Fermentation for the Spirit: Auto-reflections on the rise of sourdough art & other glutinous practices. Part 1

30 June 2021

By Lauren Fournier and Greta Hamilton

This essay is the first in a three-part series on culinary fermentation practices and their recent associations in the art world. “Fermentation for the Spirit” considers the rise in popularity of sourdough bread baking during the start of the pandemic, while theorizing on the larger social, political, and cultural potentials of fermentation.

As more artists make work that exists between art and food, is there space for art writers to also be food writers? In the early days of the pandemic, we were struck by the importance of food and fermentation to us as writers and artists, but first and foremost, as humans who were hungry. We found ourselves asking: Do I care about food and fermented materials more than I care about art or the work of criticism (and by extension, language, research, and articulation)? Do these have to be kept separate? Why not mix them together and let them autolyze? What would it mean to expand the task of the art writer or critic to include the work of baking, gardening, activism, community organizing, planting native species and pollinator gardens, preserving and sharing those seeds, composting, telling stories, building libraries, building homes, tending to microbiomes—both within and around us? Can the work of art writing and criticism include all the work that nourishes a community, that feeds us physically, affectively, and spiritually, as writers and as people with guts?

We spent this past year reflecting on the relationship between art, writing, and bread; as we did so, fermentation served as an entry point for our explorations. The process of fermentation, that is, of microbial transformation, changes a substance through a Symbiotic Community of Bacteria and Yeast (SCOBY). We ask, then, what can the practice of fermentation for bread, kombucha, pickled vegetables, and preserves offer us materially, theoretically, socially, and politically? We suggest it offers a framework for thinking through multispecies relations, reframing anthropocentric reproduction and storytelling, as a potential mode to fabulate communities in the ruins of late-stage capitalism and climate crisis. Thinking with fermentation requires thinking with the durational processes of decay and rot, time and rest. It means thinking with cultural foodways that have been violently altered by colonization and extractive capitalism, as well as neoliberal discourses of sustainability and care, and the concomitant cultural normalization of eating disorders, orthorexia, and greenwashed dieting. Thinking with fermentation requires a curiosity about the subversive possibilities of food and fermentation practices, including wheat/gluten fermentation in sourdough bread.

?

Lauren Fournier: “LIFE IS TOO SHORT FOR COMMERCIAL YEAST,” reads the Instagram profile of one of the many sourdough bread bakers in my feed. I began following a handful of bakers in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, finding their livestream stories and posts about bread baking and fermentation to be just the nourishment I needed at the time. Sourdough seemed to fill a void and offer something to people. It was a way to sustain yourself and those in your household with only flour, water, and a bit of salt. When a toilet paper shortage also became a flour shortage, people who may not have baked in years were buying giant sacks of flour and becoming veritable bakers of bread.

In those early pandemic days, I tuned in to two free, weekend-long fermentation festivals.1 Accessible through Instagram Live, the festivals brought me into the domestic kitchens and other environments of fermenters around the world, teaching hands-on skills like beginning a sourdough starter, baking sourdough bread, and preventing food waste by making kraut with whatever veggies you have on hand. Scribbling down recipes and ingredients to buy during bi-monthly grocery runs, I left a note to myself in the margins: can I get into food writing? It wasn’t clear from whom I was asking permission—the editorial gatekeepers of food writing and kitchens? Around this same time, there were localized revolutions and revolts happening within established food journals, with Bon Appétit being called out for its structurally racist actions toward racialized staff: It was revealed that BIPOC employees were consistently paid less and had more precarious jobs, among other inequities, which included being marginalized, quite literally, in terms of how they were represented in the journal’s famed food preparation videos.

These fermentation festivals were a real highlight while sheltering in place. I was living alone and technically out of a suitcase, without a home or place to call my own since late fall 2019 (this, due to a range of intersecting reasons, including a separation, a concomitant temporary move, finishing my PhD, and having to cancel travel plans for research). The festivals featured a diverse range of fermenters sharing their traditions, tools, tips, and crafts with audiences across national and geographical borders. There was a pang of guilt when I realized that I found these festivals much more engaging and desirable to attend than the virtual art and academic events of 2020. This conflicted feeling contributed to my existential crisis about not being a “good art person” or a committed enough academic—about preferring, in a time of physical distancing, social isolation, and quarantine, the world of food production and fermentation (another form of “cultural production”) over the world of contemporary art and discourse. I wanted to make something in my kitchen while tuning in virtually, and then be able to eat or drink it while listening and engaging through the chat on issues related to food, tradition, and sharing. So I continued to gravitate toward food events instead, which felt more generative than just sitting in front of a laptop screen, trying my best to ignore how much my back hurts while “listening.”

