Tasman Richardson’s Kali Yuga

7 January 2021

By Madeline Bogoch

In her 1976 essay “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” Rosalind Krauss attempts to pinpoint the singular essence of video-based artwork, speculating on the possibility of the claim that the “medium of video is narcissism”. (1) For Krauss, the linchpin of this perspective was the (now taken for granted) instantaneity of video, which produces perpetual feedback that captures the subject in a closed circuit of “self-encapsulation”. (2) There is an implied intimacy in this simultaneity—while Krauss perhaps over-essentialized the quality of video, she shrewdly identified the implicit correlation between video and the psyche.

In his recent show at Arsenal Contemporary Art Montreal, artist Tasman Richardson mines the intimate condition of video feedback and capture to explore contemporary practices of vanity and voyeurism. The exhibition’s title, Kali Yuga, is a Sanskrit term which translates to the age of vice. In Hinduism, the Yugas are a four-stage cycle of eras, and Kali is the final and terminal phase. This era of degeneration comes to its end in a cataclysmic cleansing in which the world is destroyed, only to be remade in a new golden age. The allusion to end-times positions Richardson’s work as an eschatological narrative, wherein vice, vanity, and narcissism play the role of the apocalyptic horsemen.

Amidst this air of doom, Richardson cultivates a subtext of desire that is sustained in the form of self-obsession and scopophilia. The compulsion to see-and-be-seen acts as an erotic ambiance that drifts between the works. In the installation Going Gray (2019), Krauss’s diagnosis of narcissism in video work finds its proof. The viewer encounters a dark screen embedded in a round frame that projects back to them a weathered image of themselves. The initial captured image bounces between a series of monitors mounted throughout the space, and as the image travels it accumulates visual noise, appearing distorted and aged. The installation is named for the titular character in Oscar Wilde’s classic allegory of narcissism, The Picture of Dorian Gray. Appealing to the viewer’s vanity through the seduction of their own representation is a well-worn gimmick in interactive installation works, but Richardson fractures the seamlessness of this allure with the gathered analogue decay, so that the image gains independence from its source and takes on a life of its own. The life of the image, in this case is grislier than the subject it reflects. In its accumulated grittiness, the installation projects the ugliness of selfie culture, a machine that runs on vanity to fuel the engines of platform capitalism and the looming approach of a surveillance state.

The reflective surface of video was seen by Krauss as exemplary of its “psychological situation,” where the submergence of the subject within the medium prevents the work from achieving true reflexivity. Krauss instead analogized video to a mirror reflection, caught in a perpetual cycle of codependency between subject and object. This perpetuity is claimed as an advantage in Kali Yuga, wherein the climate of closed circuitry enfolds the viewer to simulate the numbing ambience of digital existence.

The father of media art, Nam June Paik, famously stated that “video is time”—referring to the flow of electronic pulses which compose the medium. (3) Richardson’s installation Sands Stand Still (2017-2019) acts like a monument to this declaration. The installation takes on the likeness of an hourglass, in which a pillar divided into two sections is joined by a mirrored cube in the centre, which reflects the noise of an embedded CRT monitor. The cube captures time in the form of electronic oscillations made visible in the mirrored surfaces, which infinitely project the television’s static. The symmetry of the hourglass is reflected in the show’s overall theme of homeostatic equilibrium, with feedback loops serving as the conceptual underpinning of the exhibition.

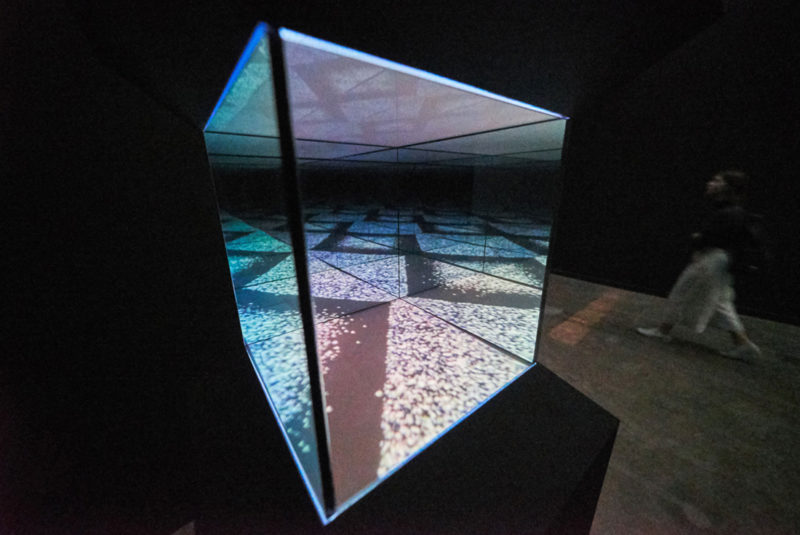

The most visually abstract of the six works is placed at the far end of the exhibition and revisits the perpetuity of closed-circuit feedback. Appropriately titled Ouroboros (2019), after the ancient symbol of a serpent devouring its own tail, the installation is composed of two projectors and two cameras each connected to another’s outputs in order to generate infinite patterns onto the gallery wall. The audiovisual components become a perfectly self-contained organism as the RCA feed is split and redirected into an audio channel, which rhythmically coheres the sound and image into a fully immersive state of hermeticism.

