Speculative Methodologies: Veils of a Bog at the Western Front

13 December 2018

By Gillian Haigh

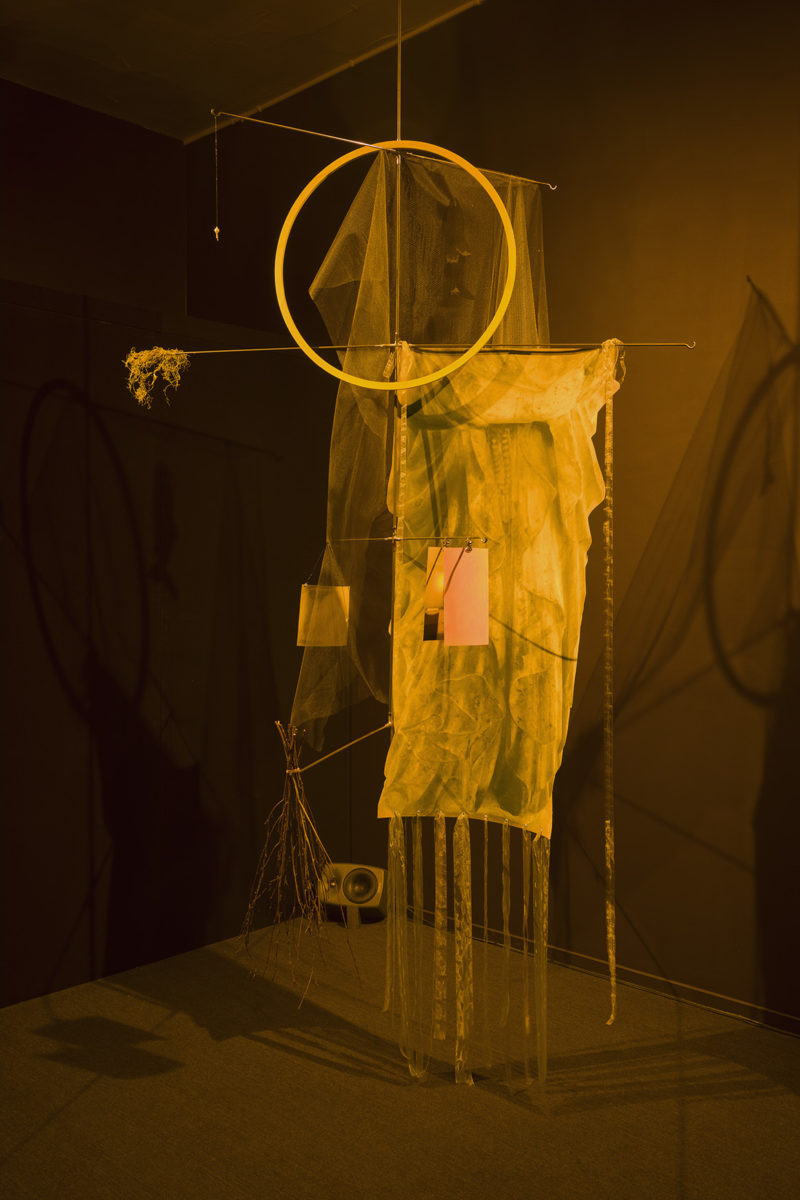

Just beyond the small reception area of the Western Front, a black doorway called to me. Inside, a chorus of echoing crickets and croaks harmonized with an unworldly drone. The noise beckoned me into the tenebrous space, pulling me through the doorway into a cloth hallway cloaked in total darkness. The room opened up to reveal a dimly lit space with three large metal mobiles laden with collections of fabric, moss, dried leaves, flowers, photographs, and other found objects. The materials hung, some sweeping the floor or wall as they slowly rotated on chains. These strangely figurative compositions, coupled with the otherworldly symphonic hum of the soundscape, welcomed visitors to sink into the bog.

Veils of a Bog is a collaborative exhibition between Vanessa Brown’s sculptural practice and Michelle Helene Mackenzie’s Post-Meridiem (2018) soundscape composition. Hosted by the Western Front, an established artist run centre in Vancouver BC, Veils of a Bog is an experimental installation that investigates the liminal landscape of a bog as a place of decay and new life—a space that is both unnerving and calming, repulsive and enticing.

From a distance in the partial darkness the large, slowly revolving mobiles seemed figurative, with ovoid shapes near the top and limbs branching out from the centre. The growing noise of the bog drove me forward, and as I moved closer, the materials revealed themselves: draped gauze and ribbon created curtains that caught the dim yellow light. Watching the mobiles turn, I came across a paperclip and a fishing lure so matted into the mesh, it looked as if it had been dredged up from the bog’s depths. Moss sprung from the metal armature like a vigorous weed and bundles of dried grass were carefully attached to the rotating frame, brushing the walls as it passed. Indistinct photographs—reminiscent of limbs—were suspended and turned slowly between image and blank back-sides. The competing yet harmonizing sounds of bog critters combined with the unnatural droning tones aided in transforming the exhibition into a fully immersive ecological landscape.