?

Greta Hamilton: I left Toronto for the West Coast a couple of months into the pandemic. I felt a pull to return to my family’s home, a longing for the comfort and familiarity of the place I grew up. I had ached to go home before, having always been a little disoriented in Toronto without the view of evergreens, or the guiding sound of the tide against the rocks. A handful of summers ago my dad mailed me a care package from his garden, including black currant jam, hot chilies with starter seeds, and a bundle of lavender to tuck into my pillow case. The scents of his garden wafted into my muggy Toronto kitchen. I started baking sourdough bread as an experiment for a conceptual art class a couple years ago, and my dad has maintained a practice of baking sourdough on and off throughout his life. When I returned to live with my family in May of 2020, we began baking it together. As a former hippie and back-to-the-lander, my dad values practicality. He raised me with a do-it-yourself attitude towards food: If it could be made at home, it would be, in the fastest, cheapest way possible. He made a sourdough starter in the early months of the pandemic, and we tried out recipes for overnight no-knead sourdough bread. Our best variations were rye with molasses and caraway, multigrain with fennel seeds, and my favourite, multigrain olive bread.

After a year in my family’s home, I’ve left again with my dad’s starter in hand. Baking bread with him, I felt connected to his homesteading, back-to-the-land past. In the early 1970s, when he was just older than I am now, he and his wife immigrated to Northern British Columbia to start a commune with a wave of hippies, anti-war protestors, and artists. He told me about the crock we kept our sourdough starter in, how his wife had kept it between her feet in the pick-up truck on the drive from Texas to Canada. She had used the cotton bags from their flour to sew the pastry cloth on which we now folded our dough. The dough rose overnight in a large ceramic bowl, one whose origins I mythologized over the years and mixed up with one of his stories about the Marshall pottery workshop in Texas, where vessels are denoted with two thin blue lines.

It strikes me that, in my dad’s stories, so much of the domestic labour was completed by his wife. Though he often reassures me that the labour distribution was fair (queue his story about single-handedly building a road that caused the demise of his marriage), it seems to me that the domestic labour, despite being at the core of homesteading, was still undervalued within a countercultural movement. This gendering of labour points to one of the failures of communal living in the 1970s. Perpetuating gender roles within the purported non-hierarchy of communal living arrangements conflicted with the budding feminist movement across urban centres. How was the feminist movement of the 1970s supposed to look outside of the city, where labour was enmeshed with the domestic realm—living off the land, building a home, growing sustenance? When considering the implications of the back-to-the-land movement, in addition to the gendering of labour and despite any anti-capitalist intentions, it is difficult to deny the neo-colonial aspects of settling a rural place to develop some new or bohemian way of living. As much as this movement was about self-sovereignty and a communal ethos, it also reaffirmed the notion of private property—that land should be bought and owned by settlers, and farmed for their sustenance.

As we grew closer through our shared practice of baking bread, I asked my dad about his back-to-the-land days. I asked him if he thought about his wife’s labour as lesser than his. I asked, too, about the colonial implications of settling the land he built his home on, about the community he was a part of, and what his political affiliations were at the time. We spoke about feminism and civil rights in the 1960s and ’70s, as well as the later disintegration of countercultural movements in the face of 1980s neoliberalism. He didn’t answer my questions directly. As it turns out, it’s challenging to get an honest and straightforward answer when interviewing a family member, or even an answer that provides an adequate sense of scope. While I didn’t find what I was looking for in our conversation, I still wondered about the demise of communes. How might the sensibilities of a countercultural movement be retained to inform how we organize our social structures and cultural movements now? How do the failures of that movement impact future ideas of labour within DIY and communal practices?

Folding the dough into loaves with my dad, I thought about our shared position as settlers, and what I inherited from him. I thought about how his life reflects a particular history of activism that ultimately perpetuated traditional gender roles and settler colonialism despite its veil of radicality. Thinking about the community of bacteria and yeast we grew together: Can fermentation be one mode of understanding my relationship to the land I occupy more deeply, by attuning me to the microbes, cycles, systems, and histories that sustain me?

??

LF: “Were you making sourdough before the pandemic, or did you just get started?”