The more violent and insidious nature of contemporary vices are introduced in Sphere of Influence, Circle of Protection (2015-2019). Angled screens forming a semi-circle project dash-cam footage of car crashes, and at the center of the panorama, a circle of mirror shards provide a mystical barrier to the onslaught of chaos and destruction. Each crash is timed in a way so that the footage acquires a rhythm, which, through repetition and saturation, anesthetizes the content. Directly before the moment of impact, a flash goes off, snapping the viewer out of their hypnosis and perhaps communicating that they are also being looked at as they look. The sense of artificial intimacy produced by this enclosure elicits the condition of online viewing, wherein our hyperconnectivity is offset by a commensurate sense of alienation.

Those familiar with Richardson’s JAWA manifesto, may recall a Videodrome quotation placed in the first paragraph. (4) The influence of the 1983 film remains strong in Kali Yuga, with themes such as the desensitization to porn and violence, and an increasing intimacy with screens, which seem to be ripped directly from a Cronenberg-esque universe. Richardson seeks to shatter that desensitization by striking at what Krauss observed decades ago regarding the relationship between the psyche and screen.

Inverting the logic of Going Gray, which collects multiple spaces into a singular moment, The Cave (2019) depicts multiple moments within a single space. (5) The installation offers viewers a partially obscured view of a couple engaged in intimate acts. In the recording the couple are projecting a video of themselves onto the wall behind them, thus creating an exponential cascade of temporalities collapsed into a singular frame, with the light from the distant projections illuminating each ascendant image. Borrowing from Plato’s Cave, Richardson again uses allegory as a device to examine our technologically mediated understanding of time and reality. (6) Here, however, the former narrative is inverted—the source of light is found deep within the cave rather than outside of it. While Plato argued for the triumph of the rational over the sensorial, Richardson appears more interested in rehabilitating the latter.

Though the philosophical allusions are clear, whether or not there is any moral polemic in Kali Yuga is left up for interpretation—it seems that the artist is less interested in drawing firm conclusions than in using the surface of the screen as a reflective mode of cultural inquiry. A similar process is at work in Fire and Theft (2009), a second panorama of screens, which collapses the phenomenon of solar trajectory. The installation’s title refers to the myth of Prometheus, the Titan who steals fire from Zeus as a gift to humanity. Across the multiple vantage points, the viewer is shown live feeds of the sun at various altitudes. Confined to its perpetual circuit throughout the installation, the sun becomes a prisoner of the surveillance state, and the motif of fire in the story of Prometheus becomes a potent metaphor for technology as a tool—which can be instrumentalized for both vice and virtue.

Our increasingly codependent relationship with screen technologies enables us to simultaneously pursue our most pleasurable and destructive desires. The tension between these compulsions is on full display in Kali Yuga, which sets up a series of binaries that are reauthored as part of a full circle of feedback. Hyper connectivity and alienation, narcissism and voyeurism, and destruction and creation; Kali Yuga presents these ideas not in terms of their opposition, but rather their reciprocity with one another. The dystopic energy established by the exhibition is supplemented with the promise of regeneration—a sense of ruin and renewal embedded in the fabric of time. These allusions bring a quality of timelessness to the hyper-contemporary themes of the show; our extremely-online condition appears at once disorienting, dreamlike, and perennial. In 1976 Krauss wanted to identify narcissism as the essential quality of the nascent art form of video. Several decades later, it seems like Richardson is willing to consider it as the preeminent quality of contemporary culture itself.

1. Rosalind Krauss, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” October vol.1 (spring 1976): 50.

2. Ibid., 53.

3. Maurizio Lazzarato, “Video, Flow and Real Time,” in Art & the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, ed. T. Leighton (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), 288.

4. The JAWA Manifesto was authored by Richardson in 1996 and outlines his methodology of video scavenging and collage. http://www.incite-online.net/richardson2.html.

5. Anna Kovler, “Watching Me Watching You Watch Me: In Conversations with Tasman Richardson,” Arsenal Contemporary, last modified November 2019, https://www.arsenalcontemporary.com/press/2019/11/watching-me-watching-you-in-conversation-with-tasman-richardson?tag=mtl.

6. Ibid.

Kali Yuga ran from September 17, 2019 – March 20, 2020 at Arsenal Contemporary Art Montreal in Montreal, QC.

Feature Image: Ouroboros, 2019 by Tasman Richardson. Photo by Romain Guilbault courtesy of Arsenal Contemporary Art Montreal.