Nadia Belerique at Daniel Faria Gallery

30 December 2020By Erin Orsztynova

Recently I had a memory come back to me—the type of memory that comes to the surface seemingly out of nowhere, one I imagine would be considered so very mundane that any brain, in an attempt to conserve space, would erase immediately. But there it was, collapsing time, a visceral scene from childhood of me squeezing into the small space beneath my bed. I remembered the tightness of the space, so tight my child-sized head could only fit in sideways. I remembered the smell of the dusty cambric from the boxspring, and the feel of the carpet on my cheek. Close and containing, this small space gave me the experience of disappearing entirely from view, complete with the contradictory desires to both remain hidden and be found.

When navigating the floor of Nadia Belerique’s solo exhibition There’s a Hole in the Bucket, I’m hit with a similar experience of recalling long lost memories from childhood, and just as holistically, I’m instantly disarmed. Visual, physiological, and emotional details float up to the surface of my mind like gnocchi in a pot of boiling water: how could I have forgotten? How easy it is to forget. My memory, momentarily, fills in. Like this snapshot of my childhood, I see snapshots of another’s life. Spaced out in the front room of the gallery is a crop of steel doors that stand upright, independent but in relation to each other, like bodies in a line. Some have windows partially obscured by objects that speak to personal stories known only to Belerique, and to the mundane, beautiful everyday of family and domestic life: photographs stuck in corners, a towel that looks like it was used to clean off the dog, and a baseball cap and leash ready for the next outing. These snapshots are like proof of a lived and shared life—and there must be a dog in there, somewhere?—exhibiting parts of a story, but clearly not the whole story.

All the doors are tarnished in some fashion. Some have holes roughly drilled through the metal, rendering the doors almost porous. Other doors are adorned with stained glass and candles that burn, attesting to some fragility and the passage of time. One door, the show’s namesake, has a stained glass depiction of a hand where a window might have been: a handprint, a moment stamped in time, or perhaps a message from another dimension. Most doors are missing their handles, hinting that we may peer at or through the windows and holes to the other side, but we cannot enter. We are forever stuck on this side of the world.

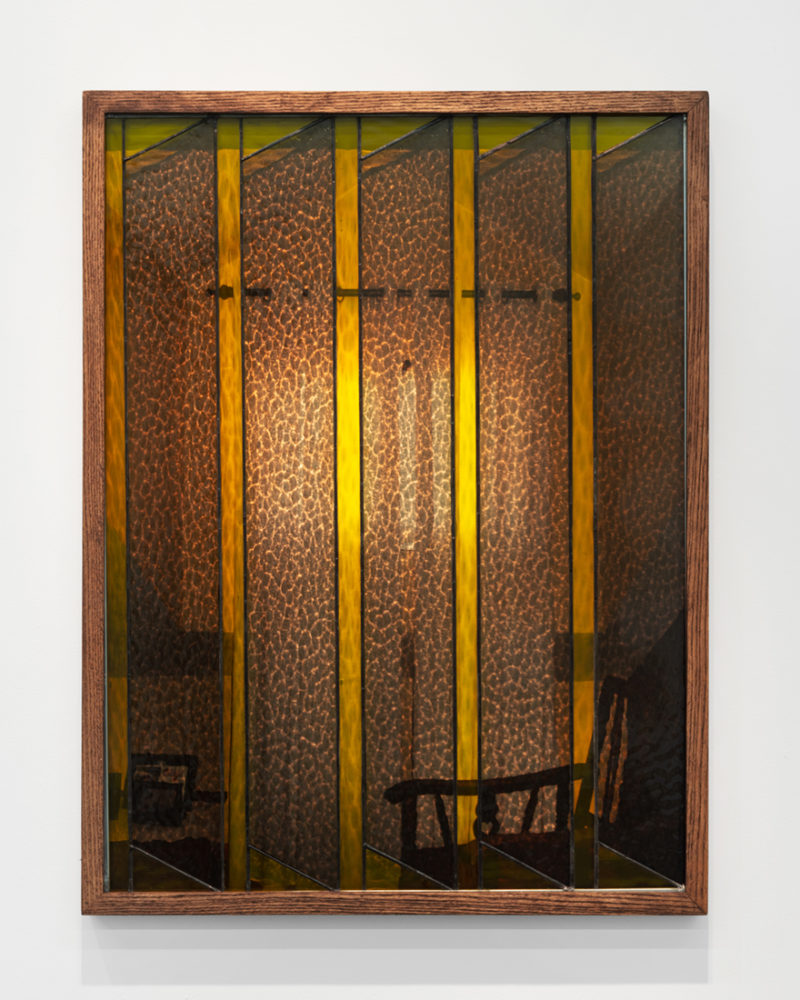

This experience of peering at or in, and the guesswork that sometimes happens when we really want to know or understand something that is being somewhat hidden from us, is carried over for me to the back of the gallery. Here the wall is lined with a series of photographs overlaid by stained glass. The images behind the stained glass are partial and incomplete, and often obscured. We are given bits of information, but must guess at what we’re seeing, or fill in the rest with our own associations. One such image, in My Middle Name (2019), is (what looks like) the corner of an old rocking chair; this image is then overlaid with stained glass that gives the impression of vertical blinds. I feel like an outsider peering into a window at night, catching a glimpse of someone else’s living room. It’s strangely intimate, and I’m not sure I’m supposed to be seeing what I’m seeing. Same with the work Blinds (2019), except in this case the photograph of what seems to be old keys is even more obscured by slat blinds made of a solid white glass.

Keys—things that unlock and open, or keep closed or secret—are not a new subject for Belerique, and were featured prominently in her show The Weather Channel at Oakville Galleries in 2018, as were doors and glass, and the act of obscuring objects from view. As writer and critic Sky Goodden put it, in her review of The Weather Channel for Momus, “These are images of an intimacy at once protected and falling open.” The same could be said here: what strikes me most about these images is how much we are let in, and simultaneously kept out—like secrets both given and withheld. It creates the possibility of a deep ambivalence and relational frustration that might translate to many a childhood or domestic sphere—how much do we really know of each other?—if not also to one’s own personal experience of hidden memory and muted self-understanding.

I suppose, if the faulty container of memory and our understanding of ourselves and others can never really stay full—if there’s always a hole somewhere, or some sort of obscurity—what are we really left with? There’s a Hole in the Bucket reminds me that we can be reminded. We have the outlines of a life, key hints of where we’ve been, who has been there, where we are. We can hold on to the pieces, and fill in the rest.

There’s a Hole in the Bucket ran from September 20 – November 2, 2019 at Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: Installation view of There’s a Hole in the Bucket by Nadia Belerique. Photo courtesy of Daniel Faria Gallery.