This is a question I was asked a lot over the course of 2020, to which I’d smile and respond, “Before.” I started baking sourdough in 2015, getting my sourdough starter from a workshop at the West End Food Co-op in Toronto. The starter has now been alive for 6 years, travelling with me and changing its constitution to Regina, Vancouver, and San Francisco. While it is true that I have been a sourdough baker for a while, answering “before” felt as if I was claiming some kind of cred as a “true” baker, not someone who hopped on the sourdough bandwagon. In those moments I felt like the fixed-gear-riding-stretched-earlobe dude played by Fred Armisen in Portlandia, who rides around town trolling people with his overwrought critiques: “That bar is over,” “Shell art is over.” Trend-chaser logic asserts that once a practice or place is no longer on the margins, it loses its cachet and should be avoided. But this logic risks cancelling practices that have real political, social, even ethical potential. I want to resist sourdough’s co-optation into a trend, because once it is seen as “trendy,” it is vacated of its substantive content or context. Trendiness puts an expiry date on the lifespan, appropriating something with millennia-long, cross-cultural histories, making it into a meme.

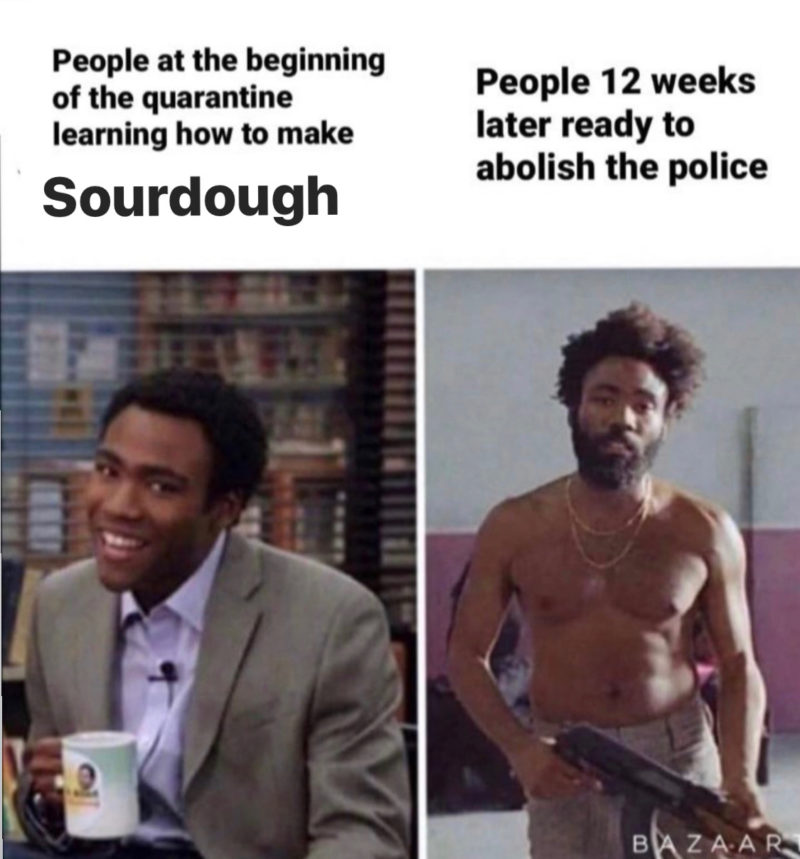

The meme-ification of sourdough over past year was entertaining. It is true that sourdough had become mainstream, so popular that it was now being parodied and problematized. Sourdough was once on the margins, being made only by those who could be at home for a long enough period to follow the process from start to finish. On average, it takes about 16-20 hours to make a single sourdough boule (the name for a round loaf of bread in the French baking tradition). This time period includes feeding the starter all the way through to baking the bread at 450 degrees Fahrenheit; typically, 8-12 of those hours can occur while asleep (I suggest feeding your sourdough starter before going to bed, and starting the bread-making process in the morning. One could also take naps or otherwise find affirming forms of rest while the dough is rising). The pandemic swiftly changed the temporal marginalization of sourdough baking: Now most everyone, save for frontline and other essential workers, as well as the under-housed and houseless, was at home. The conditions were set for the rise of sourdough baking among the masses. More people found themselves standing at their counter, stirring water and flour in a mason jar or crock, watching as bubbles emerge from the cereal swamp of microbes that live at the bottom of the mixture.

