for profit accordingly. So, too, has it become a long sought after solution to the gut-wreaking havoc of eating disorders. Some artists and writers have told me their eating disorders were cured by drinking kombucha or consuming other probiotic-rich foods.1 I’m wary of these claims, though I understand what they mean as someone who has healed from a life-threatening eating disorder over a decade ago, and have experienced the minute transformations in my gut-brain relationship after incorporating fermentation practices into my life. In Critical Booch, Andrea Creamer and I, in conversation with Tyler Bigchild (of the DTES Drinker’s Lounge) and Jon Ruby (of Carlington Booch), explored fermentation as harm reduction, looking specifically to the context of alcoholics and alcoholics in recovery. Now I read up on emergent science that exists on the “vagus nerve,” the network of nerves that ties the gut to the brain. The emergent empiricism that dismantles Cartesian dualism is thrilling: the body-mind revealed as one quite literally.

I teach a first-year art history survey class as a six-week intensive, which has taken place online for the pandemic summers of 2020 and 2021. The course focuses on key visual concepts from modernism through postmodernism. My task is always to figure out how to teach “the canon” while also deconstructing that canon; what should be preserved, and what can be transformed? Inevitably, conceptual art crops up throughout the term, beginning in the early twentieth century with Dada artists like the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Duchamp, then in the mid-century with Fluxus artists like Yoko Ono and Shigeko Kubota, eventually becoming defined as capital-C Conceptualism in the 1960s with the work of Adrian Piper, Lee Lozano, and Sol LeWitt.

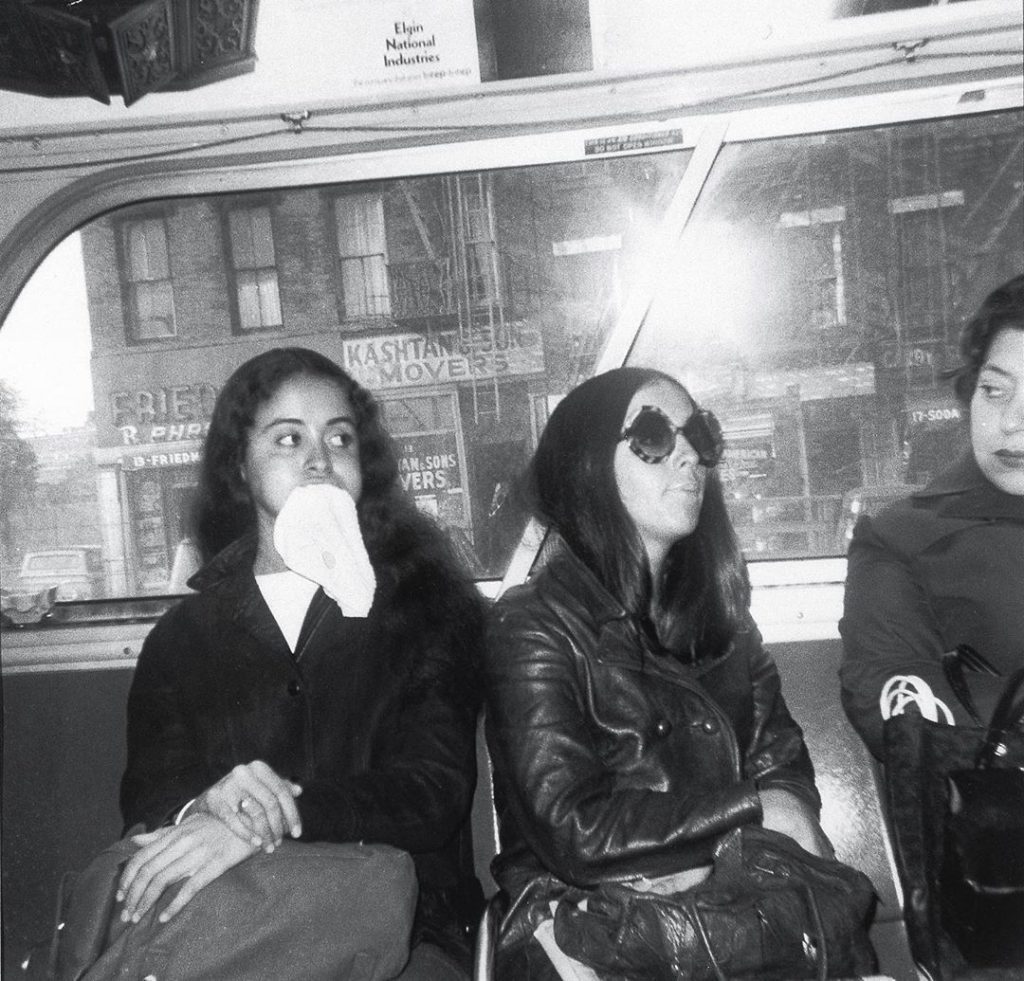

Piper’s conceptual art and philosophy practice might be described as “sour” in the best possible way. In Catalysis (1970-71), Piper’s ongoing series performed in various public sites around New York City, the artist boarded the subway during peak traffic hours wearing clothes that had been soaking in eggs, milk, and fish oil for a week, causing it to smell of rank food decay. In another work in the series, Piper wears a sign that reads “Wet Paint” as she walks the streets of Manhattan and through an upscale department store, a hypothetically haptic testing of boundaries between her body and the bodies of others. The series tested the limits between her and those with whom she came into contact in her daily life, through both visual signifiers and scents.