Within the exhibition, the relationship between the representational and the real became blurred, therefore not only imitating the elements of a bog, but also redefining them as a metaphorical space of liminality. In the dim light, the forms of the mobiles themselves oscillated between signifying structures in a forest, or figures, be it human or something more ghostly. The darkness heightened Mackenzie’s soundscape, calling upon a summers evening with the familiar sounds of crickets chirping, frogs croaking and the warble of birds calling out in the night. From the organic symphony of the marsh emerged the underlying drone, growing into waves of sound that, at times, drowned out the various chatter of the bog’s creatures. The origin of this unnatural noise is unclear—at first I believed it might be something mechanical—but the drone’s ethereal quality and shifting monotonous complexity suggested otherwise. Together, Brown’s use of industrial and organic materials merged with Mackenzie’s enveloping soundscape to perform the unfixed, unsettling, and often contradictory space of the bog. Even though the exhibition is hardly an accurate representation of a natural bog, it more directly addressed its ‘veils’—its mysterious and mystical nature. The work called for getting lost in this metaphysical space.

Contemplating the work, I recalled Rachel Jones’ essay “On the Value of Not Knowing: Wonder, Beginning Again and Letting Be.” In her essay, Jones took the theme of ‘not knowing’ as a strategy for art making and encouraging criticality. Similarly, Mackenzie and Brown pursued the unfamiliar and unresolved. Their assemblage of textiles, organic matter, images, and sensory mediums indicated and encouraged what Jones called “thinking and making without knowing where one is going”. (1) The installation seemed to be fashioned in an improvisational manner, by reacting to materials and listening to the forms they would and would not hold.

Similarly, I as a viewer, was asked to let go of my rational and codified understanding of the collected materials and instead interpret how they might perform the uncanny aspects of a bog. Particularly, the exhibition called upon a type of ‘material intelligence’ which “implies not only human intelligence about matter, but the intelligence of matter, understood as adaptive and self-organising”. (2) Within both the visual and auditory works in the exhibition, the balance evoked between natural and unnatural, beauty and decay, and fascination and revulsion metaphorically echoed the duality and precariousness of the bog’s unrefined obscurity. Framing the bog as a space straddling extremes, as well as the work’s entrenchment in the metaphorical, both challenged structuralist ideas of truth and rationalism. As Jones maintains, passage into the unknown, not yet encoded, or unfamiliar “hints at an entirely different way of coming to know someone or something, involving an attunement of the senses to that which is other and irreducible to those frameworks”. (3) Brown and Mackenzie’s work demands the viewer let go of knowing and give time to feel, ruminate, and digest. The viewer becomes a component to the ecosystem, breaking down old material to produce something new.

Considering a more general context of this work, I can’t help but think of Vancouver as an urban space. Similar to a bog, Vancouver is a city distinguished by its dualities; it is a place of extreme wealth and poverty, of rising mountains and stretching seas, of industry and nature, and of a short colonial history and a long Indigenous one. Just as a bog is built on a bed of decay, the land has a history that is entrenched into the ground we stand on. But through the strange unworldly drone of the city, it is easy to ignore the duality of the land, and the complex history which lays beneath the concrete.

Veils of a Bog embraces the undetermined, suggesting there are more complex, transformative, and unsettled ways of thinking. The shifting duality of the bog creates an incomprehensible diversity of meaning that asks to be examined without expectation. Vanessa Brown and Michelle Helene Mackenzie call for an attunement of the senses to confuse and challenge that which is already encoded. This proposition, although framed within the representation of a bog, can be expansively applied to examine our political and environmental landscape, particularly in many Canadian cities, where space has become a privileged and colonial commodity. Mackenzie and Brown ask as we move through the bustling city, that we pause and listen to the complexity of the land—how the trees whisper a history in the breeze, and faint crickets and croaks emerge from the shadows.

- Jones, Rachel. “On the Value of Not Knowing: Wonder, Beginning Again and Letting Be” On Not Knowing: How Artists Think. London: Black Dog Publishing (2013), 1.

- Jones. “On the Value of Not Knowing: Wonder, Beginning Again and Letting Be”, 2.

- ibid.

Veils of a Bog ran from September 14 – October 20th, 2018 at the Western Front in Vancouver.

Feature Image: Installation view of Veils of a Bog (2018). Photo by John Dean, courtesy of the Western Front.