In resisting the “trendiness” of sourdough, I also resist the tendency to view sourdough and other fermented foods like sauerkraut and kimchi as artisanal, handmade goods for the bourgeois. Understanding these foods as cultural products grossly obscures the diverse historical contexts from which they come. Consider that many Eastern European families, those like my ancestors in Romania, Hungary, Ukraine and former Bohemia/Czechoslovakia, would keep sauerkraut fermenting in a crock in their kitchens. Chinese and Russian families, for example, would have kombucha, the effervescent tonic from tea, fermenting in a crock in their home. Korean families would ferment kimchi; Ethiopian families would make the fermented flatbread called teff; and Iranian families would make the fermented flatbreads sangak and barberi. I could go on. I want to resist the class and race divides that are perpetuated when fermented foods are commodified and upsold, making them costly and only accessible to those in the middle and upper classes. More people need access to the means of production of their food, and fermentation offers a way to achieve this.

To be sure, the narrative that “fermented foods are for the bourgeois” perpetuates ever worsening class divides. When this narrative takes control, the wealthy continue to have access to presumably more life-affirming foods, and more empowerment in their processes of production, to the ongoing detriment of those with less material power—including, more often than not, those who are racialized.2 Those with the financial and educational know-how can paradoxically make use of the cheaper, more accessible back-to-the-land processes of making and preserving foods—like the spontaneous fermentation that gives rise to naturally-occurring yeasts for sourdough bread. Right now, it feels all the more urgent to challenge narratives that deepen the staggering gap between classes, and the ideological divides that fuel social division and disenfranchisement. Making fermentation more accessible, including having more people bake sourdough bread, might seem silly, and yet I see it as a radical way of transferring the means of production to the disenfranchised.

As a baker, I am invested in and inspired by the possibilities of using ancient technologies like wild yeasts in sourdough bread baking to remedy structural issues like racism (including but not limited to anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, Islamophobia, and environmental racism). One direct example would be the phenomenon of food deserts in underserved communities. Last year a “free food forest” was officially opened in Atlanta, Georgia, located in an area largely populated by Black Americans that was previously a food desert lacking access specifically to fresh produce. Now the land is open for communal foraging. This kind of news about pathways to better food futures is what I find exciting.

I will be exploring the possibilities of sourdough bread baking and anti-racist world-building in the fall with Ashley Jane Lewis in a collaboration for Durham Art Gallery. Lewis has been leading “Fermentation as Revolution” workshops this past year, first through Vector Festival in Toronto (2020) and most recently at Genspace, the first community bio-art lab in New York City (2021). In it, she leads participants in feeding their starters while reading texts and engaging in conversations about mobilizing and activating fermentation toward revolutionary ends. In a review of the workshop, Lune Ames describes Lewis as teaching participants “how to ferment a sourdough starter while cognitively fermenting on the swift, strategic, and seldom known history of food as a conduit to revolution.”3 Lewis is a new media artist and a trained chef who recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship in machine learning at NYU. She has worked with Black communities in the GTA on coding and other projects that engage technology, literacy, and access. For our collaboration this fall, we will be artists in residence for Teacher, Trickster, Chaos, Clay, organized by Jaclyn Quaresma and guided by the prescient writings of Black sci-fi writer Octavia E. Butler. The plan is to turn the gallery into a functioning bakery for 24-48 hours. We are exploring with open minds the decolonial possibilities of fostering a community sourdough starter in a settler colonial context, creating a sourdough recipe book and manifesto after Butler. In transmuting sourdough through the frame of Butler’s Parable series, we radically reconsider what sourdough starters can do, using the sourdough starter a seed of sorts.

?

- Shoutout to the Florida Fermentation Fest for sponsoring and hosting these: https://www.flfermentfest.com/

- Just as the insidiousness of convenience is a problem—Wonder Bread targeted higher-income white people as a symbol of “clean food,” modernity, and progress in the 1920s, and then later targeted certain lower-income, racialized (most often Black) Americans following the backlash of healthism (“empty calories”), because they knew this was all some could afford, due to structural racism and ensuing impoverishment—then so, too, is the perceived privilege of slow food. It’s all about historical context.

- https://degreecritical.com/2020/09/18/everything-is-contaminated-pt-2

Feature Image: Nothing More to Eat, 2019 by Andrea Creamer. Installation view of Fermenting Feminism at Access Gallery, 2019. Photo courtesy of Access Gallery and Rachel Topham Photography