Food tends to appear only peripherally in Piper’s work, such as soaking her clothes in it, but also in the negation of food. Her work that centres on fasting sometimes makes me uncomfortable, admittedly, bringing me back to memories of my own eating disordered states. Fasting appears most famously in her durational performance art work, Food for the Spirit (1971), where the artist fasts in her Manhattan studio while reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. It also appears in references to her teenage diaries—mined as part of her ongoing performance, The Mythic Being (1973)— in which the then-teenager describes her mom buying “cakes and cookies,” despite Piper’s begging her to stop, as these sugar and flour-laden treats were temptations she wanted to avoid at all costs. She also took these diary texts and re-contextualized them in her image-text pairings for the Village Voice in the 1970s. I read the work as orthorexic, even anorexic, though my contextual information is limited and I am left as an art critic to the realm of subjective speculation. The 2017 memoir Swallow the Fish, by Black performance artist and writer Gabrielle Civil, is the first time I encounter the idea of thin privilege in writings on contemporary art, commenting on Piper’s thinness as an aspect of what her work performs politically, alongside her light skin.

?

GH: We studied the work of Adrian Piper in class, and her photographs and performances resonated with me while writing the sourdough diaries. In The Mythic Being, Piper dresses in drag, becoming an androgynous character who recites lines from her childhood diary as she walks the streets of New York City. She repeats in meditation: “No matter how much I ask my mother to stop buying crackers, cookies, and things, she does anyway and says they’re for her, even if I always eat them. So I’ve decided to fast.” Rather than satisfy her physical needs, Piper’s determination in this work is to go hungry. How does this mythic being sustain themselves, if not through food? Perhaps through language alone in the recitation of a mantra. The idea of language as sustenance is echoed in Food for the Spirit, in which Piper documents herself fasting for the duration of a summer. Exchanging food for philosophy, she reads Immanuel Kant and records her disappearing body with blurry black and white photographs in the mirror. Her body recedes further into her domestic space, sustained only by Kant’s writings on metaphysics. What is it about the erasure of the body for the attainment of creative and spiritual fulfillment that propels Piper’s work? Perhaps it is to be sustained on language alone; to write, to read, to be thin, to see oneself as an artist, or as a starving artist. The work seems to affirm the possibility of being fulfilled by negating the body. If language can sustain a body in place of food, if creative and spiritual fulfilment arises through the denial of bodily needs in exchange for language, where does that leave food critics, fat writers, and writers who love to eat?

In 2019 I saw a number of talks and exhibitions by artist Moyra Davey, including a retrospective of her work installed at the Ryerson Image Centre for the Scotiabank Photography Award. Davey held artist talks and screenings while in Toronto for that cold spring. She spoke of her video Wedding Loop (2017), which included references to Virgina Woolf and Julia Margaret Cameron, as well as her video Hemlock Forest (2016), in which she reckons with the death of French filmmaker Chantal Ackerman. What struck me most in Davey’s work was the recurring references to hunger and language. Throughout Wedding Loop, Hemlock Forest, and in a coinciding text, “Walking With Nandita” (2017), Davey describes a tenuous correlation between eating and writing wherein one propels, or otherwise inhibits, the other. She points to a paradigm in which language evacuates hunger. She juxtaposes Ackerman’s binging powdered sugar in Je Tu Il Elle (1974), in order “to fuel the manic, around-the-clock-writing,” with Woolf’s alternating periods of starvation and gorging, during which she stuffed herself with beef, milk, and malt extract, and did not read or write.2 Within this paradigm hunger is satisfied by writing. As such, an evacuation of language is an evacuation of bodily necessity, and these masochistic eating habits fuel the creative process.

This same pattern in Davey’s work made me think of my body and the self-abuse it has sustained in order to maintain my self-image—starving not because I am an artist, but because of my eating disorder. I think of my susceptibility to purging for perceived spiritual and creative benefits, and the error in my mind that tells me to go hungry rather than satiate my needs. Why is it there a cultural sensibility of creative fulfillment that relies on purging? Why is the narrative of women writers so often that of negation, giving up love, food, sex, and public life in order to write? Otherwise it is the stark opposition of hedonism. Has the body not given up enough?

?

- Jessica Bebenek makes this case in “Something That’s Dead,” their contribution to the first iteration of Fermenting Feminism (Berlin & Copenhagen: Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, 2017).

- https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/892_walking_with_nandita

Feature image: Catalysis IV, 1971 by Adrian Piper. Courtesy of Generali Foundation.